While juggling a part-time job at a local bike shop with pursuing a graduate degree in English literature, Margaret Edson spent the bulk of her leisure hours working on “Wit,” a personal play she would have never foreseen to earn the Pulitzer Prize. Thirty years later, her stage is a vibrant AP World History classroom where her students are captivated by her unique and innovative storytelling.

In “Wit,” Professor Baring, an expert in 17th-century English literature, grapples with her limitations after being diagnosed with ovarian cancer. The play navigates her journey through treatment and self-discovery, revealing that expertise in academia does not ensure proficiency in life’s basic human experiences.

“To me, it’s about a person unlearning and learning,” Edson said. “This character is a lot like me, except that I have let go of a wish to be correct, and she [Baring] hasn’t yet. The setting of the play takes place in the hospital, which I know about, and in the world of the academy, the study of literature, which I know about, but the movement of the play, is not cancer or literature, it’s about growing into your true self.”

Born and raised in Washington D.C., the roots of Edson’s playwriting were embedded within her childhood community.

“We used to put on plays in our neighborhood,” Edson said. “We had a very verbal group of kids in our neighborhood. We put on plays, and one of the neighborhood kids living right next door was Julia Louis-Dreyfus, she was on Seinfeld.”

Being surrounded by a supportive community was integral in shaping Edson’s aspirations.

“Growing up in D.C., there’s always a lot happening in live theater,” Edson said. “My family had an interest in that, and my school had a very strong music and theater program. I loved participating in that.”

However, while driven by the pursuit to write “Wit,” Edson knew she did not want to consider a career as a playwright.

“My goal was never to be a playwright, I just wanted to write this one play,” Edson said. “I had this set amount of time, and this idea that I’ve been thinking about for several years. I just decided on my own to write it, [which] was extremely difficult [and] very challenging. Every word was just agony. It was very, very hard to do, but it was something I really wanted to do.”

Although feeling accomplished after completing the play, Edson was met with a wave of rejections when sending it to theaters across the country.

“I felt like I had done what I set out to do,” Edson said. “There was not any path that I was on that was going to get the play ever produced. I felt like I wrote the play I wanted to write. I sent it out to every theater, every nonprofit theater in the country; I sent out 60 letters to theaters, and the play was rejected by everyone. And I thought, ‘Well, that’s the end of that story.’”

Against all expectations, the Californian theater company South Coast Repertory decided to run “Wit” in 1995, over four years after Edson produced the play. However, the play had to undergo abundant changes before being performed, cutting over an hour out of the original play.

“South Coast Repertory in Costa Mesa, California did a staged reading of the play and then decided based on that, to do a full production,” Edson said. “It was a very successful production, and it was held over three times, so they extended the run. But after that, no other theater would pick it up. Even though this very prestigious regional theater had a very successful production, nobody else wanted it.”

After two years of no interest in the play, the Long Wharf Theater in New Haven decided to stage the play.

“After two years of nothing, a theater in New Haven, Connecticut, picked it up and did an excellent production,” Edson said. “That production was reviewed by the New York Times, which is very unusual for the Times to leave Manhattan to review a play. That review encouraged that theater to think ‘Well, we should move this production to New York.’ And so a year later, it moved to New York.”

From there, “Wit” finally gained popularity, seeing productions across the country.

“It moved to a bigger theater, and that’s where it achieved being noticed,” Edson said. “Then it stayed in that theater for a while, and was made into a film by HBO that was directed by Mike Nichols and starred Emma Thompson. That film won the Emmy Award in 2001, for the best film. Now, the play has been translated into dozens of languages.”

As “Wit” gained momentum, Edson found herself simultaneously embarking on another path: education.

“By then, I had gone to grad school and then decided to stop with a master’s and not get a PhD because I was a volunteer tutor in an elementary school, and every week, I’d like my tutoring more and more, and my graduate work less and less,” Edson said. “I decided that after my graduate work was over to go into public elementary school teaching. So, while all these things were happening with the play, I was beginning my teaching career.”

Guided by a passion for teaching, Edson veered away from professional playwriting.

“The possibility of becoming a professional playwright was not my path; that was not what I wanted to do,” Edson said. “Once I started teaching, there was no turning back and it was clear that was what I wanted to do.”

In 1998 after her teaching career began, Edson was informed she had won the Pulitzer Prize for “Wit.”

“I was teaching kindergarten and was called into the principal’s office, [where] it was announced,” Edson said. “And then the next day, the press office in New York sent doughnuts to my class. All my students had little powdered mustaches from eating powdered donuts in my class. It was news because if a writer wins the Pulitzer Prize, that’s interesting. But if a kindergarten teacher wins the Pulitzer Prize for writing a play about 17th-century poetry, that’s more atypical.”

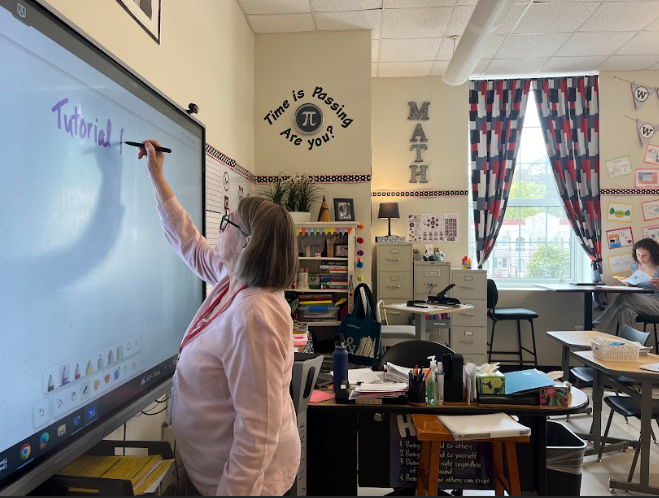

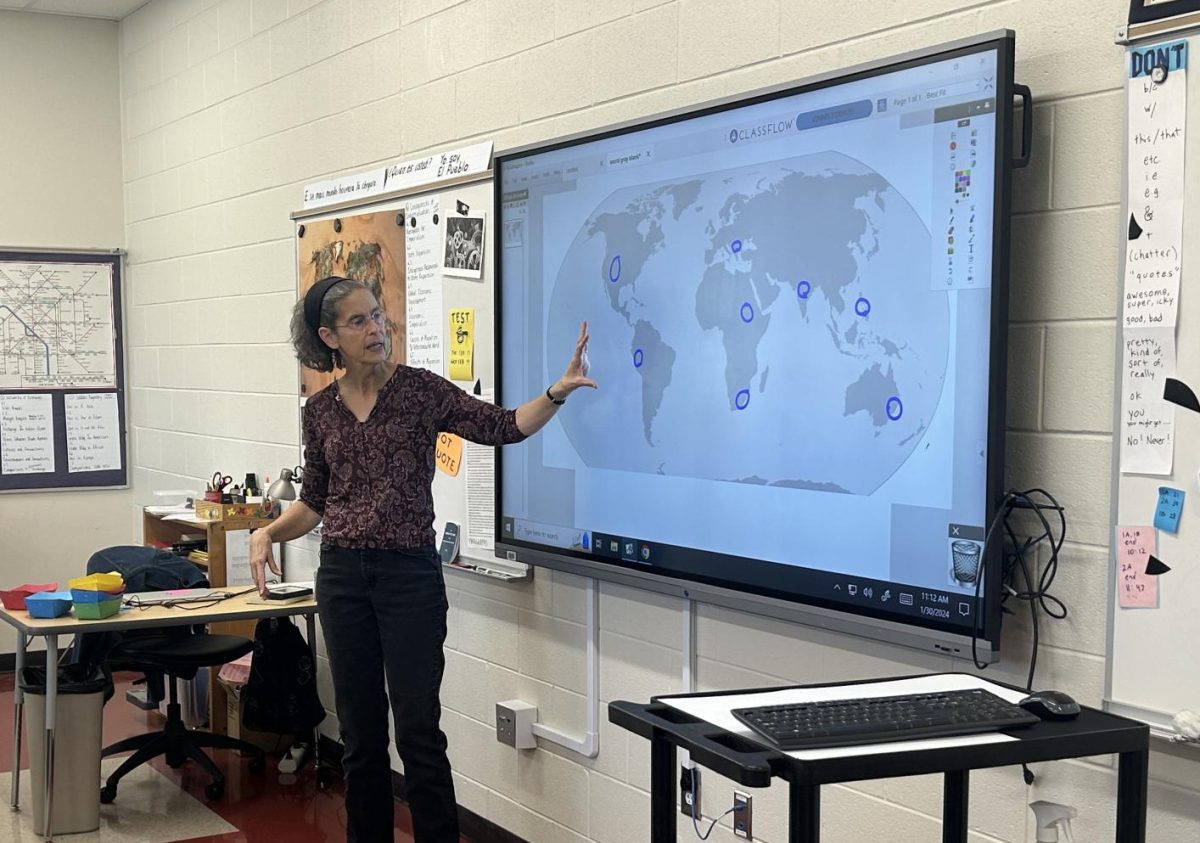

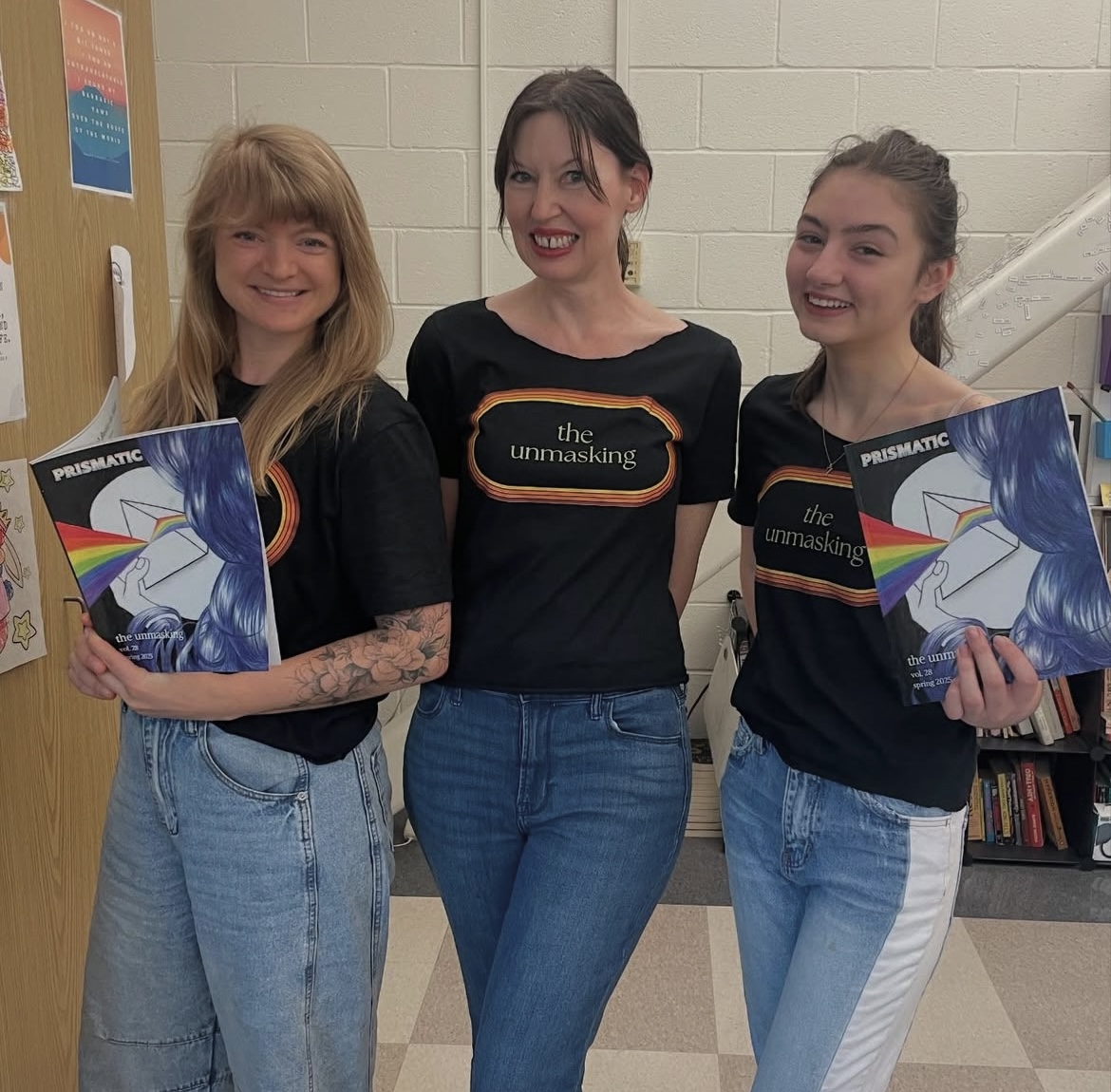

Despite the acclaim “Wit” garnered, Edson’s focus shifted definitively toward education. Edson has taught for 31 years, 25 of which were in Atlanta, and has taught elementary and middle school curricula, with this year being her first to embark on the challenge of teaching at the high school level. Although the transition to teaching high school has been demanding, Edson said she is committed to facilitating her students’ learning.

“I hope that my students see the sincerity of my effort, and my commitment to their learning,” Edson said. “I just love learning new things, and I love sharing them with my students. I love thinking of ways to present them and creating lessons.”

AP World History teacher Kelly Wren sees Edson’s playwriting skills translated in the way she teaches.

“Ms. Edson is a storyteller,” Wren said. “Being a storyteller is essential when you’re teaching history like this. I can just tell from the way that we collaborate that she’s probably really engaging for her students telling stories about what they’re learning.”

Howard Middle School teacher Abbie Hurt had previously worked alongside Edson before Edson transitioned to Midtown. Hurt said she has noticed Edson’s unique ability to connect with students in an educational atmosphere.

“Everybody knows that she’s a fabulous educator,” Hurt said. “I’d see students just sitting in her class completely captivated, mesmerized by her delivery.”

Although Edson is still acclimating to the Midtown environment, Wren said Edson has contributed meaningfully to discussions surrounding the AP World History curriculum.

“She’s a character,” Wren said. “She brings energy and experience and loves what she does. She’s passionate about what she does, and it’s so evident when you engage with her. She has this ability to think about content in different ways and to ask really fantastic questions that lead us into great discussions about the content.”

Sophomore Ocean Feng said she appreciates Edson’s efforts to captivate her students.

“She really goes into detail with everything she teaches and is super passionate about it,” Feng said. “She also gives us a lot of feedback on our work, and you can tell she spent a lot of time on it.”

Hurt recalls Edson’s ability to enlighten both students and other educators throughout the day.

“I think the most poignant memory that I have of her is the love that she poured into students,” Hurt said. “I remember days when she seemed to just be intuitive enough to know who needed some extra attention that day … she’d celebrate them in the most animated way that only Maggie Edson could do, and they just walk away beaming. I’m sure that some of them still value those remarkable short moments when they were the most important person in the hallway on that particular day.”

Edson’s fundamental goal is that her students leave her class having helped shape the world.

“I want [students] to see the world as an opportunity to participate, not as something other people are doing, but something that we are actively creating,” Edson said.

![STANDING STRONG: Hills4ATL founder A.B Bailey [left] leads workouts ranging in intensity every week, including hill climbs and yoga. Bailey believes that his workout classes bring together Atlantans of all ages for unique workout opportunities, as outlined from the beginning of Hills4ATL.](https://thesoutherneronline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/hills-1200x800.jpg)