Teachers conflicted over reopening plans, work to adapt

As the fraction of students who opted to return to in -person learning are phased in, most Atlanta Public Schools teachers are back in school buildings and have mixed feelings about the decisions being made, concerning reopening schools.

February 15, 2021

After an almost year-long community debate over Atlanta Public Schools’ reopening plan, magnified by a billboard, numerous protests and Facebook groups, students are returning to the classroom.

For the families who chose in-person learning, students in pre-Kindergarten through second grade went back to school on Jan. 25 and some special education students also returned. Those in grades 3 through 5 returned on Feb. 8. Those in grades 6 through 12 are scheduled to be phased in on Feb. 16.

“[Returning] is cost-benefit analysis,” writing and forensics teacher Mario Herrera said. “We don’t know what the costs are for the district. We don’t know what the benefits are for the district.”

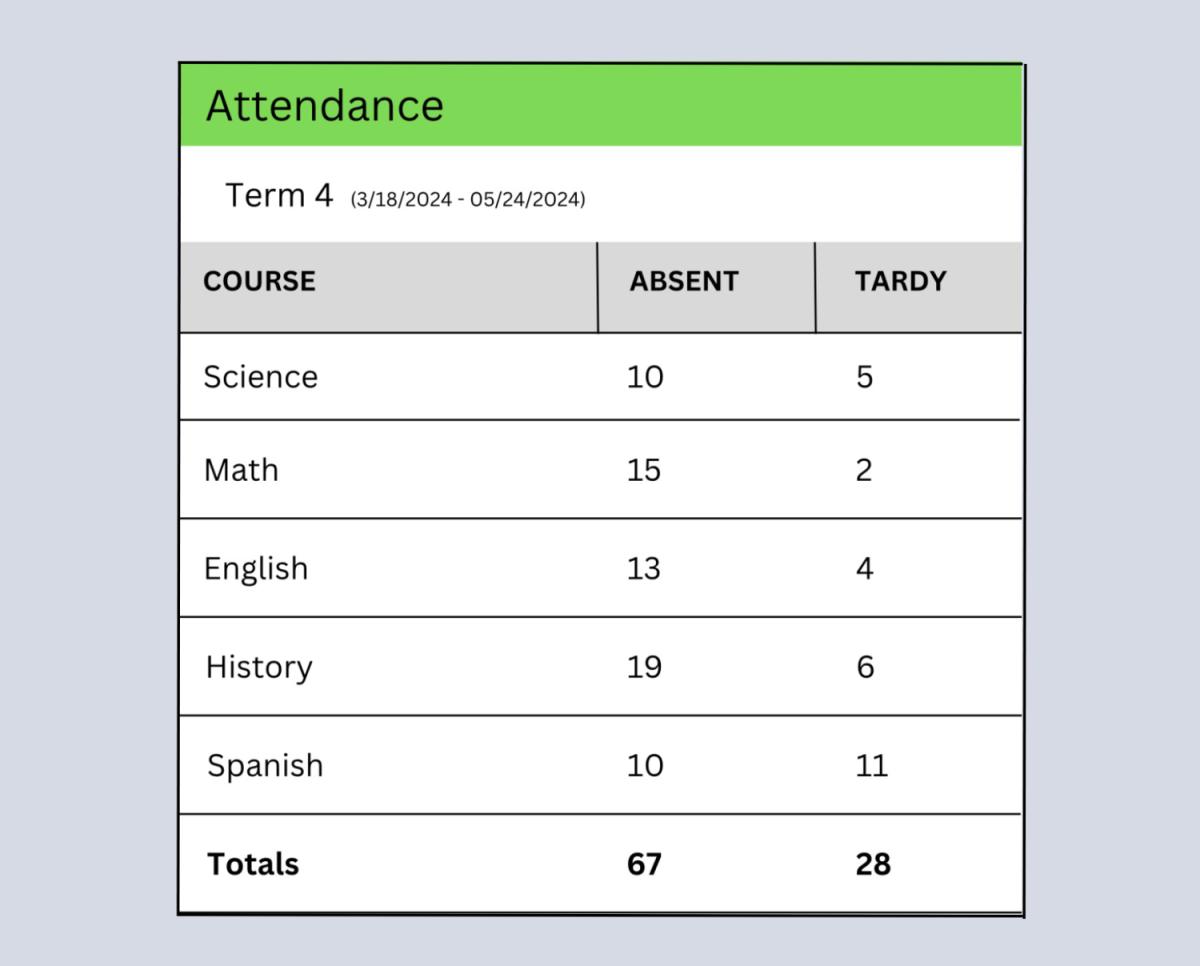

According to APS Board Chair Jason Esteves, there are a couple of students who are “constantly absent or very disengaged” in almost every classroom across the district. Despite teachers’ best efforts to educate students virtually, the decision to reopen was largely due to the effects of virtual learning on students’ academic and mental health, disproportionately affecting students of color.

“I want to give a shoutout to our teachers and our staff for all that they have done in this pandemic because they’ve done an extraordinary job to engage students and to teach them in a virtual setting,” Esteves said. “But, for some students, that is just not enough. And really, the decision to reopen buildings was based on the fact that there had to be an outlet for those students.”

However, Esteves also says that, while some of the students planning to return are those who have been the most negatively impacted by virtual learning, there are a significant number of people coming back to school who were not struggling.

AP American Literature teacher Susan Barber believes that there is a better strategy to prioritize safety and equity. She has consistently urged APS to give teachers the option to volunteer to return in-person and teach a select group of students who have been most negatively impacted by virtual learning.

“I am a huge advocate in this [model] for teachers to have choice like students have choice,” Barber said. “It just seems like that’s a better solution to … keep up with who’s in contact with whom and to mitigate the virus.”

Esteves says that while a plan similar to this was originally considered by the administration, it ultimately was not implemented for legal reasons.

For staff members who have a “legitimate need” to not be in the school building, the district offered staff the ability to apply for a telework arrangement. Requirements for being approved for telework arrangements include situations such as Covid symptoms or diagnosis, “a bona fide need to care for an individual subject to quarantine” or conditions where they are “at high risk for Covid infection per CDC guidance.”

However, some teachers feel that these conditions exclude a lot of teachers and staff that would have preferred to continue teleworking.

“A lot of teachers were denied telework because they didn’t have a note from their doctor,” Barber said. “But, we have teachers who have elderly parents living with them who are not vaccinated yet, and they’re concerned about bringing the virus home. [There] are different extenuating circumstances that maybe a doctor’s note doesn’t cover.”

Civics and government teacher Christopher Rhodenbaugh says he believes this is one of the main reasons teachers have criticized the reopening plan.

“The telework requirements are very steep, and many people who wanted to telework did not get the option to do so, which is part of why the resistance to this has been so loud,” Rhodenbaugh said. “We’re talking about people’s livelihoods.”

APS Superintendent Dr. Lisa Herring detailed the district’s rationale behind the requirements for teleworking.

“Our intent behind that was to accommodate all of those who needed to have special circumstances considered, compromised health systems or otherwise,” Dr. Herring said. “For the vast majority of our teachers or staff members, we were able to do that as long as they met the timeline, and we have extended and worked with that timeline in several iterations. But, I will have to own that there are always different circumstances to do that type of process that create unique scenarios. And we’ve had to, with our human resources department, work through that.”

Economics teacher John Cowan is anxious about contracting the coronavirus while teaching students in-person.

“Myself and many other teachers, I mean, we have bills to pay and love the job otherwise; so, it’s not to the point where it’s like, ‘Well, I’m leaving (my job),’ but it’s certainly anxiety,” Cowan said.

Adapting from the building

Since Jan. 19, teachers have been required to teach virtually from inside the school building.

“Even on a normal summer to fall transition, our teachers all come back several days before our students do to get ready for them,” school board member Cynthia Briscoe Brown said. “In this case, also, to work out the glitches before the students get there, to see what works and what doesn’t when we have more flexibility to change things around.”

However, due to concerns about health risks, going back into the building caused mixed feelings among teachers who were happy to see their colleagues but worried about jeopardizing their safety and the safety of students who would return in the coming weeks.

“I’m really conflicted because it’s been so great to see my colleagues,” Barber said. “Working in isolation is really difficult for teachers, so seeing my colleagues is great, but I’m also conflicted because … it is just not the right time to have people in the building.”

However, teachers have been using the time in the building to figure out how they will adapt their teaching styles and classrooms given the Covid-19 restrictions.

Cowan will have approximately six students in each of his three classes. He is planning on arranging desks six feet apart in a grid with surge protectors accessible for students to charge their computers, as class will still take place on Zoom.

“The classroom’s only so big; so, there’s only so many places you can put people and desks and things like that,” Cowan said.

AP Human Geography teacher Chris Wharton, who teaches freshmen, will have an average of 11 students in-person per class. Freshmen constitute the largest percentage of high school students going back in the school building. Wharton explained his hypothesis for this phenomenon.

“It’s just an impression that [with] my younger students being at home and the younger students not being quite as mature, maybe they need a little more structure, a little more supervision,” Wharton said. “[There is] a little more concern about parents leaving their kids at home when they’re younger.

In order to space out his students’ desks to comply with safe distancing measures, Wharton had to relocate to a larger classroom. The desks will be spaced out, six feet apart, alongside the classroom’s walls. Students will have their computers in front of them, listening to Wharton’s instruction through a Zoom call.

“When they breathe, they’re facing towards the wall,” Wharton said. “It’s sort of like when I’ve gone to a gym locally, they have all of the cardio equipment facing the wall [so people are] breathing at the wall rather than at other people.”

English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) teacher Che Andrews will have seven of her 33 students returning to her classroom physically. With a maximum of three students in one class, she has set up one long table in the center of her classroom for students to sit at least six feet apart from each other.

Andrews has found that her students have had trouble acclimating to a virtual environment when they are accustomed to hands-on, individualized lessons.

“We’ll usually (before Covid) sit at the back table and work together; it’s just not the same,” Andrews said. “It’s very difficult. Some of my kids have trouble manipulating the virtual world, especially the ones that are pretty new to the country.”

In a class where students are learning how to speak English through Andrews’s verbal instruction, being able to hear and speak clearly are essential elements of day-to-day learning. Andrews believes that because she will be teaching her students online and in-person with a mask on, her students will have difficulties hearing her instruction clearly.

“When you wear a mask, your voice is kind of muffled, and, with my students, I need to really speak clearly,” Andrews said. “And I’m concerned that I might not be able to communicate as effectively with my mask on, trying to communicate with my students at home and students at school, as well.”

However, Grady’s administration has offered a solution to her issue.

“The school said that they will provide us with a voice amplifier, so we’ll see,” Andrews said.

The district is providing personal protective equipment (PPE) to teachers, but principals have the flexibility and jurisdiction over how to distribute it and can also request specific equipment to fit their school’s needs, according to Brown.

Dr. Herring does not foresee any issues with the availability of PPE for schools.

“In addition to the funding that we’ve received from the Cares Act, the generosity of partners and philanthropic individuals across the City of Atlanta has been amazing,” Dr. Herring said. “And so, in places where we are already focused on our ability to resource, we’ve had an abundance of support from other partners as well to make certain that, whether it’s a select group of schools or throughout our system at large, we have more than enough.”

District disconnect

Since the beginning of the 2020-2021 school year, plans to reopen APS schools have been frequently altered. Originally, students who opted to return to in-person learning were scheduled to go back to school in October and November. However, due to a spike in coronavirus cases, the reopening was delayed. On Dec. 4, Dr. Herring announced her decision for a January reopening date. On Jan. 8, she announced a delay in the return for grades three through five and six through 12.

Some teachers feel that, despite the district’s efforts, communication to the teachers is lacking.

“From a political standpoint, it’s really frustrating that nobody seems to really want to be accountable for this, and the communication policy reflects that,” Rhodenbaugh said. “Many colleagues of mine reached out to board members and didn’t hear anything back for a significant amount of time. There have been improvements since January, particularly from some members of the school board, but there is a long way to go to restore trust.”

Herrera shares Rhodenbaugh’s concerns about the lack of transparency.

“I see some parallels between the lack of a strategy that we’ve had nationally; that kind of feels like what’s happening at the district level,” Herrera said. “Now that could be because of the state. I have no idea. So it’s hard for me to get angry at everyone because I don’t think anyone is holding back information on purpose. I don’t think that anyone is making decisions to harm others. I don’t believe that at all. Tell us your process.”

Board chairman Esteves is aware of teachers’ concerns regarding communication and believes that in a time of urgency, such as the pandemic, the district needs to “over-communicate rather than under-communicate.”

“I certainly hear that frustration and empathize with it,” Esteves said. “I do think that as an administration, as a leadership team, the district needs to communicate better with all of our stakeholders, including teachers. So, as a board member and as a board, we are certainly providing that feedback to the administration.”

Dr. Herring detailed her methods of receiving feedback from staff.

“I’ve had situations where we’ve had to talk with school leadership around ensuring that the practices and protocols that we expect to be in place are fully implemented and that if teachers give us a different insight to that, we can appropriately adjust,” Dr. Herring said. “I have a teacher advisory group that I do meet with regularly and just recently met with them last week and was able to secure a lot of feedback around what is working, and again, what is an area of concern.”

Herrera and other teachers are confused by what data APS is using to determine whether schools should reopen.

Esteves explains that the metric used to make decisions about reopening has changed since August.

Originally, APS was relying primarily on the number of cases per 100,000 people. However, as Esteves explained, it became apparent in late December that community spread was not going to drop below “moderate spread” until at least the spring; so, now, APS is relying primarily on the ability to implement mitigation strategies, which studies have shown lower the risk of spread in schools.

Board member Cynthia Briscoe Brown said the measures for reopening have changed because of the additional measures the district has taken to improve safety. These include the implementation of weekly voluntary surveillance testing, upgrading of HVAC systems to improve air circulation and a mask mandate.

“I think when we were starting last fall, we were depending heavily on the number of cases per 100,000 people as our primary measure of when we thought it would be safe to return to the in-person,” Brown said. “As we have learned more about how this virus operates and we have learned more about how to minimize exposure and minimize risk, other factors have become more important.”

APS is partnering with Viral Solutions, a coronavirus medical team, to test students whose parents consented or consenting adults weekly. Within 24 hours, individuals will be notified of any “clinically-significant reading” before they re-enter the school building, according to Dr. Herring.

“I can tell you that, without question, every week when I see the report back on how many people have been tested and how many are coming back positive and if there are any concerns and a high number that come back negative, it’s a great resource and data-driven factor to help them mitigate well,” Dr. Herring.

Dr. Herring encourages students and staff to participate in the surveillance testing, “so that they can be a part of the frequency of weekly Covid testing for the entire population that choose to be face-to-face.”

Herrera recognizes that the district is making an effort to ensure teachers and students stay safe but still believes that everyone is not on the same page.

“There are some remarkable people all over Grady and all over the district,” Herrera said. “Dr. Sims (Dr. Dan Sims, APS Associate Superintendent of Schools) came to Grady … to make sure everything was okay. The district is trying. What frustrates me is that critical thinking and that type of discussion and discourse is not happening. We need to make decisions in ways that show that you can have a disagreement and still come to a consensus and make things work as best you can, and I just don’t think we’re there yet.”

Despite his concerns, Rhodenbaugh recognizes the tension between the administration at the district level and the teachers at the school level is not a comfortable one and says it “does not feel good to be in opposition.”

“These are people I agree with about how the world should look,” Rhodenbaugh said. “It’s just such a weird place to be, to feel this level of conflict like within the organization. This is what Covid is doing in all sorts of places, and everywhere it’s just, unfortunately, dividing us.”

Brown said navigating reopening during the pandemic has been a series of “impossible answers to impossible questions.”

“Even though we as board members don’t actually make these decisions, I feel personally responsible for every child and every employee,” Brown said. “And [I] want to do the best that I can, for everyone else, and just balancing all different interests and factors is very, very difficult. But, I think we’re gonna be okay.”

Staff solidarity

Despite some teachers’ frustrations over the lack of transparency with the district administration, the Grady administration has been lauded for its receptiveness.

Economics teacher John Cowan is thankful for the Grady administration’s efforts to be cognizant of teachers’ concerns.

“I would say that Dr. Bockman and the Grady administration have been very receptive and understanding of teachers expressing their fears and anxieties,” Cowan said.

Cowan recounted that, during a recent faculty meeting, one administrator encouraged teachers to not be afraid to openly express their hesitancy and concerns.

“[The administrators] do not want you to feel like you can’t say these things just because they may conflict with what district administration is pushing,” Cowan said. “We were being told, ‘You can voice your concerns here, and you’re not going to face repercussions just because you’re afraid of the virus.'”

Andrews agrees and believes that the school administrators are “top-notch.”

“They have been very, very cooperative and open to everything,” Andrews said. “They’re just very considerate of teachers, and I’ve been teaching a while and I’ve been to different places, and I recognize it.”

Rhodenbaugh believes teachers “are in solidarity with our school administrators” and empathizes with the position of the Grady administration.

“I feel so badly for [school administrators], that they are standing in the middle of an intersection between parents and families, teachers and the district,” Rhodenbaugh said. “And they’re pulled in every single direction.”

Andrews detailed that, although there is a space for teachers to voice their concerns to administrators, teachers also are also able to relay their situations and anxieties to each other in conversation.

“We talk about our concerns, and we try to help each other and encourage each other, and I just love the staff,” Andrews said. “I love my fellow teachers, we just uplift each other.”