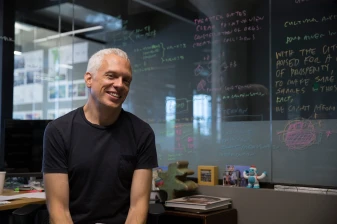

Gravel designed BeltLine, changed neighborhoods

Ryan Gravel was instrumental in the planning and development of the BeltLine, a popular hangout-spot for adults and teens in Atlanta.

January 14, 2023

Many Atlantans and outsiders around the nation know of the BeltLine. What people may not know is the man behind the project.

The idea for the BeltLine all began in high school when Ryan Gravel found himself drawing house plans in science class at Chamblee High School. Inspired by a friend’s aspiration to study architecture in college, Gravel did the same.

“It was very coincidental,” Gravel said. “I thought, ‘that sounds like a good idea,’ and it just took off from there. It’s something I’m pretty good at, and it’s just a way of thinking and imagining the world in this unique way.”

Gravel, a father, husband, author and urban designer, was a graduate at Georgia Tech when he conceived the idea to create the BeltLine. During his final year at Georgia Tech, after studying there for both his undergraduate and graduate degrees in architecture and city planning, the idea for the BeltLine was formed as his master’s thesis required for graduation.

“I’d studied the city a lot;so I knew that there were abandoned railroads circling the city, and that’s when I thought of the BeltLine idea,” Gravel said. “But it was just an idea. I’d never imagined we would actually build it; I just wanted to graduate.”

Before coming up with the idea, Gravel had embarked on a study abroad program in Paris where he fell in love with the city’s walkability.

“I began to recognize the role of the city and how it was shaping my life,” Gravel said. “[Being in Paris] created opportunities that I hadn’t had, or been available, in Atlanta. I became really fascinated with the city.”

His fascination didn’t stop there. When he returned to the states, back to his home where he grew up in Chamblee, he instantly longed to be back in Paris. Driving to and from work along Interstate 285, Gravel realized that wasn’t what he wanted to do.

“It was miserable. I didn’t like the kind of lifestyle that the highway was offering,” Gravel said. “I saw the highway as a barrier between the life I wanted. So, I started imagining what it would take to make Atlanta the kind of place that I would want to live.”

After graduation, Gravel worked as an intern-level architect. This position was short-lived as the BeltLine came to life a few years later when some colleagues encouraged him to show the idea to other people.

Gravel quit his job and created a nonprofit, alongside some work associates, called Friends of the BeltLine, where he worked a few years. When the Great Recession hit in 2007, he began working for himself. After bouncing from various companies, Gravel started an urban design consulting company called Sixpitch in 2015.

His wife Karen Gravel, also an architect, witnessed the making of his idea prior to their marriage.

“I remember the very first public meeting was held at the Virginia-Highland Church in the basement; I remember it like it was yesterday,” Karen Gravel said. “It’s funny to think back on that to now and think about how much [the BeltLine] has grown.”

Building the BeltLine was no easy task. Once the plan got started, the community got excited about what the BeltLine would offer. Gravel and his associates went to neighborhood meetings to talk about the project.

“There’s a lot of sides to [the project], but the reason we’re building all of it today is because the people in the city fell in love with this idea for the future,” Gravel said. “[Community members] saw themselves as part of it, and then actually got engaged.”

At the time, it seemed like an immense project that would be hard to implement.

“It was this huge idea for land that we didn’t own, to be paid for with money we didn’t have, in a state that was really hostile to everything we’re doing,” Gravel said. “So people were nervous about it, but also excited about what it would mean for the city’s future.”

Gravel said the reason for some hesitation toward the project was fear of gentrification in the surrounding areas and how the BeltLine led to increased taxes and rents.

‘“How are we going to make sure everyone’s included?’ was something that we wanted to make sure we thought about,” Gravel said. “That doesn’t mean that we don’t do the project or that the ideas aren’t beautiful, it just means that we have to do it in ways that ensure that people get to stay and enjoy the benefits.”

Because of those concerns, 15% of funds from the BeltLine go to affordable housing.

Business partner Hannah Palmer has worked on and off with Gravel since 2012 when the Eastside Trail was just being completed. Palmer said finishing the project felt like the beginning of a major transformation, and she was excited to work with Gravel.

“[Gravel] knows so much about Atlanta’s history, and about the different plans and developments that are gonna be making up Atlanta’s future,” Palmer said. “So, he has a unique perspective, and because he’s been working at the grassroots level for so long, it feels like Ryan knows everybody in Atlanta, and he’s just deeply embedded in a lot of different projects that are making Atlanta an exciting place to live right now.”

Jonas Gravel, Ryan’s son, has always felt his dad has been an advocate for green transport who strongly believes in walkability in cities.

“He walks or bikes everywhere,” Jonas Gravel said. “Atlanta isn’t very walkable, and a lot of people don’t think that Atlanta is walkable, but [he] always uses the BeltLine to travel in his day-to-day life.”

Lucia Gravel, Ryan’s daughter, sees her dad’s approach to having big aspirations in herself.

“He believed that his idea would transform Atlanta into a better city,” Lucia Gravel said. “Before the expansion of the BeltLine, he took [the family] biking, and I remember seeing it when it was overgrown, and there were train tracks that had been taken apart and obviously hadn’t been used, and now looking back, it’s come a long way with all of this development that has formed.”

Palmer saw Gravel’s book, “Where we Want to Live,” as a kind of personal manifesto and narrative that won peoples’ hearts into a better vision of the city.

“He wrote not so much as an architect or a scientist or a technocrat would write it,” Palmer said. “I think it’s the best way to tell a story, and he really succeeded in telling his story.”

Ryan Gravel saw the making of the BeltLine as an incredible story that he wanted written down.

“The real story of it is really important, and the similarities to other places that connect everyone together is also really important,” Gravel said. “It became a bigger story of the role of infrastructure in our lives. If you can tell a story that can move people or compel them to make better decisions then that will really transform an environment.”

Gravel saw a bunch of rusted train tracks as an opportunity that he didn’t want to pass up.

“I believe in the ability of the city to shape, to make our lives better and the design matters the way that the city is built.” Gravel said. “So, I enjoy the work, and I see a need for it. If I can make a living doing it, then that’s what I’m gonna do.”