ESOL shows unique academic perspective

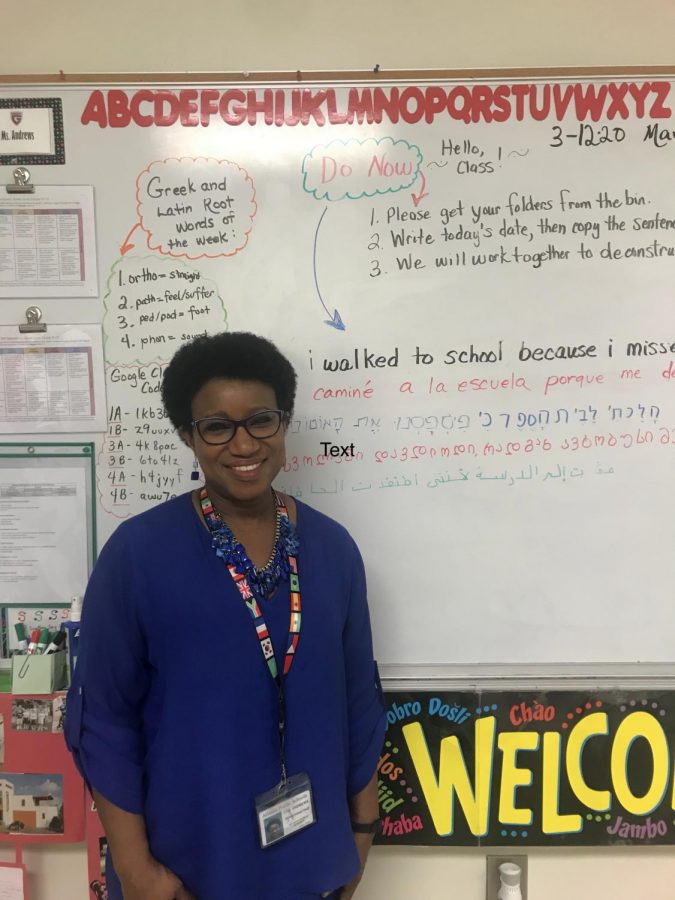

ESOL teacher Che Andrews displays the teaching methods she uses on her whiteboard. The “Do Now” consists of evaluating the sentence: “I walked to school because I missed the bus.”

March 24, 2020

“Why am I dumb? In my country, I was smart. All tens! Never even an eight! Now I’m here. They give me C’s or D’s or F’s — like fives.”

Che Andrews, an English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) Teacher, projects on the board a bilingual poem, “Why Am I Dumb?” by Jane Medina, for her 1A Oral Communications class. Junior Kerlyn Sanchez speaks up after a classmate recites the poem.

“That’s me,” Sanchez, a native of Guatemala, says.

ESOL students like Sanchez come from all parts of the language spectrum. Andrews teaches her classes, where students may have different understanding levels of English, with adaptive techniques.

At the beginning of class, Andrews writes, “I walked to school because I missed the bus,” then writes its equivalent translation in Spanish, Hebrew, Georgian, and Arabic. For the Monday activity, the students are tasked with identifying the parts of speech of each word.

The word “because” is unfamiliar to the three students in the class. Andrews rifles through a Spanish to English dictionary, attempting to find equivalent words in the students’ native language.

The language barrier proves to be challenging for students developing their English. Andrews believes that barrier leads to a common misconception about her students: that they lack intelligence.

“You have to be really smart to be able to code switch,” Andrews said. “I can imagine in their home countries they were getting all these great grades, and now it’s ‘you’re not that smart’, but they’re still smart.”

The gateway between ESOL classes and a fully-English course schedule for a student is the Georgia-mandated “ACCESS” standardized test. Andrews doubts that most native English speakers could pass the test, which consists of reading, writing, speaking and listening.

The test has five levels, with five representing a high and one representing a low English proficiency. Students can graduate the ESOL program, allowing them not to take any more ESOL courses, once they achieve a score of five. Andrews’ students took the test, which has four sections, from mid-January until March 6.

“We’ll see in May,” Andrews said. “I think some of them are going to exit, I can just tell by the way they worked.”

Standardized testing also proved a burden this year to ESOL students due to a lack of accommodations on the schoolwide Standardized Aptitude Test (SAT). For unknown reasons, ESOL juniors had to take the SAT with no time allotments or dictionaries. Accommodations can be provided to non-native English speakers so that they are given more time or a translation guide without definitions.

“This year, we’re starting to get accommodations for next year,” Andrews said. “I’m glad they’re juniors, because they can take it again next year.”

Coursework for ESOL classes tends to coordinate with regular courses. For example, Andrews’ 10th grade World Literature class is reading William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, although it is adapted to a slightly simplified English version.

In her first year teaching at Grady, Andrews has learned how to empathize with the plights of her students, who may have just arrived in America that year.

“Their determination, drive, perseverance — I love that about them; they just amaze me, how courageous they are,” Andrews said. “I try to be empathetic and put myself in their shoes.”

![DAINTY DESIGN: When junior and designer Anastasia Varenberg (left) approached junior Ella Thornbury (right) for modeling, Thornbury knew she had to accept.

“Shes my best friend in the whole world, so obviously, I had to say yes,” Thornbury said.

In return, Varenberg created an intricate dress fitted specifically for Thornbury.

“I was trying to go architectural with a lot of these like leaves,” Varenberg said. “I also made a cool little thing where [the dress] folds over. It looks kind of flowery and dainty and reminds me of Vivian Westwood a little bit.”](https://thesoutherneronline.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/7uFXgisNPpbs0YzppQvM8sHxcO6QpPrspyp78wuV-600x420.jpg)