Midtown’s name change does not fix existing racial stratification

Behind Midtown’s name change lies the same racial segregation that still existed when Midtown was Grady. Instead of turning towards more white liberal displays of ‘good intentions’ such as the name change, I implore that we direct our actions towards making actual changes in the racial stratification at our school.

Following a series of fiery Zoom calls surrounding racism and our school’s former namesake Henry W. Grady last spring, the school district administration greenlit a long-debated name change. Now, as we near the end of our first semester as Midtown High School, this is an important time to reflect on the progress we have made in terms of racial justice and equity.

At the time of the name change, I had my reservations. I was concerned that the renaming would serve merely as a smokescreen for the ongoing forms of anti-black violence, racial segregation and profiling that exist in our school and communities. Most notably, I was concerned that our collective focus on the name of our institution was obfuscating the very logics that would allow people in power to name a school after an avid white supremacist in the first place. Now that we are back in school, it is evident that those concerns were correct.

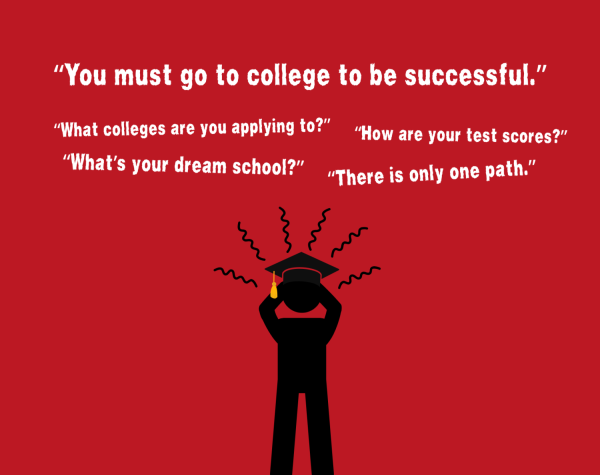

For most white students at the supposedly new and improved Midtown High, a quick glance around whatever classroom one finds themselves in or a quick evaluation of one’s own friend groups would find that there are very few Black or Latino students in those spaces. The vast majority of students that I have spent my duration of high school with are white upper class students. Although some lack of diversity can be attributed to personal bias, the bulk of it must be assigned to the ways that our classrooms are segregated and the ways that that division quels most meaningful interactions between socioeconomic classes and racial groups at our school.

Within the community at-large, historically Black neighborhoods continue to gentrify, thus making our school more racially and economically homogeneous. Driving through Old Fourth Ward, one cannot help but notice signs that celebrate the construction of new housing by proclaiming that it only cost a reasonable ‘$500,000 and up.’ Due to generational redlining and the concentration of wealth in the hands of the few, most working-class people cannot afford to live in a townhouse that costs hundreds of thousands of dollars. This change in housing stock has torn apart predominantly Black communities and has had a direct influence on the steady decline of Black students at Midtown High School over the last decade.

Instead of turning towards more white liberal displays of ‘good intentions’ such as the name change, I implore that we direct our actions towards making actual changes in the racial stratification at our school. The school cluster should end discriminatory ‘Gifted and Talented’ programs and instead invest those funds into the families that most need the extra support. The Midtown administration must stop turning a blind eye to the blatant segregation and, instead, prioritize integration on a classroom basis. By committing to these actions and many more policies that create equity, we as a school community can still earn a new name.

Anna Rachwalski is a senior and this is her third year writing for the Southerner. Outside of the newspaper, she is president of the Quiz Bowl team, is...