The Deadly Spread of COVID-19 Misinformation

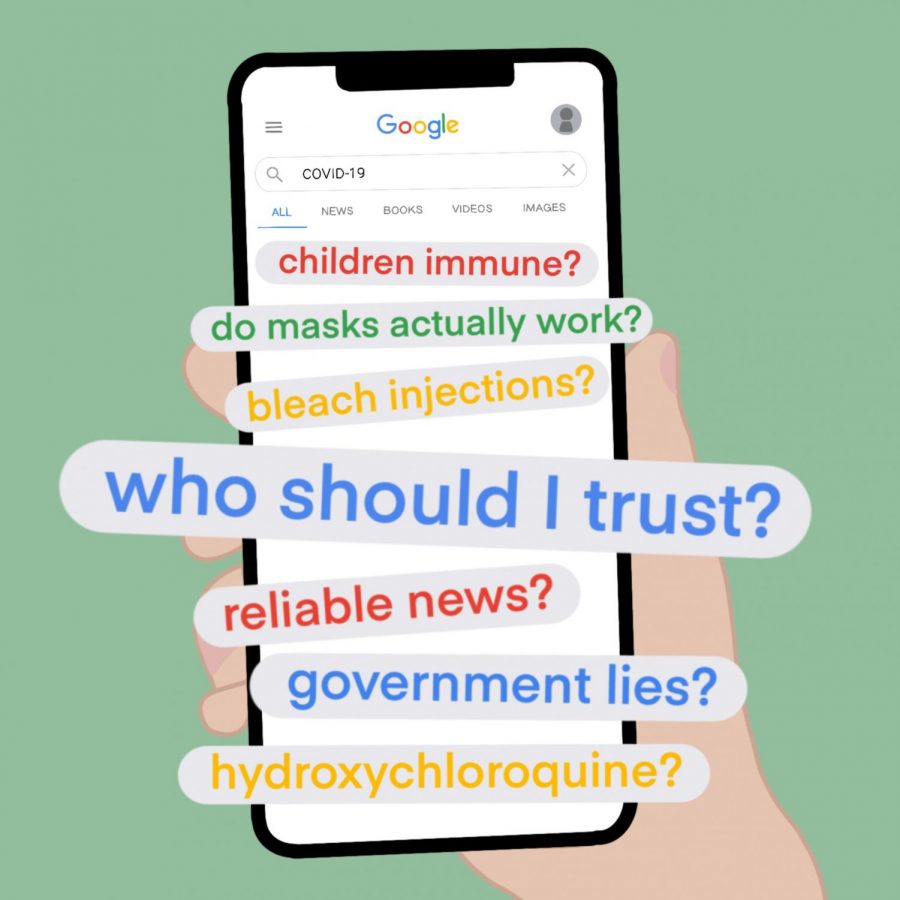

With dubious COVID-19 facts flying at you from social media, medical professionals, teachers, nutritionists and the government, sometimes, it’s hard to tell what to trust and what not to trust.

In March, when the COVID-19 virus “suddenly” appeared and rocked the world, information about it started popping up, too. No one knew anything about this mysterious virus: not scientists, not researchers, not the general public.

It’s frightening, fighting a war with a tiny, invisible enemy with whom we have absolutely no information about. Since then, research discoveries have been made, allowing us to know how to protect ourselves against the virus more effectively. But with the spread of new information, came the spread of misinformation.

The World Health Organization (WHO) calls our situation an “infodemic”: an overabundance of information that makes it hard to know which information to trust and how to navigate the choppy waters of misinformation. We’ve all seen claims about the COVID-19 virus that simply don’t make sense: children are immune to the disease, it doesn’t hurt you if you’re not immunocompromised, masks don’t do anything and are just a ploy by the government to control us. With dubious facts flying at you from social media, medical professionals, teachers, nutritionists and the government, sometimes, it’s really hard to tell what to trust and what not to trust.

Take the hydroxychloroquine debacle. A Twitter account shared a post about the benefits of using the anti-malarial drug hydroxychloroquine to prevent the COVID-19 virus, prematurely citing a study with a small sample size. The next day, it was featured on Fox News, and soon after, President Donald Trump spoke about the drug’s “strong” potential and promoted its use at a White House press conference. Hydroxychloroquine doesn’t help to prevent an infection caused by the COVID-19 virus, but it is used to treat patients with lupus and arthritis. After Trump raved about its benefits, there was a nationwide shortage of the drug, as people began hoarding it for treatment. Arthritis and lupus patients’ lives were put at extreme risk after the misinformation spread so far, so quickly.

Many have been downplaying the virus’s effect and turning to conspiracy theories to navigate the situation. A March 2020 University of Miami study found that, out of a random sample of around 2,000 adults, 31 percent believed the virus had been purposefully created and spread by the government. Twenty-nine percent of respondents believed that the virus had been exaggerated to damage President Donald Trump’s reputation.

Social media further aids the misinformation problem. As people spend more time at home, they spend more time on social media looking at information about the pandemic. Confirmation bias can take hold, as people are more likely to seek out and share posts that line up with their personal beliefs. More time on apps means more time looking at posts that confirm your beliefs again and again, nudging your beliefs and skewing your perceptions further and further until you start seeing and believing false information. If you already don’t like the idea of wearing a mask, and you see someone on Facebook discuss how they think masks don’t do anything, you’re more likely to begin believing that yourself. This creates another vector for the rumor to spread and creates more risks for spread of the virus.

One way the infodemic’s spread could be lessened is stricter policing by social media companies. Currently, Facebook and YouTube are taking down posts with misinformation, and Twitter and TikTok are putting warning labels on posts with false information. However, according to a study on misinformation concerning the COVID-19 virus by Reuters and Oxford University, companies could be doing a much better job. The researchers tracked posts with false information relating to the virus, and on Twitter, 59 percent of posts containing false information remained up or without warning labels, compared to 27 percent on YouTube and 24 percent on Facebook. Though fact-checking the millions of posts on each of these sites is challenging, these companies have to do better.

It’s likely that even if you try to only get your media from reputable sources, you’ll see something that’s false. So, what can you do to try to curb the false spread of information? If an article or fact seems dubious or makes you feel a strong emotion, fact-check it. Ad Fontes Media has a chart that ranks various news sources’ media bias and fact reporting, which is a helpful tool to check if a source is trustworthy. Snopes is a fact-checking website that constantly updates itself to be up to date with popular social media posts.

The most important thing you can do to slow the spread of the “infodemic” is to become a thoughtful consumer of media. Though it can be entertaining to look through news and social media, it’s necessary to remember how quickly false facts can spread and that tweets and stories are not news sources. Staying vigilant about your consumption and fact-checking constantly will stop misinformation spread and potentially save lives.

Anna Rachwalski is a senior and this is her third year writing for the Southerner. Outside of the newspaper, she is president of the Quiz Bowl team, is...