Advocate and journalist Ida B. Wells is the right name for our school

Ida B. Wells is known for her investigative articles about the pervasive practice of lynching during the late 19th century. She also spent much of her life advocating against segregation and for women’s rights.

September 2, 2020

The Henry W. Grady Renaming Committee recently came to a consensus to recommend a name other than Grady to the Atlanta Board of Education. Therefore, community discourse has partially shifted towards what the new name ought to be. We as a school community are given a unique opportunity: we get to suggest a name that embodies the very spirit of our students and encourages the ideals we prioritize as a community. The Southerner recommends changing the name to Ida B. Wells High School because she personified the spirit of advocacy present within our community. Her life’s work in journalism honors our school’s outstanding reputation in communication, and she criticized the systems of oppression that Grady himself was a proponent of.

When Wells witnessed injustice, she did everything in her power to fight against it. The lynching of her friend, Thomas Moss, served as a catalyst for her anti-lynching advocacy. She wrote scathing editorials and investigative pieces chronicling and criticizing the widespread practice of lynching. Wells wrote and disseminated her pamphlet, “A Red Record,” to share lynching statistics with the public and organized a protest in 1898 in Washington D.C. to demand reforms from President William McKinley’s administration. Not only did she become a renowned leader of the anti-lynching campaign, but she also was a key founder of many civil and women’s rights organizations: the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the National Association of Colored Women and the Alpha Suffrage Club. Wells was an active voice in the fight for women’s suffrage, and the work of the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago is credited as a significant reason why Illinois passed the Equal Suffrage Act.

Wells’ dedication to fighting for social justice encapsulates the essence of the ideals Grady’s student body cares about. We are a school full of activists, with students organizing their own Black Lives Matter protest, registering students to vote and establishing clubs such as March For Our Lives to discuss issues facing our generation. Past generations of Grady High School students had that same passion for advocacy. What better way to honor that passion than to choose to name our school after someone who spent her entire life fighting against injustice?

Additionally, Wells was known for her exceptional journalism, becoming the most prominent Black female journalist of the time. She became owner of The Memphis Free Speech and Headlight (which eventually became The Memphis Free Speech) and used her platform to criticize the conditions of Black-only schools and the horrors of lynching. The editorial she wrote about the lynching of her three friends was so brutally honest and scathing that a White mob angrily destroyed the office of The Memphis Free Speech and Headlight.

Although she had to leave Memphis for her own safety, the fear tactics used against her did not stop her from using the press to highlight the prevalence and brutal nature of lynching. She wrote and led some of the most influential newspapers of the time including, The New York Age, The Chicago Defender and The Conservator. In fact, famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass himself was in awe of Wells’ coverage of lynching, writing, “Let me give you thanks for your faithful paper on the lynch abomination now generally practiced against colored people in the South. There has been no word equal to it in convincing power…Brave woman! You have done your people and mine a service which can neither be weighed nor measured.” This kind of glowing endorsement from such an influential man in the fight for racial justice speaks to Wells’ character and the quality of her journalism.

Our school has a rich history of strong journalism and communication programs. The Boys High School newspaper, the Tatler, was Georgia’s top high school newspaper for two years while the Class of 1931 attended the school. That standard of excellence in journalism continued. Our school newspaper, The Southerner, has been covering the school community since 1947. From 1981 to 2011, Grady served as the district’s communications magnet, drawing in students across Atlanta Public Schools who had an interest in journalism among other branches of communications. Naming our school after Wells continues to honor our school’s strength in communications; she inspires courageous, truth-telling reporting in a way that no other historical figure can.

Some community members who are opposed to naming the school after Wells have noted that she lacks the same personal connection to Atlanta as some of the other name candidates. Part of the reason she didn’t have as much presence in the South later in her life was because White supremacists actively sent her death threats if she were to live in the South because of her lynching stories. That being said, she still had deep roots in the South since she grew up in Mississippi, and in Atlanta, we witness the impacts of her advocacy every day. We believe that the connection of her character and life’s work to the ideals of our student body is more important than a direct connection to our geographic location.

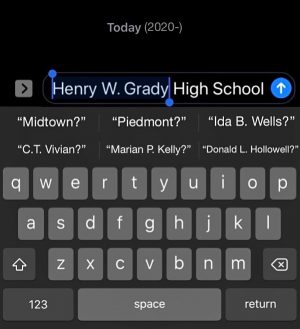

Additionally, some people support the idea of moving away from naming the school after a person, instead opting for a place, such as Midtown or Piedmont High School, or concept, such as Freedom or Beloved Community High School. There is a valid concern that no historical figure is perfect and flaws are inevitable. However, we have the ability to use our 21st century lens and all relevant historical accounts to vet possible candidates and ensure that their positives outweigh their negatives. Wells was anti-racist in a time when our current namesake was the opposite. Even within the context of the time, she passes with flying colors. Moreover, naming the school after a place doesn’t automatically include the entire student body. Geographic locations aren’t neutral; places have racial history as well. Naming the school after only a single neighborhood or location within the cluster excludes the rest of the student body. Also, some have suggested naming the school after a concept instead of a person or place. Some might say that names denoting positive ideals serve as a goal for students to aspire to as well as a nod to past advocates, but these names could also imply that we have reached the sought after ideal and are past the need for racial healing. Our school community has a long way to go before eradicating the ideas of White supremacy; changing the name is just the first step. Students can find the inspiration to continue the fight against injustice from a strong lifelong advocate, Ida B. Wells.