Examining the legacy of Henry W. Grady: Q & A with journalism historian Dr. Kathy Roberts Forde

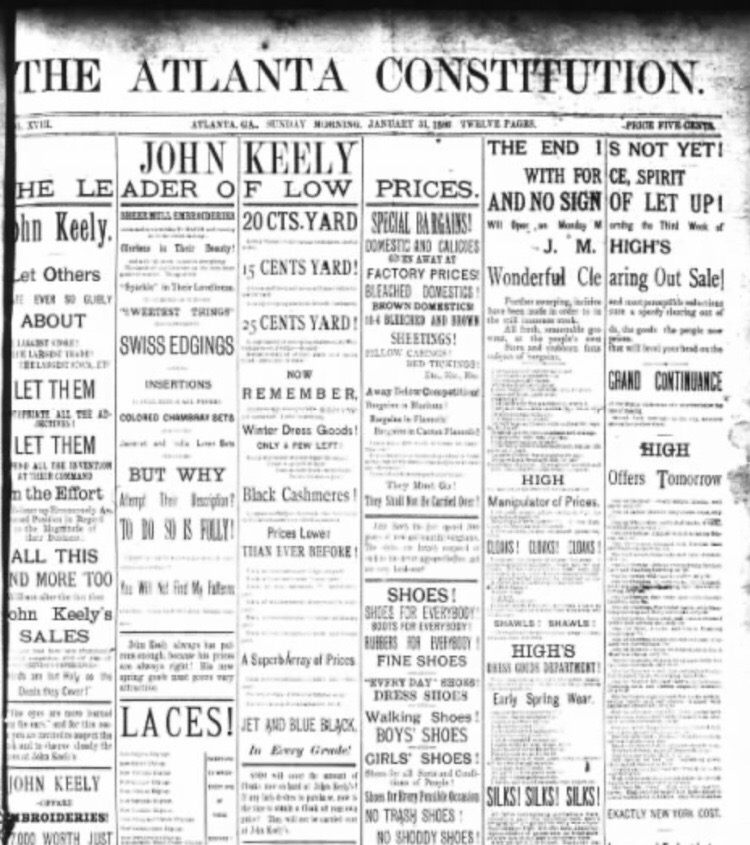

Atlanta Constitution via newspapers.com

This is the front page of the Atlanta Constitution on Sunday Jan. 31, 1886. A significant part of Henry W. Grady’s legacy in Atlanta is his contribution while being owner and editor of the Atlanta Constitution. Dr. Kathy Roberts Forde emphasized that, like many newspapers in the South during the 1880s, the Atlanta Constitution served as a mouthpiece for the Democratic Party.

August 15, 2020

Dr. Kathy Roberts Forde is an American journalism historian and professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. She specializes in U.S. journalism history, African American freedom struggle and the press and literary journalism. Currently, Dr. Forde is the lead co-editor of a book entitled “Journalism and Jim Crow: The White Press and the Making of White Supremacy in the New South” that is scheduled to come out in early 2021. As a part of a series of conversations with experts on Grady’s background, The Southerner sat down with Dr. Forde to discuss his legacy, journalism and political beliefs.

Based on your research, how would you describe Henry W. Grady?

A lot of the historiography on Grady discusses him as a great newspaper editor of the South, as an important economic builder of the city of Atlanta, as well as someone who was deeply committed to the betterment of Atlanta socially, economically and business-wise. [They portray] that he was a great speaker, a great orator, who spread the ideals of the New South not only across the south but across the nation. A lot of people like to point out his interest in baseball and bringing baseball and doing a lot of civic organization and activity for the city of Atlanta. It’s not that those things aren’t true, but it’s that it is a very partial understanding of who Henry Grady was. Another very significant part of his story is that he was a key architect and promoter, in my historical telling, of white supremacist political economies and social orders in Georgia in the 1880s, but not just Georgia because his ideas he promoted throughout the South and across the nation in his New South speeches and the stories he told in the Atlanta Constitution.

There’s more to say though, too, which was that he was a kingmaker. He was a political kingmaker in the state of Georgia. In 1880, he became part owner and managing editor of the Atlanta Constitution. At the very same time, he became the political mastermind of Georgia state politics and the Democratic party, where he was part of what was known as the Atlanta Ring, [which included]] Gordon, Brown, and Colquitt. These three men rotated through the governorship and the US Senate seats for the state of Georgia. All three men were involved in convict leasing. All three men, particularly Brown and Colquitt, made money [from convict leasing] and James English, who was the police commissioner in Atlanta and seen as this peripheral figure of this Atlanta Ring. They were all deeply involved in the convict lease… In this way, you had thousands of Black men, women and children in the South caught up in these nefarious, brutal labor schemes that profited elite white people and built tremendous affluence among certain families. Georgia was infamous, by the way. Atlanta has a terrible history. When you read these details, it is disturbing in the extreme. Henry Grady protected this. He himself didn’t lease. He wasn’t involved in these industrial schemes, but he was involved in making sure they continued…Grady knew all about convict leasing. He reported on it all the time…Grady defended the system and the Constitution throughout the 1880s.

Beyond that he spoke, as you know in his New South speeches, about the supremacy of the white race. A lot of historians will say Grady was a mild racist for his time period. Well, Black southerners didn’t see it that way. There were millions of Black southerners at the time. It’s a way of people saying today he was a mild white supremacists. Well, white supremacy was what it was. Yes, it was widespread all over the South at the time, but it had to be built. He was a key builder during a pivotal moment post-Reconstruction in the 1880s.

How would you describe his political opinions in the context of the time period?

The Democratic party during that period was not a progressive party. They certainly weren’t racially progressive at all. They might have been progressive in terms of notions, at the time, about industrialism and about the South needing to industrialize and needing to advance its economy not only on agriculture. Beyond that, I don’t see the Democratic Party, which was the party that Grady was deeply involved in, as a progressive party during the 1880s and 1890s. I simply don’t buy that notion. C. Vann Woodward is one of the biggest historians of the New South era, and even mid century, he had overturned the idea of the New South people being progressives. He really sort of punctured that. Serious historians by and large, very few would think of Grady as a progressive…Of course, Black intellectuals of the time, almost all of whom were journalists, opposed Grady. They named it straight out what he was up to. I find it really interesting that people today are so hung up on understanding Grady in this particular way. We don’t know if he was or wasn’t in the [Ku Klux] Klan. I have evidence from an article he wrote in the Rome Commercial, a newspaper that he wrote for, where he writes a letter to his ‘brothers in the Klan.’ The historical record suggests that he at least earlier in his life was quite sympathetic, if not a member.

How did his political opinions impact his journalism?

He was very much involved in Democratic Party politics behind the scenes and out front. He conducted a lot of political campaigns. He was the campaign manager for Gordon, Colquitt and Brown as they were cycling through governorships and US Senate seats. He often conducted their campaigns, and then he wrote about it in the newspaper and supported their campaigns in the newspaper. The newspaper also covered up information that was damaging to his little group of politicians that he was keeping in power. He prosecuted his politics very clearly through the newspaper. It was basically a mouthpiece for the Democratic Party leadership, and he was a part of that leadership in the state of Georgia.

Was journalism like this common during the time period?

By the time we get to the 1880s and the 1890s, when you’re talking about urban daily newspapers across the country, in the North, the commercial newspapers had moved away from this kind of really close-knit connection to political parties. When we’re talking about the big daily newspapers in New York City, for example, that’s the era that we begin to get to what we call yellow journalism, which is really mass commercial journalism. Because the interests were so much in selling newspapers, as many as possible, so many of the newspaper editors and publishers moved away from the previous model where newspapers had been tied to political parties. This had been very much a strong model of journalism from the founding of our country. They wanted to get away from political party connections and from being overly ideological because if you’re associated with one party, then that means people of the other party aren’t going to buy your newspaper. If you can appeal to everyone and be kind of nonpartisan, then you’ve got a broader audience and more people to buy your newspaper. That was the trend in the late nineteenth century, particularly in the urban areas in the North. The South just didn’t get there. Most southerner newspapers still very much remained tied to political party interests either superficially or behind the scenes well into the early twentieth century. It’s true of other parts of the country, too, but what we’ve discovered in our research is that [for] so many newspapers in the South, the editors and publishers were very involved in party politics into the 1930s and 1940s.

I have looked at some old Atlanta Constitution newspapers and one headline read “Two Minutes to Pray Before a Rope Dislocated Their Vertebrae.” These lynching headlines were brought up in some of the name change meetings, and some were saying that Grady humorized the lynchings. Can you go more in depth about those headlines within the context of the time period?

White newspapers played a significant role in the South in normalizing lynching practices. Lynching, as you know, became a form of widespread racial terror that was used by white southerners to terrorize Black southerners and to send messages by policing the racial hierarchy and the caste system of the South. In the 1880s, lynching began to grow as a practice and then it became more and more prominent in the 1890s. From 1880 to 1920, I’d say there were about 4,000 incidents of racial terror lynchings in southern states. It’s not that they didn’t exist outside the south, and it happened to folks beyond African Americans, but it is this massive widespread practice in the South…When we look at Henry Grady during this formative period of the 1880s as the Jim Crow South is just beginning to be built, his coverage of legal hangings, which still happened at the time, but also extra judicial lynchings, which are often racially motivated and tools of racial terror, those headlines and those practices of that callous humor began to set a tone…When we look at those headlines, I think it’s also important to note that one of Grady’s former professors at the University of Georgia wrote him a letter on the Chancellor’s letterhead. This is in the Grady collection at Emory University’s Rose Library. One of his former professors wrote him a letter telling him that this kind of disregard for human life, that this kind of levity in the face of such inhumanity and this thing of hanging people…doesn’t reflect well on [Grady] and [Grady] need not to be doing this.

What do you think should be taught about Henry W. Grady?

I think a full story. We do no credit to ourselves or to the past when we don’t tell stories in their fullness and when we don’t understand historical figures and the work that they did in their fullness. It’s absolutely fine to talk about Henry Grady in terms of building Atlanta. I’m not sure he built Atlanta for Black Atlantans. In fact, I would say that if we are to understand him, we need to understand what he did to build white supremacy in the South and to limit opportunities for Black southerners in terms of access to the vote. He very much spoke against the rights of African Americans to the vote. The last speech of his life was all about how there was a problem of Black southerners voting. When we look at what he did to build white supremacy in the south and to limit opportunities of civil rights, political rights and human rights for Black southerners, that’s a huge piece of his legacy and his story.

How do you think this renaming debate fits into today’s political climate?

I think the renaming conversations are happening in a lot of different places. There are conversations happening about how we should tell our history, what it is we should remember about our history, who should be celebrated, who should not be celebrated, who should have monuments and who shouldn’t. I think it’s really important to keep in mind that when people make an argument that to change a name or takedown a monument is to erase history, that is not what is happening. What’s happening is history is being retold in a different way, and that’s important. History is a story; we’re constantly learning new information, and we’re constantly reconstructing our histories. We, in the present, can use our history as a way to learn about the past and then we hope to build a present and future that’s more just and more in line with what many of us hope are the actual values of this country: democratic values and values of inclusion and access and opportunity. When people say we’re erasing our history, I simply don’t see it that way at all. We’re deciding how we’re going to tell our history and what story we’re going to tell.

If you could tell the Grady High School community one important thing to know about the history of Henry W. Grady, what would it be?

I think what I can do is provide much more information about the historical record of Henry Grady. I hope that my research is doing that…You have to have the information in order to have an informed debate and one that’s oriented towards justice. At the end of the day, I guess I would also say that the stories we tell matter. The names we give to places matter. The monuments we put up in our public spaces tell a story about the past that means something to the people in the present. People in the present want to be a pluralistic, diverse society that’s just and racially just and just to people of all different backgrounds that’s not divided according to gender or sexual identity or ethnicity or race. We don’t want people to be excluded from opportunity. The stories we tell about the past are kind of guideposts for the now. They matter.