Out-of-district students risk repercussions for success

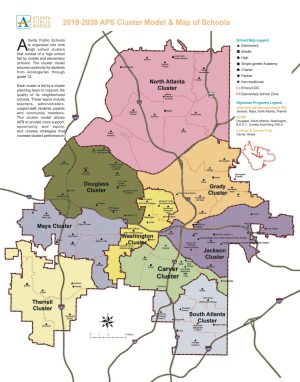

DIVIDED UP: The Atlanta Board of Education divides Atlanta Public Schools into nine different school districts. Students must attend the school in the zone where the residence of their parents/legal guardians is located unless they have administrative approval to enroll elsewhere.

March 8, 2022

Education has power and, with 90 percent of American students attending public schools, school districts and zoning has become crucial to either securing or unraveling a student’s educational future. Out-of-district students have been caught in a Catch-22 of securing a quality education or following district policies.

Currently, Atlanta Public Schools has approximately 300 cases of potential enrollment fraud per year, 25 percent of which are founded, according to the APS Office of Student Assignments and Records.

Midtown’s reputation of academic and extracurricular excellence has driven some students to abandon school district zoning requirements in search of better educational opportunities. From 1947 until last spring, Midtown was known as Grady.

“Midtown High School has a great reputation in terms of their academic rigor, even their arts programs,” Inaya Abdul-Haqq, Grady Class of 2021 alumna, said. “And the district that I lived in — I knew it wasn’t going to be as academically challenging.”

Concerns about routine, academic environment and neighborhoods surrounding the schools are only some of the factors that influence families’ decision to take the risk of having students live out-of-district. Educational environment remains a recurring theme that is crucial to students’ decision to take on the risks.

“My parents just felt like we’d [her siblings] get a better education and would have a more positive experience if we went to a school like Grady, or even a school like North Atlanta.” May Tyler*, a Grady alumnus, said. “These school districts are just designed differently. Across the board, the opportunities were going to be better. Students also have that mindset where they prioritize school and doing well in school is a big part of their lives. That’s what my parents wanted for me, too.”

For students with siblings, the risks and sacrifices of attempting to ensure a better education and opportunities are even greater.

“There was always the concern with my parents of having to leave the house extra early because we don’t know what the traffic’s going to look like in the morning,” Tyler said. “We didn’t want the school getting suspicious and looking into my siblings and seeing where we live. Because my mom worked at a school, she had seen that happen if students have too many absences or too many tardies. Schools will send a social worker to the student’s school to see if there’s any issues with their home life.”

Going Out of the Way

Commuting remains one of the most pressing obstacles for out-of-district students, and often makes them commit more time to school than others.

“I usually got up around 6 a.m and left around 7 a.m to get to school by 7:30 a.m or 7:45 a.m and then waited for classes to start,” Abdul-Haqq said. “So, it was a little bit of a commute. Depending on traffic, it was 30 minutes to an hour, to and from school. It’s definitely a more considerable commute than other students would have.”

The commute to and from school also had an impact on students’ extracurriculars.

“I tried to be involved in as much as I could,” Tyler said. “ When I got to high school, I did Beta Club and mock trial, which took up a lot of time. I also did Latin Club, student government, and I tried to get involved in a little bit of everything. So, even though there were all these challenges and hassles, we always made it work, and my parents knew that it was something that I enjoyed and would benefit me and even look good on my resume. So, we tried to make time for it all.”

Some students had to sacrifice meetings for their extracurriculars because of the issues they faced with getting to and from school.

“I had to work out my schedule with my parents and my siblings to see if they had anything else going on, so that they could take that half an hour drive to Grady so that I could go to those meetings,” Tyler said. “There were a lot of times where I had to text one of the members in Drama Club or my director and be like, sorry, I can’t come to rehearsals today; something came up; I just had no one to drive me home.”

With siblings, the problems and stresses of commuting were exacerbated.

“It was definitely challenging,” Tyler said. “Once we all got a little bit older, I think it became easier for them because we realized that even though they’re making sacrifices on their end, we also had to make sacrifices on our end. My brother was in the marching band; so, sometimes, even if I didn’t have to do something after school, I was in the band room with my brother because I couldn’t have anyone come pick me up, drive me home, and then have them come back and get him.”

Alternatives for Inadequacies

Some options exist for out-of-zone students to attend schools out of their zones. APS permits parents to apply for their child to attend a school they aren’t zoned for, providing it has the capacity, through an annual application window. This window is typically open in March for three weeks.

When schools or grade levels receive more applicants than available spots, students are entered into a lottery system to sort spots. Resident students receive priority in the lottery system. Non-resident students are also required to pay tuition for the schools they are accepted to, Cory Edwards, director of Student Assignment in APS’ Office of Student Assignments and Records confirmed.

While out-of-district students seek better educational opportunities, their enrollment can also result in overcrowding at schools.

“Out-of-zone students create resource and facility planning capacity challenges,” Edwards said. “For example, if a school can safely house 500 students, and 650 students enroll, this could result in overcrowded classrooms and higher teacher-to-student ratios. Families committing residency fraud also unfairly limit the number of available school choice spaces through application processes facilitated by the Office of Student Assignment.”

Beginning Anew, Feelings of Isolation

Some former students like Noelle Allen, a then Midtown student who transferred to North Atlanta, were unable to complete their full four years at Midtown. During her sophomore year, Allen was ruled out of district, in this instance due to an administrative error.

“When I got to high school, it was a thing where we made sure that they had the new address, but what happened was somebody forgot to record it,” Allen said. “So, instead of in ninth grade, and them being like, ‘Oh, you don’t live in this place anymore. You can’t go here,’ they figured it out in sophomore year, when they kept sending mail to the address that I moved from, and it wasn’t being received.”

Allen attempted to find ways to stay at Midtown, but her efforts were in vain.

“So, I got the note the first semester of sophomore year, and we requested hardship transfer,” Allen said. “I thought I would be able to continue going throughout high school, but they said I had to transfer schools. It was really interesting because I was halfway through high school. I had already established relationships with all these people because I went to middle school with them. And then out of nowhere, I just had to move and pack up my life and then move to a different school and start completely over.”

Allen requested a hardship transfer to North Atlanta that was granted. Allen was originally zoned for Therrell. There, she participated in a variety of extracurriculars and enrolled in North Atlanta’s IB program. Despite her newfound access to resources that would have been denied to her at her zoned school, the experience was still emotionally taxing and isolating.

“I was really angry, and I was really sad about it because I have known these people since seventh grade,” Allen said. “And then I had to start over making friends in a school where everybody had already established their relationships since it was junior year, and I felt like I was pushed out. In a sense, it felt like I was being excluded. And it made me feel like there was no room for me in this community that I had been in for so long.”

Acknowledging the Whole Student

APS attempts to account for students’ social achievements and current lives before they are removed from the school they are not zoned for.

“Equity is a major focus area for APS,” Edwards said. “APS must respond fairly to all cases of out-of-zone students. Students are our first priority. APS attempts to allow most identified ineligibly enrolled students an option to complete the remainder of the semester at the current school.”

Students have noticed that those who live out of district like them often come from the same racial backgrounds.

“What I’ve noticed about the out-of-district students is that they look like me — they are Black, and the schools in their area aren’t up to their standards,” Allen said. “They want to go somewhere else and contribute to the community there because they’re more likely to get something in return.”

Midtown’s Legacy of Excellence

Out-of-zone students believed that without Midtown, they wouldn’t be where they are now.

“I don’t know what my high school experience would have been, not being in Midtown High School,” Abdul-Haqq said. “I have honestly thought about it as I was applying to college and getting into college. It was a really impactful and special part of my life, and I don’t know what kind of student I would be now if I didn’t have that environment.”

Midtown’s academic, extracurricular and athletic reputation plays a role in students’ experiences.

“I can’t say how different it would have been if I had gone to school in my zone, but I know that the opportunities and the experiences that I had at Grady were phenomenal,” Tyler said. “The Grady name, or Midtown now — it carries weight in the state of Georgia.”

Midtown’s relationship with organizations such as the Posse Foundation, an organization that identifies academically-talented students and offers a full-tuition scholarship to recipients who attend their partner schools, also influences students’ future success. Posse’s partnership universities include schools such as Dartmouth College and Vanderbilt University.

“Without Midtown, I don’t think I would have gotten Posse,” Abdul-Haqq, who was a Boston University Posse scholar, said. “A lot of what looked good on my resume was because of the school that I went to. The counselor that I had was willing to recommend the extracurriculars. I would have most likely gone to Georgia State University. Posse was something really important to me, and Midtown High School allowed that to happen.”

Midtown and schools like it influence students’ futures by granting them opportunities that cannot be found at all public schools.

“Everybody has the right to pursue education,” Allen said. “Let’s not pretend like education is the same everywhere — because it’s not. People recognize that if it was the same everywhere, that it wouldn’t matter what school you went to. People want to go to good schools so they can do things later on in life.”

With Midtown’s push for equity, some in-district students at Midtown believe out-of-district students play a role in this conversation.

“I think the issue is with students who are out of district, it’s not a Black and White issue,” senior Aaliyah Rapping said. “I think that when dealing with out-of-district students, we have to take a holistic approach and look at who they are as a student and why are they out of district — and that’s the problem. It’s preventing kids who really could benefit from receiving educational opportunities from ever getting that chance to.”

*May Tyler is an anonymous name