Homeless students face setbacks, staff shows support

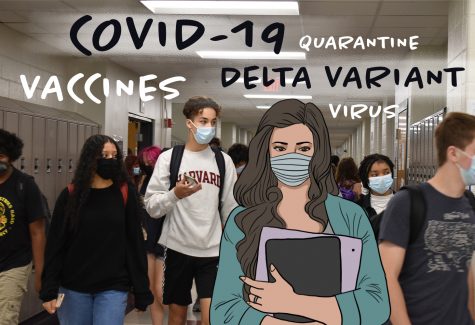

Graphic by Olivia Podber

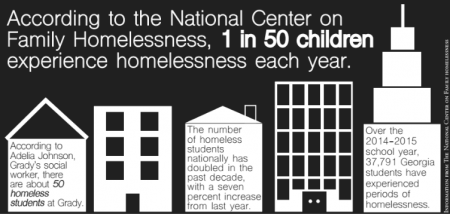

Walking around the hallways of Grady, it is not unusual to see some groups of students wearing varsity football gear, textbooks in tow, and others speaking to each other in different languages. The students that travel through Grady’s halls are renowned for their individuality, each one noticeable in their own way. An overlooked group at the school, however, are the school’s approximately 50 homeless students.

“When people think you are going home, you don’t know where you’re going to sleep, you don’t know where you’re going to stay, [or] even if you’re going to eat,” freshman Asha Carter said. “Those are the things I have to deal with every single day.”

Since she moved in with her father in April, Carter has been homeless, constantly moving between shelters, hotels and rentals, and often sleeps in his van. Because of her dad’s time in prison, it has been difficult for them to find shelters that will accept them or for him to get a sustainable job. To earn income for herself and father, Carter often sells chips, candy, or water which earn more money than his weekend security job.

As a homeless student, getting to school on time has been a challenge and sometimes even impossible for Carter. To get to school, she often has to collect enough money for Marta and after multiple stops, may even have to run to class. On some days, Carter has been unable to get to school if she cannot arrange transportation. When she does arrive, it is often late.

““Most of my teachers just assume I’m being late,” Carter said. “They don’t really understand why. They just think it’s a teenager making excuses.”

Even though some students enroll as homeless, teachers are not always aware. Usually, teachers find out which are homeless if an issue such as tardiness comes up, prompting the school to notify the teacher.

Social Studies teacher Susan Salvesen has had a number of homeless students in her 11 years at Grady.

“Most of the time I find out through the students,” Salvesen said of students’ homeless status. “They come to me with an issue or a problem, and then as I’m trying to help them through it, they’ll reveal that they’re homeless.”

When students indicate they are homeless, Salvesen tries to help by giving extra time on assignments, trying to figure out what they need and filling out a social worker referral form.

“I wish students would come to us earlier when there’s something going on rather than later,” Salvesen said. “I think that if they just let us know, the teachers at Grady are, for the most part, are willing to work with students when they know that they’re under some sort of stressful situation.”

Although one teacher has been especially understanding of Carter’s circumstances, the majority of her teachers are unaware. During her classes, she often is frustrated because of issues outside of school. Carter has taken her anger out on her teachers, which she instantly regrets.

“If your teacher makes you feel a certain way and you feel uncomfortable, it’s going to be hard to go to them. If I feel comfortable, I’ll speak, but at the same time, if you notice that I’m good and then out of nowhere I’m just slowly going down, at least try to talk to me and maybe we can figure something out,” Carter said. “Then, I might speak up.”

Before a teacher realizes that a student is homeless, their performance in school can look concerning.

“A lot of times as a teacher you just think ‘oh, they’re not interested in my class’ or ‘they didn’t do their homework because they didn’t feel like doing it,’ when a lot of times, it’s an indication of something else going on,” Salvesen said.

School social worker Adelia Johnson is the most direct contact and source of help for homeless students. She keeps an open-door policy where any student can approach her for help.

“It is my role to make sure they have resources in place for anything that may impede on their education,” Johnson said. “I’ll arrange transportation or order them school supplies, coats or clothes. I keep food here [in my office], so they know they can always come by if they need to eat.”

When teachers suspect that a student may be homeless, they can contact Johnson, who will then reach out to the parent for permission to work with the student.

“Being at Grady has been phenomenal with regards to resources for students who may be in less favorable positions or situations,” Johnson said. “They have a very supportive staff, and even the students have shown great support. I have never seen anything like it.”

In the Grady community and Atlanta area, homelessness is a prevalent issue combated by schools and private organizations. Parent Karen Kelly works with homeless youth at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church.

“It’s a very hard population to serve,” Kelly said. “The kids have frequently been through a lot of trauma, either caused by stress just because they’re homeless or the trauma that caused them to be homeless in the first place.”

Kelly is a founding member of the Boyce L. Ansley School, a private non-profit school for homeless students located at St. Luke’s that aims to open in August 2018. She hopes the school will ease some of the many setbacks homeless students face.

“One of the challenges, if you’re homeless, is that you move around a lot,” Kelly said. “You might go to one school at one point of the year, and then, if you find someplace else, they might move to a second school. The kids get moved around a lot, which impacts their academic achievement.”

There are differing opinions as to what should be the first priority when helping the homeless. Kelly believes shelter is the primary need.

“The most important thing when you’re trying to solve homelessness is getting in housing first,” Kelly said. “I don’t think most people know that. They think you should get them a job, but if they don’t have someplace stable to stay, then the other pieces are pretty hard to put into place for families.”

While Johnson agrees that shelter is important, she first tries to provide “non-judgemental help” to homeless students.

“[Getting a homeless person a place to stay] is the most ideal thing, but that’s not always the quickest thing,” Johnson said. “I think [the first step is] just insuring that that student or that family is in a good mental place. Just letting them know that ‘hey I know this is your situation right now, but we’re going to work together to try to get something more stable, get you covered, and get you a roof.’”

At one point as a teenager, Johnson was homeless. Since then, she feels as though social work found her, and she has wanted to help others. She tries to give students hope and show them that their situation can improve.

“I often use the Harry Potter story because the author was homeless at one point,” Johnson. “I share with a lot of my students that may be dealing with homelessness that if she knew Harry Potter would be what it is today, I think she would be a lot happier being homeless. She had no idea, but she persevered and was resilient. I often use that as a key to hope just to let them know that this is your current situation, yes, but it won’t always be your situation.”

Hi I'm Max Nevins and I'm the Lifestsyle Associate Managing Editor. This is my second year writing for The Southerner and last year I was a Junior Online...

![DAINTY DESIGN: When junior and designer Anastasia Varenberg (left) approached junior Ella Thornbury (right) for modeling, Thornbury knew she had to accept.

“Shes my best friend in the whole world, so obviously, I had to say yes,” Thornbury said.

In return, Varenberg created an intricate dress fitted specifically for Thornbury.

“I was trying to go architectural with a lot of these like leaves,” Varenberg said. “I also made a cool little thing where [the dress] folds over. It looks kind of flowery and dainty and reminds me of Vivian Westwood a little bit.”](https://thesoutherneronline.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/7uFXgisNPpbs0YzppQvM8sHxcO6QpPrspyp78wuV-600x420.jpg)