New attendance policies increase punctuality

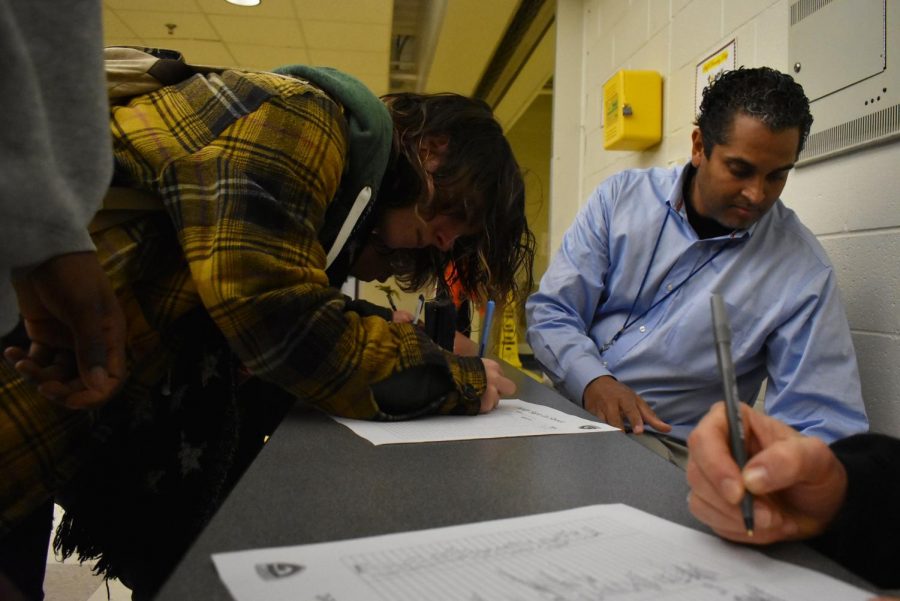

Administrators such as Byron Barnes help issue tardy slips to late students.

November 20, 2018

Student attendance, at this time a year ago, was 95.3 percent and has now increased to 96 percent as the administration has made attendance rates a priority.

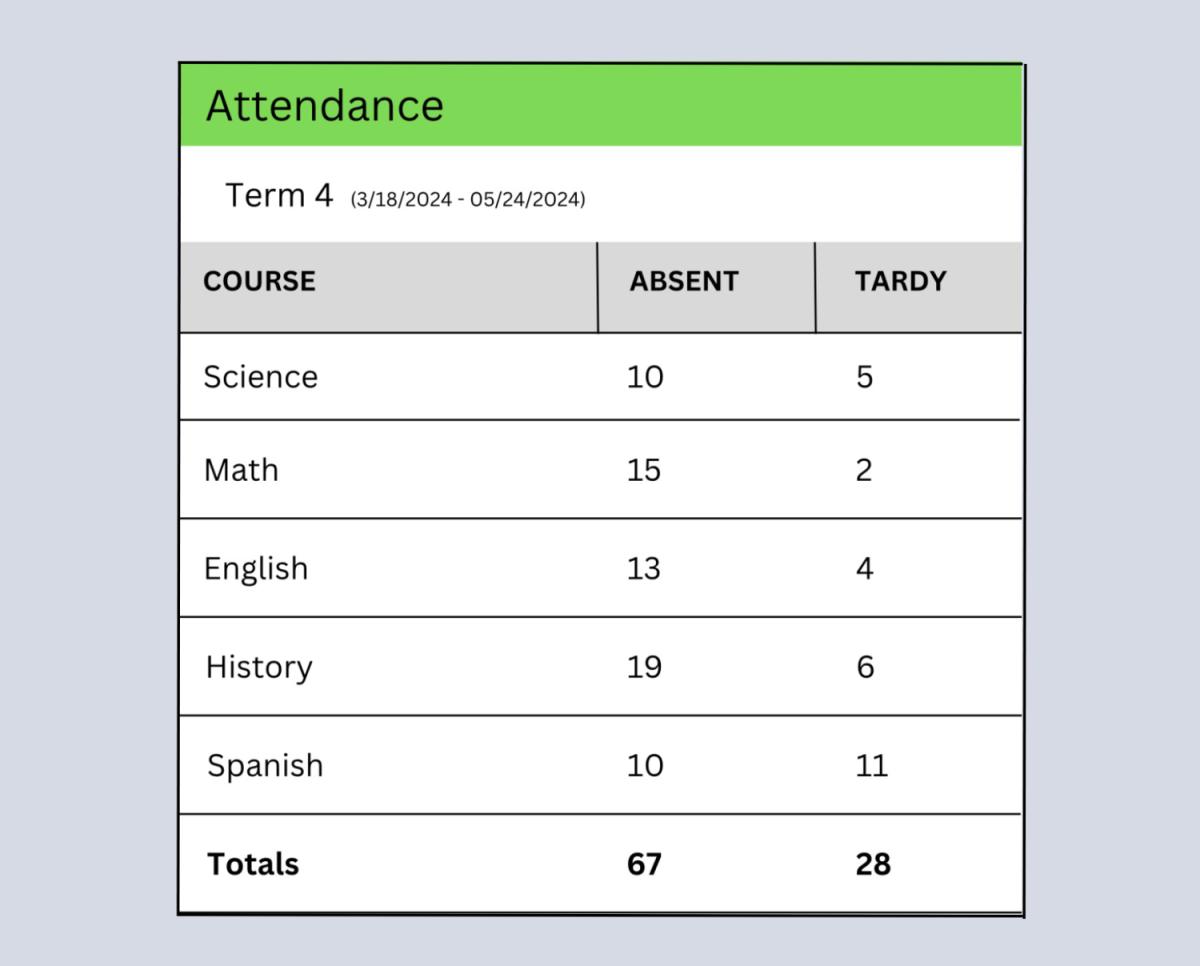

Last school year, Grady’s student tardies totaled close to 20,000, with approximately 15,000 tallied during first period. This year, the staff started strict attendance enforcement early in the year in an attempt to decrease first-period tardies.

“I’ve heard more this year from teachers about first period tardiness,” Principal Dr. Betsy Bockman said. “It’s a burden on the teachers to have to keep up with kids that are late and missing work, but first period tardies are disruptive to the rhythm of the class and instruction.”

Chronic absence, when a student misses at least 10 percent of school days due to any type of absence, is a nation-wide issue. 20 percent of U.S. public high school students were chronically absent in the 2013-2014 school year. 17.8 percent of Grady students were chronically absent during this year, and this rate decreased slightly in 2015 to 17.2 percent. While Grady’s chronic attendance is lower than the national average, Atlanta Public Schools’ (APS’) rate of 17 percent in 2013 for all their school was far worse than the national average of 13 percent, and it further increased to 20 percent in 2015, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s Civil Rights Data Collection.

APS is aware of the issue and is trying to improve attendance with their initiation of new strategies: encouraging schools to create attendance teams; training administrators on attendance protocol; establishing an audit protocol; messaging families, according to the APS Office of Communications.

During the 2013-2014 school year, Grady’s total unexcused tardies totaled 12,515, the lowest total in eight school years. However, in the 2017-2018 school year, Dr. Bockman improved methods for monitoring student attendance. The school cracked down on attendance, establishing guidelines for late students.

“Last year’s data was the most accurate that we have done as it relates to tardies,” Byron Barnes, the school’s business manager, said. “In the past, when buses were late, we gave them passes but didn’t record the data. We started that when [former Principal Timothy] Guiney left, but last year, we had a full year of capturing those tardies.”

Students often write other students’ names when signing in to the tardy sheet in the morning, so Assistant Principal Raymond Dawson created a plan to use student ID’s to check into school when late. The process to enforce this procedure is lengthy and will not be used until next year.

While Grady is pulling APS closer to the national average, the APS rate for chronically absent students could be worse than reported.

“For APS, our attendance has traditionally been high, with Grady and North Atlanta high schools coming in at the top of the list attendance-wise,” Barnes said.

Grady’s administration focuses on first-period tardy and attendance metrics rather than students skipping class because skipping happens at a lower rate.

“The number of students we know that are class cutters is very small compared to how many are actually late every day,” Barnes said.

Barnes prepares data on attendance, tardies, discipline and academics. He tracks student attendance monthly and prepares weekly reports of unexcused absences in first period.

“The biggest challenge that we have is the number of students coming to school late everyday,” Barnes said. “I identify those students who have been tardy three or more days within a given week, and then I pass that information to an administrator so that discipline can be issued.”

Dr. Bockman attributed the high tardy rate to students getting up late, stopping on the way, parents dropping students off late and students coming from out of district. The staff further instituted new changes this year as well while also trying to jump on consequences quicker.

“The first 20 minutes are the heaviest,” Dr. Bockman said. “If a child needs to eat breakfast, then it adds more time. This year we have tried to do some different things. We have a couple of parents that are volunteering to move lines quicker so that students are not going to Ms. Hall. I tried to eliminate a step so that students are getting into class quicker.”

Grady has over 100 cameras on campus, but about 10 percent aren’t working at any given time, according to Dr. Bockman. New cameras were recently installed in the gravel lot and above the “senior table” in the courtyard primarily for safety and security rather than for student skipping. More cameras will be placed in the E-Wing and the Music Hall in about two months, according to Dr. Bockman.

“The gravel lot needed cameras because it is not safe being close to Piedmont,” Dr. Bockman said. “The cameras are reactive, after the fact. We are not monitoring them.”

Dr. Bockman is very involved in the process of reviewing attendance because attendance affects teaching and learning, she said. Studying report cards every four and a half weeks, she tries to look for patterns between attendance, grades and participation at school.

“For absences, it’s the kids that are not involved in school,” Dr. Bockman said. “A lot of times, it’s the after-school activities that keep you involved. Being involved in activities makes you want to come to school, so I look at kids that might be distanced or detached because those are graduation risks.”

Wednesday skipping has been a focus since Dr. Bockman’s arrival in September 2016, with tighter pressure from teachers and truancy sweeps, which occur a couple times a month using police vans.

“A lot [of truancy sweeps] are in Piedmont Park and Boulevard areas,” Dr. Bockman said. “Wednesdays are big days for that because of advisory. Skipping fourth period is also a big thing here.”

While tardies don’t affect Grady funding, attendance affects its College and Career Readiness Performance Index (CCRPI) score, a calculation that influences the perception of whether or not a school is high-achieving or high-functioning. CCRPI includes Milestones End-of-Course Test results, attendance and a student health survey.

“It is part of the star ratings, budget, and how well we utilize funding, giving the general public a picture of what’s going on academically, and even operationally within the school,” Barnes said. “One reason the Grady cluster is a popular cluster for housing — expensive housing — is because we have great schools … For the informed parent, that is step one when you are looking for a place to live and you are concerned about your children’s education.”

Average daily attendance does affect Grady.

“The school district gets paid for people being in school,” Dr. Bockman said. “The school system gets paid for ADA, average daily attendance.”

Absenteeism remains a large issue for Grady students, and it affects grades.

“Chronic absence — missing 10 percent or more of school days due to absence for any reason (excused, unexcused absences and suspensions) — can translate into third-graders unable to master reading, sixth-graders failing subjects and ninth-graders dropping out of high school,” according to Attendance Works.

Stressing the loss of instructional time, Attendance Works explains that many schools only focus on students with unexcused absences rather than both unexcused and excused absences. Grady is one of those schools, sending robocalls only for unexcused tardies and absences. Absenteeism clearly has an effect on students’ grades at Grady. Students failing at least one class at Progress 1 during the first quarter of the first semester made up 68 percent of the school’s 1,141 absences in August.

“We have a select group of students who are consistently late each day, so the problem is ‘What do we do to help motivate them to get to school on time?’” Dawson said. “Reaching out to parents, going to social workers to see if there is another reason with a home visit, maybe there’s a family matter, economic challenges or disability. The problem is digging down deep enough to figure out what the problem is, and then once we find out, concessions are made for those students because it is not their fault.”