Silver lining: special education adapts to virtual learning

Special education teachers adapted students’ Individual Education Plans (IEPs) to fit virtual learning to ensure that students with special needs continue to effectively learn.

October 5, 2020

Recognizing that online school lacks the educational and social opportunities provided by traditional, in-person school, Atlanta Public Schools plans to bring some students with special needs back to campus as early as Oct. 26.

“Hopefully, as we move forward, we can find a way to bring our special education children back to school because we know that they really need to have these more tangible resources available to them,” said school board member Michelle Olympiadis.

In the second phase of APS’s reopening plan, students with special needs have the option to return to face-to-face instruction in three weeks or continue virtual learning. The district’s return to in-person learning, however, will be contingent on community spread of the coronavirus.

“We created a strong plan rooted in science and data with clear check points based on guidance from the Georgia Department of Education and the Georgia department of public health and recommendations of local, state and national public health officials,” said APS Superintendent Dr. Lisa Herring We continue to maintain a focus on the accuracy of the information and the guidance we receive.”

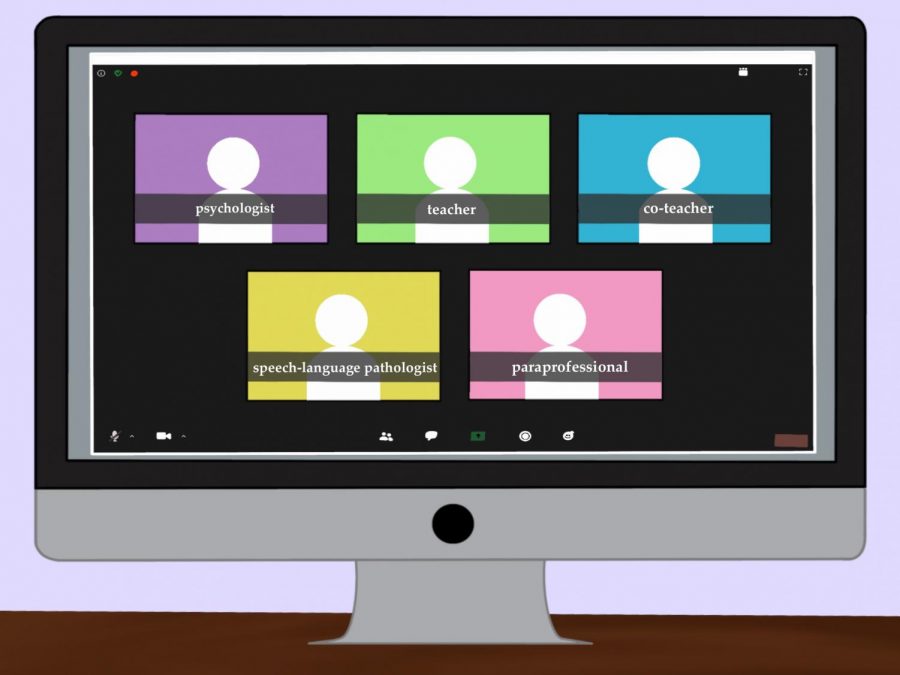

The Grady special education department took many steps to acclimate to online learning. Teachers and paraprofessionals came up with innovative and creative ways to transfer students’ Individual Education Plans (IEPs) to fit the virtual environment, ensuring that students with special needs continue to receive necessary instruction and resources.

“We’ve done a lot of discussion with both parents and students, deciding what is best for them and what struggles, especially if they were students that we had last year, we take a look at areas of struggle specific students may have had or areas in general,” Jessica Chiddister, special education lead teacher, said. “We tried to problem-solve for those before we started the school year. We’re remaining in constant communication with both parents and students to see what’s working and what’s not.”

Each student with special needs attends four virtual classes each day, receiving instruction in a full class, small group or one-on-one format, depending on need. Students are still finding ways to learn, despite the non-traditional class structure.

“Overall, I feel like most students have been participating well, and they’re adjusting, as well,” Chiddister said. “It’s been an adjustment for everybody, and I’m proud of how flexible our students have been.”

Special education teacher Mary Gossett said many students have adapted to virtual learning.

“We’ve seen a lot of progress with the students who are able to log in every day,” Gossett said. “We do have some students who don’t, but [for] the students who are logging in every day to their classes, we’ve seen significant improvement.”

Some teachers go beyond instruction to aid students. Speech-Language pathologist Phoebe Chung is helping special education students solve their technology issues.

“In many ways, I am the person who has the luxury of spending one-on-one time with a student to help them go through all of that technical stuff so that they can access the rest of their classes,” Chung said. “So, I just feel like on top of what we normally do, that has fallen onto me.”

Chung credited a smooth adjustment to virtual learning to planning. She noted that teachers already had a chance to ask questions and set everything up virtually before the school year began.

Dorothy Rehg’s sophomore daughter Katherine Rehg has Down Syndrome. She said online school has had its ups and downs, especially last spring when school first became virtual. However, she was impressed with the school’s planning for the fall semester, which exceeded her expectations.

“Last year, when they went virtual, I basically sat with [Katherine] the whole time and did all of the work and things like that,” Rehg said. “This year, I’m not able to do that. I guess it surprised me that her teacher and paraprofessional could actually help her work through problems so she didn’t need someone sitting right next to her.”

However, Rehg emphasized that no virtual instruction comes close to the one-on-one social interaction that came with in-person education.

“She looked forward to interacting with other people, so this was a little bit harder,” Rehg said.

Olympiadis said virtual learning has had some downsides. Her son, Phaethon Constantinides, misses seeing the friends he made in his special education class and all of the other opportunities that came with in-person education.

“He misses the community-based instruction where they go out in the community and go to Walmart and go shopping, or they do work in the community,” Olympiadis said. “I know he misses that, and that’s just something we’ll hold off on until the environment is better.”

However, Constantinides has enjoyed virtual learning. He said he likes the small-group virtual classes, as well as his consumer skills and multicultural literature class. Constantinides has taken the new technologies and virtual situation in stride, Olympiadis said.

“I honestly think [Constantinides] is a bit of an anomaly; he really likes it,” Olympiadis said. “He gets physical support at home, and we carve out that time to make sure that he gets what he needs. Overall, for him, it’s been a very positive experience.”

Rehg said her family is treating the virtual environment as a learning opportunity, and Katherine has done a great job adapting.

“I’d like to try and give her the independence,” Rehg said. “That’s part of it. She needs to be able to follow a schedule and be able to get on her own. I guess, in some ways, by giving her more of a challenge, the virtual learning has helped her to maybe rise to that challenge.”

Rehg is cautiously optimistic about the return to in-person education. Katherine was born with a congenital heart defect and had to undergo heart surgery when she was 2 years old, so Rehg wants to make sure Grady implements proper health protocols before the return to in-person classes.

“I think it would be good to get some time in as long as it’s done in a safe and controlled way,” Rehg said.

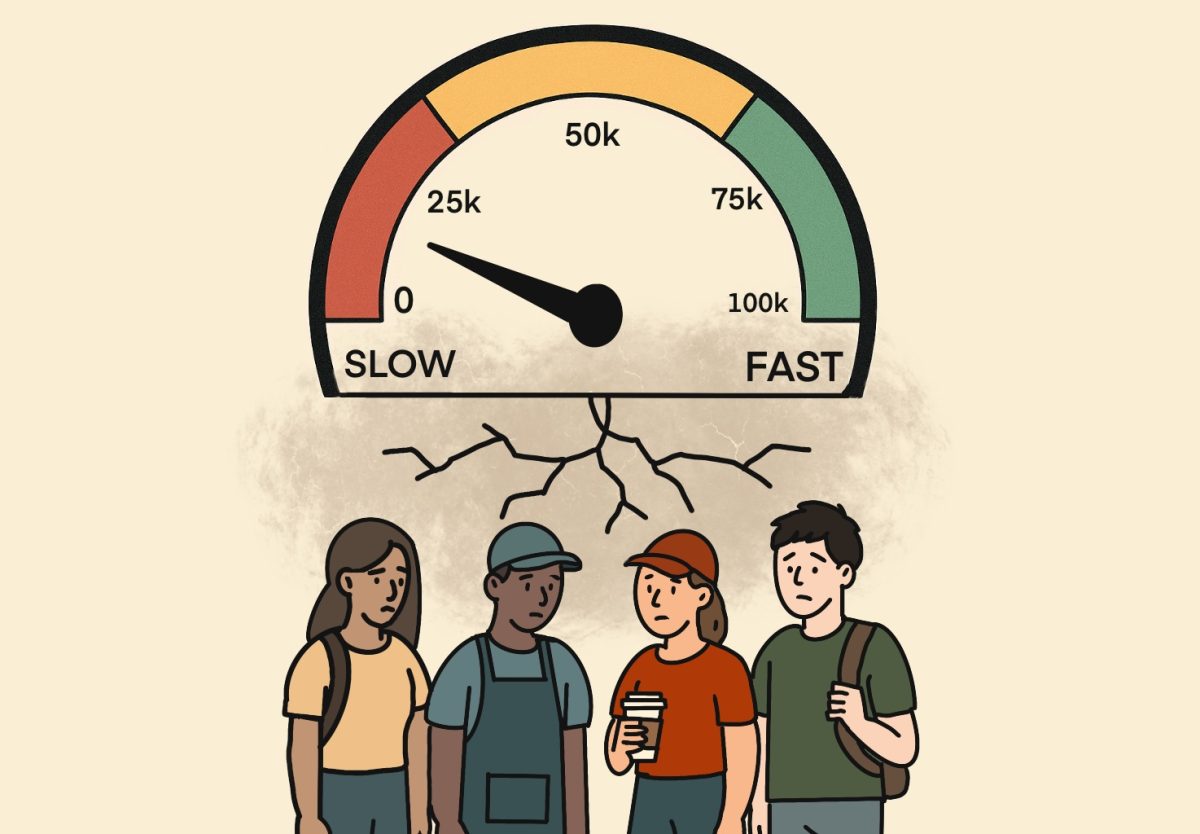

Virtual learning has complicated the process to identify special education students. Normally, a teacher, parent or administrator submits an evaluation request after observing a student who exhibits signs of a possible disability. Now, observing a student in their natural environment isn’t possible.

“Doing an observation at this time would be hugely problematic,” said Grady Cluster psychologist David Hosking. “In the virtual world, that kind of observation will be really difficult for a third party to do … we will have to rely even more heavily on teachers, parents and students themselves to supply us with those anecdotal reports.”

Hosking said Zoom breakout rooms help teachers accommodate students with learning disabilities. For instance, if a student with dyslexia can’t read as fast as required by the classroom’s procedures, that student can join a breakout room with a co-teacher to receive time accommodations and one-on-one assistance.

There has been restricted accessibility to medication for students with special needs during the pandemic, Hosking said.

“That’s a real issue,” Hosking said. “All we can do is try to assist students as best as we can with whatever we can in this virtual world.”

After staring at a computer screen for nearly five hours daily, students requiring special learning accommodations may not have the energy to seek Grady’s tutorial assistance, Hosking said. Gauging students’ needs and offering realistically accessible support is difficult for Hosking and other student support specialists.

Despite the challenges, students, parents and teachers are continuously working to improve virtual learning to ensure it provides the support and instructional quality special education students would receive on campus.

“We are trying to build the plane and fly the plane while we’re in the air,” Hosking said. “We’re trying to find the best methods to reliably and validly assess and understand student needs.”