Recommended new school name spurs backlash

Despite Midtown garnering twice the amount of support as Ida B. Wells, according to a community survey, the Grady Renaming Committee voted to recommend the name of Ida B. Wells to the Board for a final vote. This decision has spurred backlash from some who feel that the committee’s decision does not reflect the community.

October 27, 2020

A renaming committee’s recommendation of Ida B. Wells as Grady’s new name rather than majority-supported Midtown has spurred community backlash.

“I was saddened by the meeting last week,” said parent and school governance team member Sharon Bray, who supported the Midtown name and thought the majority input was overlooked. “I was not happy that people weren’t representing their constituencies. I felt like when you’re appointed as a representative to a committee, your primary job is to represent the group that you were appointed to represent.”

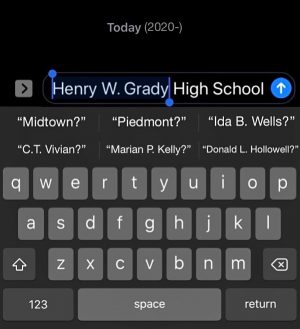

Throughout the school’s renaming process, which began in the summer, there have been multiple community input opportunities, including surveys and discussion at committee meetings. The committee narrowed a list of more than 50 suggested names to five: Freedom, Thomas E. Adger, Ida B. Wells, Piedmont and Midtown. The committee created a survey to gather input on the short list, asking each participant to self-identify as a student, faculty member or community member and to submit their preferred choice and explain their rationale. The survey did not have a category for alumni.

Grady is the oldest school in Atlanta Public Schools, with a history dating back to 1872, the year the Atlanta City Council created the district. Founded as Boys’ High, the school officially became Grady in 1947 when it converted to a coed institution. Henry Grady’s name first appeared when the main building on Charles Allen Drive was being constructed in 1922 and the campus housed both Boys’ High and Tech High, according the book “Boys’ High Forever: The History of an Extraordinary Atlanta Public High School,” which chronicles the school’s early history through 1947.

“It’s a pretty major thing,” said Grady parent Richard Weinstein. “That school has been around [and] that name has been around for decades … I think it’s important that the name change reflects the will and the desire of the constituents in the community.”

Any decision involving the renaming of the school should have input from past and present members of the school community, said Howard Graves, a former researcher who served on the Confederate Symbols Committee at the Southern Poverty Law Center. Graves participated in a panel discussion with alumni after the name change was announced.

“This is a community discussion,” Graves said. “The alumni of Grady High School and the current students, all of those voices need to be heard.”

Conflicting Results

Ida B. Wells was recommended after the committee members submitted their votes at an Oct. 20 meeting. District 1 Board Representative Leslie Grant, District 2 City Councilman Amir Farokhi, 1996 Grady alumnus Celeste Beal and 2020 Grady graduate Jay Hammond voted for Ida B. Wells. Grady Assistant Principal Carrie MacBrien and Council of Intown Neighborhoods and Schools (CINS) Representative Janet Kinard voted for Midtown. NPU-E Representative Courtney Smith voted for Piedmont.

According to the survey, about 62 percent of 1,619 respondents supported a place-based name. Specifically, 42.7 percent selected Midtown, while 21.5 percent supported Ida B. Wells. In each of the stakeholder groups, the majority of support was for Midtown. During the meeting, MacBrien said based on the feedback she studied, Midtown was the top choice among students, staff and the community.

Given this data, the committee’s Oct. 20 decision left many community members frustrated and under-represented by the renaming process.

“If they were sincerely seeking community input, that vote split … certainly doesn’t sound like the community’s decision was one they necessarily valued as much as they might have,” Graves said.

According to Timothy Crimmins, Professor of History and Director of the Center for Neighborhood and Metropolitan Studies at Georgia State University, originally Atlanta’s schools were named for locations. Elementary schools had names such as English Avenue School and Capital Avenue School and the high schools had generic names like Boys’ High and Girls’ High or Commercial High for the vocational school, Crimmins said.

Just as more than 70 percent of survey respondents wanted Grady to bear a name that doesn’t honor a person, more than 80 percent of the 468 member schools of the Georgia High School Association are not named for people. Most are named for the communities, cities or counties they are located.

Crimmins says that by the 20th century, schools began to be named after prominent figures in Atlanta or Georgia history like Grady or President Franklin D. Roosevelt, which was the new name for Girls’ High in 1947 when it became coed. Many schools currently named for people are in Metro Atlanta or other urban areas of the state such as Columbus, Augusta or Macon.

Grant, the school board member who was re-elected in 2017 with 74.9 percent support and chaired the renaming committee, acknowledged the decision did not represent the majority, but said that the survey was intended to gather community input and the decision was not based on the majority rules. According to Grant, this stance was made clear at the public meetings, and therefore, was not directly addressed on the survey.

“I thought it was very clear throughout the process, for those who are listening, that it wasn’t a numbers game,” Grant said. “Could the survey have been worded differently? Yes. But, the process is that the committee makes the recommendation to the full board.”

Board Chair Jason Esteves, who commissioned the renaming committee, said the survey was just one indicator for the committee and had the decision been based on popular vote from the offset, the survey would have been designed differently. He added had the goal been a numbers game, the committee would have never decided to change the name from Grady because alumni petitions protesting the change had more signatures.

“If we’re just doing it based on numbers, then we shouldn’t have renamed in the first place,” said Esteves. “It’s not based on numbers. It’s based on what we think is right.”

According to Grant, basing decisions purely on the numbers is not desirable because a lot of voices aren’t represented in community polls. She said it is her responsibility to “listen differently.” Grant said she read every submission and that no one’s opinion was ignored. She said the decision was one of quality rather than quantity.

“There was a quantitative and qualitative component to this,” Grant said. “The quantitative piece clearly came in, in favor of Midtown. The qualitative piece was much stronger for me. The rationale for wanting it named after Ida B. Wells was just richer, more passionate and more meaningful, I think, than the reasons they wanted it named Midtown.”

Sometimes, leaders addressing the legacies of white supremacy make decisions that appear to be in self interest, Graves said.

“Globally, looking at ways in which institutions have dealt with the legacy of white supremacy, structures or monuments in their areas, a lot of times, people in positions of power are more likely to make a decision they think will reflect well on them personally than necessarily making the tough call. I have seen that happen,” Graves said.

Community Reaction

Literature teacher Susan Barber voted for Midtown but recognizes the “poetic justice” and rationale behind naming the school after Ida B. Wells. However, given the quality over quantity argument that some committee members made, Barber is confused about why the committee put out the final survey.

“I think it’s fine if the naming committee and the board want to name the school whatever they want to name it, but why ask for input, especially if you’re going to have overwhelming input, and then it was easily dismissed, especially for how large of a percentage it was,” Barber said.

Among the students who filled out the survey, Midtown received 153 votes, Piedmont received 68 votes and Ida B. Wells received 50 votes.

The renaming committee initially extended the renaming process to maximize student input.

Toward the beginning of the meeting on Oct. 20, Hammond, the 2020 graduate and the committee member representing the current students, acknowledged that, even in his own research, he found the majority of students preferred Midtown. Despite this, Hammond advocated for Ida B. Wells.

Although committee members making their case can be part of the process, some felt Hammond’s arguments were not consistent with the views of the constituency he was appointed to represent.

“While I think Jay Hammond is an amazing person and had really passionate, well-researched arguments, I felt like he was presenting his personal opinion and not representing the opinions of the students,” Bray said.

Hammond said it was never his goal to upset people, and he sees this as an opportunity to make a statement about important issues, such as challenging white supremacy.

“If I was put on the committee, then I have a responsibility to strongly advocate for what I believe, balancing my view with the public’s view,” Hammond said. “My position has always been to fight for the best quality name … I will never not acknowledge the majority of the public’s views .. .but I can’t say I would have done anything different in my position because I wouldn’t have.”

Some students found it frustrating that it seemed like their responses didn’t weigh as heavily in the decision.

“Honestly, I think that it is stupid that the recommended name wasn’t Midtown, the one that got the majority vote,” sophomore Cecilia Rice said. “I thought the whole point of letting us vote was because we (the students) should be able to decide or at least have the authority since it’s our school. It’s like they gave us the power to decide and then just switched it up.”

Kinard, representing the Council of Intown Neighborhoods and Schools (CINS), said she decided how to cast her vote based on her constituents’ overwhelming support for Midtown. Kinard said given the extended process, the outcome was frustrating.

“It would be really easy with a short process to say, we’ve heard from the community,” Kinard said. “But lengthening the process gave us time to really know that we were, individually within our communities, doing the outreach to make sure we were getting the input. So it’s frustrating given that we had that time specifically in order to get community feedback, and then seemed to, even though that feedback went one way, vote majority the other way. It was frustrating.”

For Grady cluster parent Audrea Rease, Wells is a personal hero, but she said by naming the school after Wells, the focus is still on Henry Grady.

“I feel that to name a school after her is still censoring Henry W. Grady in a way because her name was chosen as a counterpoint to him,” Rease said. “She was chosen because she’s his polar opposite … I don’t like to see her kind of being used in that way. And I don’t like that he will still factor in a big way in the ongoing story of this school, mainly because he’s always going to be part of the explanation for the renaming of it. You can’t talk about why the school was renamed to Ida B. Wells without talking about him. You can talk about why the school was called Midtown High School.”

Rease started a petition to “vote no” on the committee’s recommendation because it “does not appropriately reflect broad and overwhelming community input.” The petition argues that the current recommendation is “skewed and inaccurate” and “feels ‘reactionary.'”

“I thought that perhaps doing another petition would encourage the board to vote no to this name,” Rease said. “What I hoped they would do would be just to go back and pick up, pick some other options. Whatever the errors and flaws and criticisms in the process have been so far, move forward in such a way that does not replicate those same issues, and hopefully, pick a name that’s not so polarizing to the community or that doesn’t feel so disconnected to the community.”

Looking Forward

Hammond, Grant and Kinard all said the committee believes Ida B. Wells High School will be an appropriate namesake that represents the Grady community.

Some students have come around to support the recommended name. While senior Re’Onna Vines supported the Midtown name during the renaming process, she recognizes the historical importance of renaming the school after Ida B. Wells.

“I initially felt there was no purpose in the community vote if it wasn’t acknowledged; however, I completely understand the significance of going from a white supremacist person as the face of our high school to an all-inclusive civil rights activist who is a Black woman,” Vines said. “I was pleased with the progress and love that the legacy of our high school is about to change.”

The committee’s decision cemented the recommendation it will make to the school board, which will take the final vote Monday, Nov. 2. While there are no other formal opportunities for community input, community members can still reach out to board members and provide feedback for this specific name change. Additionally, stakeholders can also provide input on the name change process, as a whole, in order to influence the way future name changes are decided.

“It’s important for people to give their input, and to make their voice heard,” Kinard said. “The process isn’t over and the board still has to vote. So, if people feel like their voice was not heard, there are other avenues to share … there’s multiple ways that people can make their voice heard. It could be a change in policy with the board on how we go about this renaming or it could be making your voice heard, to the board before they take a vote in November.”

To find your Board representative and contact info for all Board members, use this link.

Additional reporting by Dana Richie, Jamie Marlowe, Aran Sonnad-Joshi and Marcus Johnson

![In his AP Comparative Government and American Government [Civics] classes, Rhodenbaugh surveyed his students on their opinion of the school name.](https://thesoutherneronline.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/AOBMTT56ylAQDAyv5OcJ66jtJardVgcasZEF6MLL-300x123.png)

Carleen Crawford • Oct 28, 2020 at 12:03 pm

So all that input was for naught? The name should not be changed in the first place and really., why Ida B Wells? In a few years someone will find a problem with that name, too. As a Grady grad I am sad.

Bobby Dennis • Oct 28, 2020 at 7:19 am

I am a Grady High Alumni attended Grady 1976-80. I don’t feel the board reach out to the Alumni to get our in put on the name change. I grew up in the Grady area as well the old 4th ward, Grady Homes, Wheatstreet Gardens, Morningside, Techwood Homes,Bedford Pine were all parts of the Grady High areas as well but the area that was mention was Midtown. I think the renaming Committee of mostly students. Should reach out to the Alumni as well. Dr. Thomas Adger was a very good choice because of the history and what he meant to the Community and the Alumni. I have family that attended Grady and graduated from Grady as well as alot of Alumni. I felt that the Alumni should have more say.