‘It had to be addressed:’ Second impeachment permeates classrooms

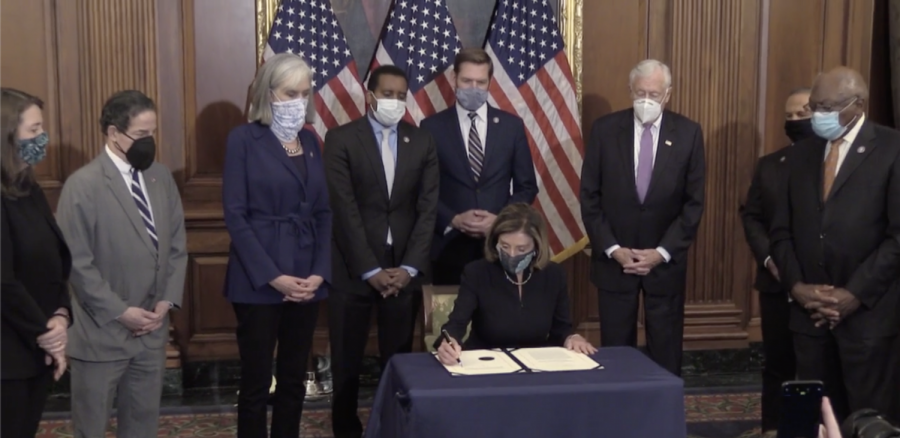

Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi signs the Articles of Impeachment against President Donald Trump after its passage in the House of Representatives on Jan. 13, 2021. The President was impeached for the second time during his first and only term for inciting an insurrection of the US Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

January 21, 2021

On Jan. 6, 2021, fueled by misinformation about election fraud, a violent mob breached the U.S. Capitol for the first time since 1814, temporarily interrupting the congressional certification of Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 Presidential election.

Across the globe, millions sat glued to their TV screens, Twitter feeds and computers as the world watched images of representatives in gas masks, insurrectionists battling with police and radio silence from the president. The Capitol Police and national guard eventually cleared the Capitol but not before the events of Jan. 6 left five Americans dead and a nation rattled to its core. The Grady community was no different.

“On Jan. 6, my initial reaction was disbelief, which later turned into heartbreak, fear and absolute rage,” senior Lucia Fernandez said.

For both students and faculty, the events of Jan. 6 added to the existing pressure of virtual learning. Jan. 6 was just nine days from the end of the first semester, with final exams set for Jan. 14 and 15 and the next semester starting Jan. 19. While the day did not interrupt instruction, as it was an asynchronous instructional day, the Grady community had to move on to regularly scheduled instruction, uncertain about what the country would look like when they woke up the next morning.

“I went to bed that night worried,” AP Calculus teacher Andrew Nichols said. “Worried about our country, but also worried about my students. I knew they would be shaken just as I was. I knew it had to be addressed.”

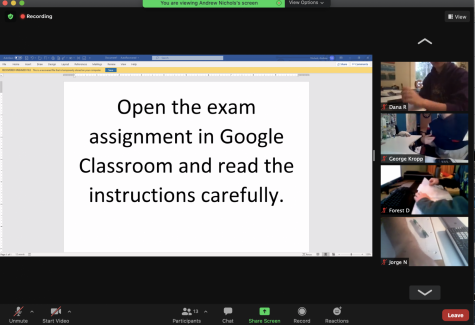

Nichols remembers having to administer an exam to his AP Calculus BC class on Jan. 7, unable to move the test day due to the time constraints on the end of the semester.

“I gave an exam to one class that day,” Nichols said. “I considered postponing or eliminating the exam, but I decided not to do so. A combination of time constraints and grading policies made that impossible. We had to forge ahead. Ultimately, I was proud of my students for the strength they exhibited. In other classes, we were able to take a few minutes to acknowledge the events of the previous day and have a short discussion. My students expressed concern, but also a need to stay focused on the upcoming exams.”

The days that followed only created more uncertainty for students. President Trump was banned from his social media accounts, the House of Representatives passed articles of impeachment for the second time and Inauguration Day remained less than a week away.

Following the passage of an impeachment resolution in the House of Representatives, President Trump became the first president to ever be impeached twice, the first time occurring in December 2019.. Much has changed for Grady students between the two impeachments (students were in-person during the first), but many are drawing comparisons to the first impeachment of President Trump.

Senior Andrew Bradshaw, who opposed impeachment in 2019, sees the difference in severity between the actions leading up to impeachment while still opposing the current measure.

“I would say that I’m definitely more understanding of the second impeachment only because it led to violence,” Bradshaw said. “That being said, I still don’t agree with it. The Article of Impeachment claims that [President Trump] ‘incited an insurrection’ but, from what I’ve seen, nothing Trump did meets the legal requirements of inciting an insurrection, granted impeachment is not technically a legal process.”

On the other side, Fernandez supported both impeachment resolutions but acknowledges that, while she believes in both instances the president committed impeachable offenses, there are different priorities this time.

“Some people may view this impeachment as unnecessary because his time in office is almost over, but I find it incredibly necessary because of what comes after his presidency if he’s not impeached,” Fernandez said prior to Trump leaving office Jan. 20.

While students are facing the unprecedented task of being a high school student during both a pandemic and constitutional crisis, the events since Jan. 6 are forcing many teachers to reckon with a decades-long debate on discussing personal political beliefs in classrooms.

Chris Rhodenbaugh, who teaches both U.S. Government/Civics and AP Comparative Government, believes that, especially in social studies, teachers must walk the fine line between their personal experiences as a teaching tool and advocating for a certain ideal.

“I think it is really important that my students see me as a person and as a human being who is struggling to understand the world and what is happening so I cannot strip all emotion out of my class and instruction because then I am not modeling the challenges of being a thoughtful and concerned citizen at a time like this,” Rhodenbaugh said. “So many of the norms that I studied and built my career upon are being challenged, and I have to acknowledge to some extent what that feels like but I also have to be really mindful and careful to not be really reactionary in my tone and to be purposeful when I am sharing my own opinion and perspective.”

While personal political beliefs may be the norm in social studies classes, they aren’t typically brought up in other classes. However, with the influx of instability following the violent insurrection and impeachment, even teachers who don’t focus on politics are taking on a new role in facilitating discussion.

“Yes, we’ve talked about current events in my math classes,” Nichols said. “But we stay focused on how we manage our stress and the mathematics we have before us. I don’t see politics as a subject that should be avoided. As long as the teacher creates a safe, unbiased environment for discussion, we can talk about difficult topics.”

As with many terrible events, the recent loss of life and insurrection at the Capitol also brought a newfound understanding of U.S. politics in class, especially for those taking U.S. Government/Civics, a course required to graduate high school.

“I think that I have been able to find ways to ensure that the madness of what is going on is routed back into my government classes,” Rhodenbaugh said. “Understanding that the constitution is the supreme law of the land and understanding extreme concepts, such as rule of law or an independent judiciary, separation of power or federalism, a lot of difficult things to teach in American government class; more abstract concepts are being more real.”