Former president Jimmy Carter passes, leaves mark on education policy, Atlanta Public Schools

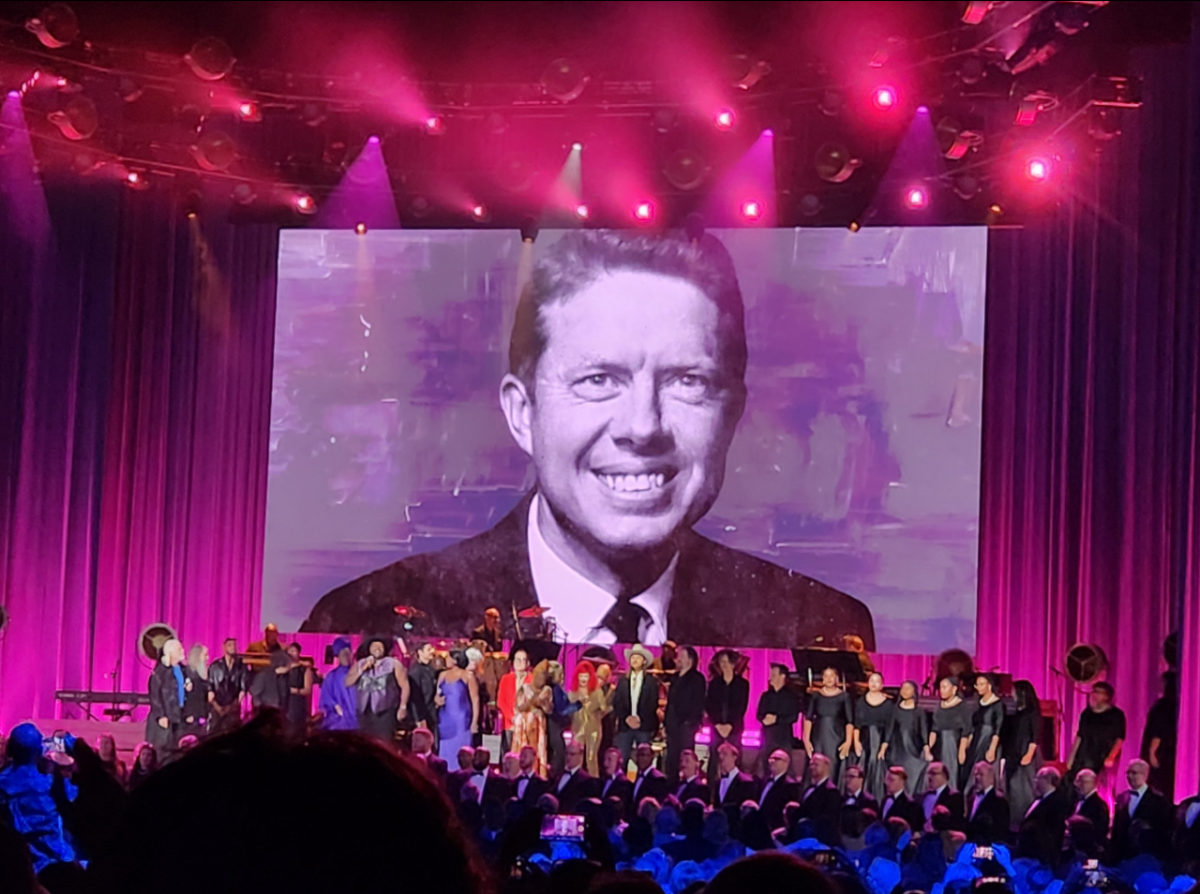

Jimmy Carter, the longest-living former president, died Dec. 29 in Plains, Ga., at age 100. Carter worked to progress education throughout his life, indelibly leaving a mark on the nation and Atlanta Public Schools.

“I have always been inspired by Jimmy Carter and his willingness to serve, regardless if he held a political office or public office or not,” school board chair Erika Mitchell said. “After he passed, I had to ask myself, ‘How do I share the impact that Jimmy Carter had on Atlanta Public Schools?’ He had a huge footprint nationwide, but he had an even bigger footprint in his home state of Georgia.”

Carter’s first public office was as chair of the Sumter County school board in Plains, Georgia, a year after the Brown vs. Board of Education decision, which desegregated schools nationwide.

“His personal history working on a school board meant he understood what it was like to manage a school system,” APS archivist Erika Collier said. “His focus on education existed whether he served on a small school board, as president of a board of education for a major school district, or as [U.S.] president, creating the Department of Education. So, I think his upbringing impacted the choices he decided to make throughout his career.”

Carter collaborated to launch several projects in his time as governor and president that greatly affected APS.

As president, Carter established the U.S. Department of Education to regulate educational standards around the country.

“There are still districts that did not want to desegregate in the 70s and 80s,” Mitchell said. “Having that umbrella from the federal government sending mandates down to what school districts should do is huge. So, I look at how that impacted Atlanta Public Schools, but I also see how it impacts school districts across the nation.”

Carter’s grandson, Jason Carter, who represented Georgia’s 42nd district in the state senate 2010-2015 and ran for governor in 2014, said the Department of Education has made immense improvements to low-income communities and schools.

“The biggest part of his legacy is that he created the Department of Education,” Jason Carter said. “That department has had a major impact all over the country, including just driving a vast amount of funding to the poorest schools in the country, in part because those schools are otherwise funded by property taxes, and you end up with massive inequality around the country.”

Carter’s founding of the Department of Education was the first push to centralize education policy nationwide.

“Jimmy Carter wanted some sort of federal level of keeping an eye on education,” Collier said. “There had not been a single education department on the federal level before; states were responsible for handling their own educational affairs. I definitely think that his push to do this stemmed from his early political career and something that he was very passionate about.”

The Department of Education regulates federal financial aid, education reform and equal access to education.

“Today, free and reduced lunch, one of the components that came from the U.S. Department of Education, makes sure that every child has a nutritious meal,” Mitchell said. “I have had the opportunity to work with the U.S. secretaries of education on several initiatives that helped us down here in Atlanta.”

In 1972, as governor of Georgia, Carter signed the Georgia Open Records Act into law. This established a precedent for transparency and accountability for public institutions, creating a historical record of all decisions within APS.

“[Carter] is responsible for the public having open meetings and open records,” Collier said. “It created the understanding that the public has access and the right to know what’s going on in these very important meetings with these very large budgets, such as education. That is also why APS has such a robust archive because we have access to records in the present and in the past. That’s one of his biggest lasting legacies across the board we see today.”

Jason Carter said the Georgia Open Records Act left a lasting impact on ethics and government transparency.

“He started the Georgia Open Records Act in Georgia, and he continued when he became president with a huge transformation of our ethics law and our transparency laws,” Jason Carter said. “Having a good government that is accountable to the people is important. It’s important from an education standpoint, because it ensures that we’re getting to meet those ideals [of transparency].”

Social studies teacher James Sullivan said having records of government decisions will make the government more honest.

“Having records of government involvement or government meetings [being] open to the public is always going to make the actions of public officials more honest with the public,” Sullivan said.

The Atlanta Project, led by Carter in 1992 after his presidency, targeted challenges faced by disadvantaged families in Atlanta, dividing the metro area into cluster communities supported by local institutions. It created a strong partnership, especially between Emory University and the Booker T. Washington High School Cluster in APS.

“The Atlanta Project was really to help financial inequalities in communities in the Washington Cluster,” Mitchell said. “By addressing inequities, you are improving education. It launched in 1992, with the Olympics following in 1996, creating a real trend in that area. By focusing on that, Carter shows how he really never stopped serving people.”

Jason Carter said the connections created through The Atlanta Project have left an indelible impact on the communities involved.

“The Atlanta Project tried to link up and build connections between the wealthy parts in Atlanta, the corporate infrastructure of Atlanta, the business community of Atlanta and some of the poorest communities in Atlanta, as well.” Jason Carter said. “Of those bridges, some of them still exist today. The Eastlake Foundation, for example, grew out of that Atlanta Project. A huge number of other real connections came out. That quest to bind up the community and across various regional divides, across economic divides, is a big part of who he was and what he was trying to do.”

Sullivan, who was a former lawyer at Kilpatrick Townsend, was reminded of his passion for teaching through The Atlanta Project. His law firm had a partnership through with Washington High School.

“I volunteer[ed] as a mentor at Washington High School,” Sullivan said. “I really enjoyed reaching out to young people and teaching young people, and that led me again on a path that I had forgotten about for a long time to be a teacher. So, I think that was, again, one of the many ways that, like Jimmy Carter and his legacy, even after his presidency, touched the city of Atlanta and touched APS.”

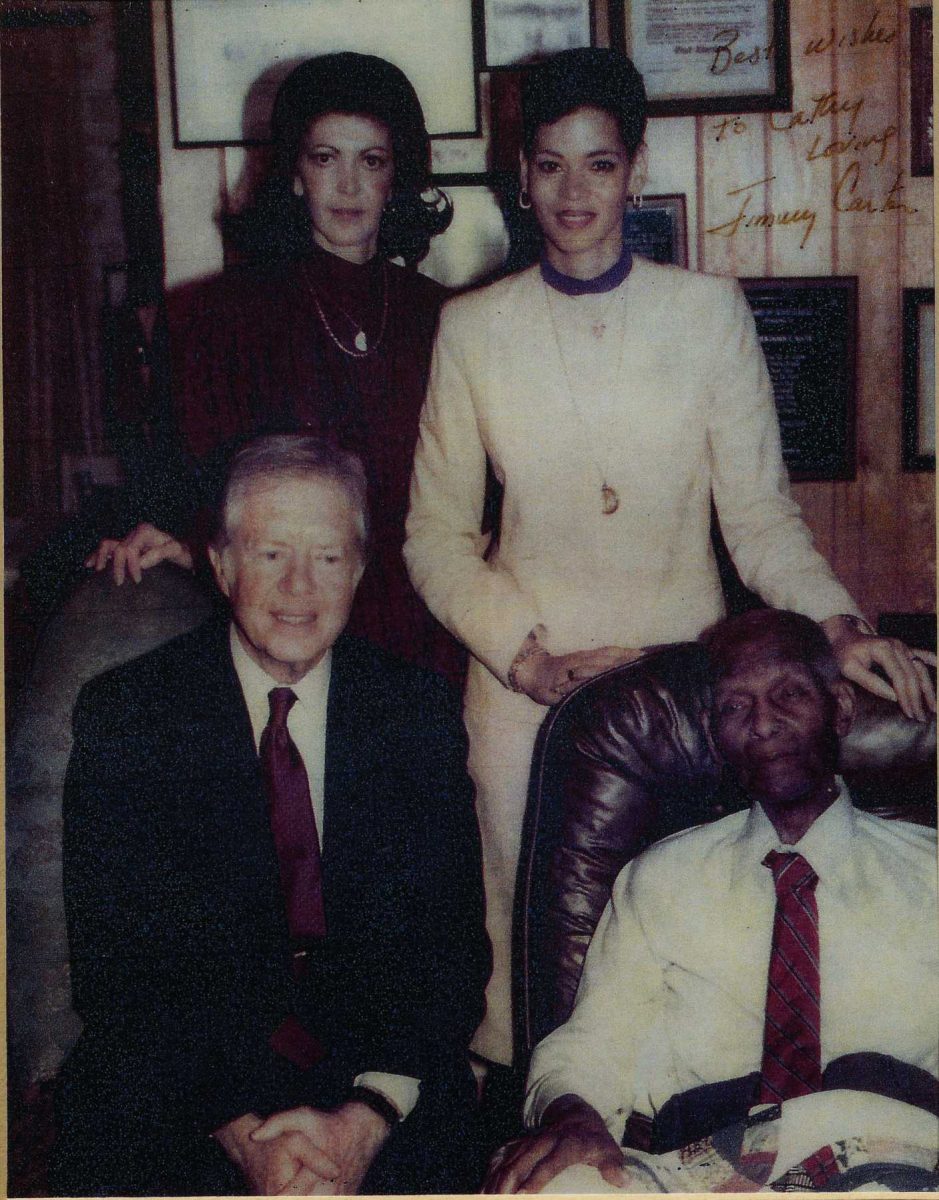

Benjamin E. Mays served as an advisor to presidents Johnson and Carter and served as the first Black president of the Atlanta Board of Education for nine years after working as president of Morehouse College in his career.

“Benjamin E. Mays advised [President Carter] on civil rights issues that African Americans face in this country, which included things that were happening in our schools,” Mitchell said. “So, when you have a president that your school board chair has the ear to, that’s impactful in so many different ways, and I believe we owe a lot of progress for public schools to that relationship.”

Mays High School chorus teacher Garnetta Penn, who is also a graduate of the school, believes their partnership was successful because it was rooted in similar ideals.

“Dr. Mays was from South Carolina, and his parents were sharecroppers,” Penn said. “Jimmy Carter was from Plains, Georgia and he was a peanut farmer. I believe that both of them understood that hard work was very key to their success. They weren’t afraid of hard work, and they also believed that it was important that you don’t sit where you are born, but you have to make some moves to make sure that you can grow in a productive manner.”

Collier said their partnership is reflective of Carter’s ideals and goals for education policy.

“For Carter to be open and to seek out the counsel of somebody with Benjamin Mays’s expertise on education, that is a big deal,” Collier said. “It was very progressive at the time as Mays served as the first Black president of the APS school board and president of a historically Black college.”

This collaboration contributed to the founding of Benjamin E. Mays High School, which replaced the former Southwest High School in the fall of 1981, set to expand education opportunities for students in Southwest Atlanta.

“Jimmy Carter and Dr. Mays relied on each other for the knowledge base that they had,” Penn said. “He looked to Dr. Mays for his depth of knowledge in education and social justice and how that could help the community grow and build in a brighter way.”

Upon its founding, Mays High School was recognized as a science and mathematics academy to promote social mobility for its students.

“Jimmy Carter and Dr. Mays both wanted students to have a chance,” Penn said. “Dr. Mays believed that students, if given the opportunity, could absolutely flourish in the areas of math and science, and for many years, that was very much the case. The mission of Mays [High School] has always been the same, which is that every child has to be given the capacity to grow and to strengthen with educational opportunity.”

With an emphasis on education, Jimmy Carter left a clear legacy on educational policy and approaches.

“The idea that all children can learn, given the opportunity, has always stuck with me,” Penn said. “He wanted education, not just for the elite, but for everyone across the board, and so, as a citizen in the state of Georgia, all of my life, I grew up watching Jimmy Carter advocate for social justice and education and opportunity.”

Jason Carter said his grandfather’s leading value on educational policy was equal opportunity.

“One of the first things that he did was announce at his inaugural address [as Georgia governor] that the time for racial discrimination was over,” Jason Carter said. “Then, he proceeded to make a huge number of changes in efforts to ensure that the schools that had been separate and unequal would begin the long process of trying to make sure that we educate every kid to give them equality of opportunity. Obviously, we’re still far from that, but that’s the goal.”

Fairlie Mercer is a senior and this is her third year writing for The Southerner. She currently serves as an Editor-in-Chief and is excited for her second year as an editor. Outside of journalism, she enjoys hanging out with friends and dance.