District adopts divisive concepts complaint resolution process

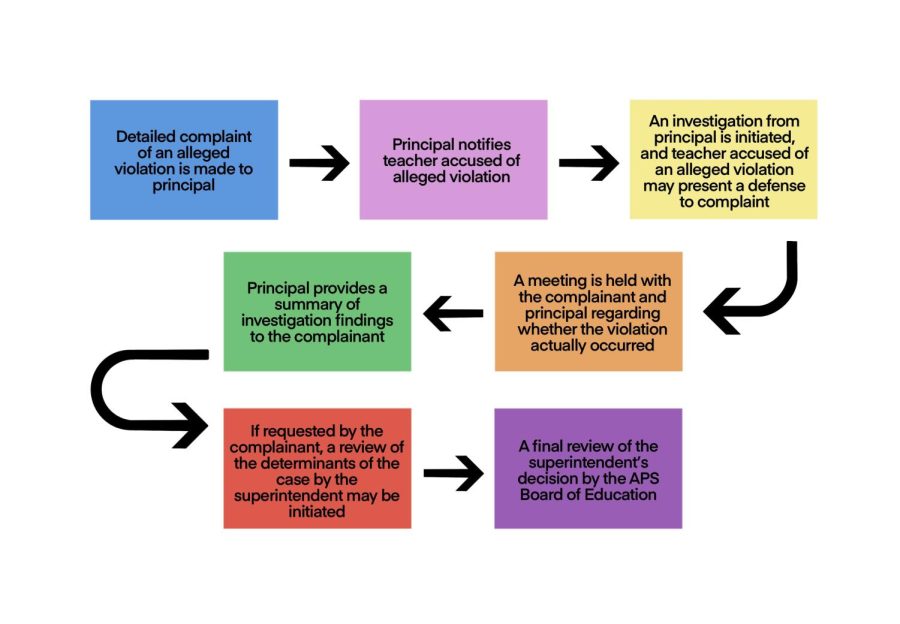

In the complaint resolution process, a complaint of an alleged violation of HB1084 is made to a school principal, the principal investigates and informs the teacher of the violation, a meeting takes place between the principal and the person filing the complaint and a possible appeals process takes place.

December 5, 2022

The Atlanta Board of Education finalized a complaint resolution process for divisive concepts taught in schools and the district’s response to such complaints.

The complaint resolution process, Policy IKBB, is the board’s response to April’s House Bill 1084, which bars teachers from acting upon, promoting or encouraging divisive concepts, such as the inherent superiority of one race over another. In the presence of an alleged violation of HB1084, the bill requires school boards to provide a complaint resolution policy, process and appeals.

The process follows a general progression where a complaint of an alleged violation of HB1084 is made to a school principal, the principal investigates and informs the teacher of the violation and a meeting takes place between the person filing the complaint and principal to discuss whether or not a violation occurred. If requested by the complainant, an appeals process will involve the Superintendent Dr. Lisa Herring and the school board.

Board member Cynthia Briscoe Brown believes APS’ complaint resolution process aligns with the law while supporting the district’s educational values.

“It includes what we believe is the minimum necessary to satisfy the law, while also providing us the opportunity to affirm our long-standing commitment to supporting and encouraging instructors and students in teaching and learning about challenging issues and ideas,” Briscoe Brown said.

Briscoe Brown believes the policy reiterates the district’s values on the discussion of controversial issues.

“We reiterated our commitment that students and teachers have the right and the obligation to teach and learn controversial issues free from bias, prejudice or retaliation,” Briscoe Brown said. “We included the constitutional protection cited in the model language because they affirm our commitment to our instructors and our students’ rights.”

Under the bill, teachers may permit the discussion of divisive concepts, in addition to the curriculum of slavery and racial discrimination, but cannot center their curriculum on this and cannot provide their own opinion or endorse a viewpoint.

Social studies teacher James Sullivan said the exact language creates a gray area for interpretation.

“It’s kind of toothless because [divisive concepts] are something that never was an issue and never would have been an issue,” Sullivan said. “But, you can put it into legislation, and you make this language such that anybody who has an ideological axe to grind can just say, ‘You violate the law because I think you were putting your opinion into that.’ I think that [legislators] knew what they were doing in writing this legislation, but [violations] are just not really going to ever happen in any classroom that I’ve ever heard about.”

Junior Julian Ender believes that although divisive concepts are part of history, it is important for teachers to remain relatively neutral on politicized or divisive concepts.

“The goal of education in my eyes is not to teach somebody to think a way, but is to teach somebody how to form their own methods of thought and get their own takes on the world,” Ender said. “I agree with the notion that a teacher should never center their curriculum on something like racial superiority or that a teacher shouldn’t have a biased curriculum in their class, but for the most part, divisive concepts are fundamentally ingrained in the social sciences.”

Under the bill and APS’ new policy, parents and guardians, students who are at least 18 or are emancipated and employees can file complaints.

Ender does not like the decision to allow parents to file a complaint.

“The point of this [bill] is to prevent teachers from telling kids how to think, but by the time you’re 18, you are easily the most free-thinking students at that school,” Ender said. “I fully disagree with the notion that parents should be allowed to file the complaint because one of my greatest issues with any school board complaint is parents do not attend the school. They do not have an idea of what’s happening. They can hear something that’s been told to them from a really biased source, and that’s all they know about school.”

Sullivan agrees and believes excluding underage students was purposeful.

“Tell me why would you, if you’re one of these legislators writing the legislation, leave out the brains in the classroom from the process?” Sullivan said. “Who you really want to hear from is parents who have read something and think, ‘What’s my child being taught?’ They absolutely should have included students; what bigger stakeholder is there than a student of any age? If this is about stakeholders having a voice in what’s being taught in social studies classrooms, you’ve left out the most important stakeholders: the students.”

The complaint by students who are at least 18, parents, guardians or school employees begins the complaint resolution process which defines Policy IKBB. In terms of the resolution process, which follows many steps as mentioned, Ender believes that it is extensive, but has a problem with the fact that one person is in power of the case at two separate instances.

“I think my greatest issue with it is that there are two separate points where power lies in one person, and imagine if we just gave one person the power in [the House or Senate],” Ender said. “I think there should also be a school board for the review process made up of the principal, the vice principal and people who are just important to the administration of the school. They’re not making a whole permanent board thing here, but in my eyes, what would really remove a lot of bias is if you can cut out the superintendent of the area entirely and just go to this school board.”

During its October meeting, the board completed the first reading of Policy IKBB. Since then, two major provisions have been made to the process on behalf of input from the community. Due to these provisions, teachers and staff members accused of wrongdoing will now be notified of the complaint by the principal within a day, and they will be able to present a defense to the complaint during possible investigations.

“Since our last board meeting, we have specifically included due process protections for employees accused of violating the law because we believe that they should have all the rights afforded to them to defend themselves and to weigh in, including the calling of witnesses, the making of a statement and the reviewing of the complaint against them,” Briscoe Brown said.

Sullivan supports this decision and feels that it reflects how APS has been very proactive in creating a sound complaint process with fair treatment for all parties involved.

“APS had to step up and allow a teacher to say, ‘May I defend myself, because that’s not what happened?’” Sullivan said. “If that’s left out from the state legislation, the only thing the teacher can have is a complaint filed against them, and you’re talking about a teacher potentially losing their job over this. They should have a right to defense and to make their case. You’re not allowing the teacher to defend under the state legislation as written [without due process]; what you’re doing is leaving [the case] to forces outside the school building to make a decision and to decide to move this forward.”

Jones believes that input from the community has also developed the need for more specificity in the policy, which the APS administration headed in the form of regulatory (legality-related) practices.

“Some of the feedback we’ve gotten since our last meeting has touched on some of what Cynthia was saying, and some of it was also asking for a deeper level of specificity,” Jones said. “I think that’s the fine line between where you divide the work between a board policy and a regulation. There are some detailed parts that we let the administration go forward with, and if people want to have input on that, then please do send that in.”

Briscoe Brown believes that the policy review committee and her administration colleagues have put together the best possible policy which not only satisfies Georgia’s law, but also reiterates APS’ own educational mission. She hopes for more community input and notes the influence APS has had on other school districts through this policy.

“I think we’ve satisfied the state and we’ve also taken the opportunity to really affirm our values and our educational philosophy,” Briscoe Brown said. “We look forward to including some additional input in our regulations which will be more specific to the implementation of this policy. I’m excited to say that this [policy] has gotten some interest from other districts both within the state and across the country, and it always feels good to be a leader and a model for good work in other districts.”