Forgotten Youth: when college is not your first choice

A number of factors, particularly home environment and community pressures, can impact a student’s performance in school and their lives post high school.

When 2018 graduate Peter Bowden began Grady in 2014, he lived next to a crackhouse that was undergoing renovation on Boulevard. Growing up, he saw friends jailed and even killed.

Bowden said kids around him engaged in illegal activities to make money for their families at an early age.

“They’re trying to support their parents, their families, whoever they have in there,” Bowden said.

An underclassman, who wishes to remain unidentified to protect their identity, said when they used to deal drugs such as marijuana and cocaine, they “lived in paranoia.” They say their friends involved in the business today live in communities that normalize such a lifestyle.

“A lot of the people that I mess with live in East Atlanta, but some live by Parkway and Boulevard and all that, so some of them are involved in drug businesses,” the underclassman said. “Some people have robbed them or tried to kill them.”

Bowden said these students may bring illegal activities and a negative mentality to their school environment, which can hinder their ability to learn.

“You never really know what’s going on with somebody until you see them outside of school,” Bowden said. “And I can say probably a lot of students that went to Grady for a while, who aren’t going there anymore, who have just dedicated their life full-time to making a living out of … organized crimes, selling drugs — maybe theft, you know, things that will make you quick cash but aren’t really good to keep doing in the long run.”

For these students, life post-high school may be unpredictable, and going to college might be the last thing on their minds.

HOME AFFECTS SCHOOL

“Get to class.” “Take those headphones out.” “Keep it moving.” In the halls, teachers and administrators encourage students to engage with their school setting. But their seeming disinterest might result from a difficult home life.

Athletic booster club president David Boone, who grew up on the south side of Chicago, says a student’s community environment can affect their school lives.

“If you are in a household that is loud, [has] conflicts, arguing and things of that nature then you don’t get rest, and if you don’t get rest then that certainly goes back to your attitude, how you come to class, whether you are fatigued, whether you are alert, how you feel about your situation in general,” said Boone, who is also a Grady parent.

A 2015 study by University of Wisconsin researchers published in the Pediatric Journal of the American Medical Association found that students who grow up in poverty may have delayed brain development and significantly less academic achievement than their wealthier counterparts. The study reported that by the end of elementary school, students receiving free lunch were three times behind their peers, academically, and by the end of high school, those same students had on average a lower grade point average by 1.7 points.

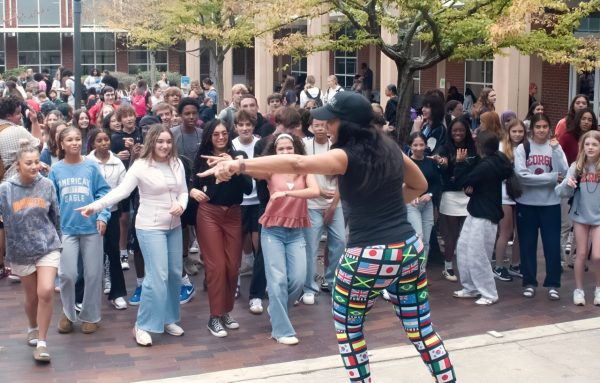

Calvin Colquitt, a Class of 2000 graduate, started a counseling program called “Defying the Odds” in 2005 to help inner-city Atlanta teens who struggle with poverty. Growing up, Colquitt attended an elementary school in a neighborhood where the graduation rate was below 50 percent.

“I grew up in an area where I didn’t see people go to college, graduate and earn enough money to sustain themselves, so I never saw successful people that went to college,” Colquitt said. “I saw successful people doing illegal things. So what happens is you are naturally attracted to that, because you’re like ‘I don’t want to be poor, I’m tired of being poor.’”

His hands-on work with underprivileged teens allowed him to physically go into kids’ homes and find a solution to mitigate their problems at home. Colquitt saw physical abuse, drug abuse and cases of extreme poverty: situations that he saw growing up.

“If I was beaten because my dad was drunk or my mother couldn’t pay the bill, and she beat me, I [would] still have to go to school in the morning,” Colquitt said. “Or if I had bullets shot through my house that night that traumatized me and I couldn’t sleep, I [would] still have to go to school.”

Although Colquitt is no longer involved in the program, he says oftentimes kids cannot separate their home lives from their school experiences, which can create tension at school that administrators may not understand.

“All it would take is one small trigger at school and then the fact that they just got beat, molested, raped, didn’t have food to eat, saw their parents fighting that spilled over,” Colquitt said.

Poor academics can be linked to poor behavior, according to Caren Cloud, program administrator at the Fulton County Juvenile Court. She said students who pass through the court, mostly between the ages of 13 and 15, struggle with school.

“A lot of it is they’re just so far behind that the ability to catch up is just not there,” Cloud said.

Atlanta Public Schools and Grady use suspension and expulsion as punishment for students who commit certain offenses. In September, a student was arrested for bringing a handgun on campus. But student support advisor Patricia Maxwell says removal from the educational environment, such as suspension or expulsion, is the beginning of a long road of problems that will continue to plague students through adulthood.

“Any time we remove students from the instructional environment is detrimental,” Maxwell said. “The challenge for schools is to balance the imperative of keeping students safe with keeping students in school.”

LIFE AFTER HIGH SCHOOL

A difficult home life, poverty and potential behavioral issues make planning for future success more difficult.

Principal Dr. Betsy Bockman says students who lack encouragement at home may struggle to begin the complex college application process, one of essays, financial aid forms and test-taking.

“That’s too much for people that are just trying to get food, and for kids that don’t ever sit down for a meal,” Dr. Bockman said.

Some students may need or prefer to take an alternate path. Although junior Jaxon Stewart plans to attend college, he has friends and knows people who plan to jump into the workforce or adopt trades. He thinks that alternate career paths are not encouraged at Grady.

“I feel as though [the administration] tries to send us to go get a higher education and then go get a job not necessarily realizing that this academic stuff isn’t what a lot of these students need,” Stewart said.

He feels that the administration can begin to support students by offering classes that help students prepare for trade jobs.

Geometry teacher Laketa Blue agrees. She said her own high school supported students who didn’t plan on getting an undergraduate degree.

“What [Grady is] missing is that being the first to graduate from high school is a lot,” Blue said. “So getting students to that point, who we know are not going to college, is more innovative than trying to push somebody into something they don’t want to do.”

Assistant Principal Raymond Dawson acknowledges the school does not do a sufficient job at simulating the real world and supplying students with the life skills necessary to succeed beyond college or university. Dawson argues that although Grady attempts to mimic society and provide students with avenues outside of college, he believes that these attempts are not enough.

“We give students a diploma, a dream and a lot of rhetoric,” Dawson said. “The schools, at one time, offered not only academic classes and academic promise, but it also offered skills. What you were doing was preparing young people with skill sets who may not find that in a college or university, because that’s not who they are.”

School-based community behavioral specialist Madison Kosater interacts with Grady students and parents on a weekly basis. She says that one of the most important things the administration can do to help students is to be attentive to individual students’ needs.

“[Grady administration needs to] make sure that a student is getting what they want out of school, whether that’s college, or going into a vocational program,” Kosater said. “Just something that they’re passionate about.”

Dr. Bockman says she encourages students who are not applying to college to adopt a trade or skill and consider going back to college later. She has set up internships and summer jobs for students with Parrish Construction, which is currently renovating David T. Howard Middle School and will build Grady’s new addition next year.

“College at [age] 19 is not the only thing,” Dr. Bockman said. “There are other paths, first.”

She encourages conversation with students and tries to build trust to help them best. This year, she moved Maxwell to an office in the media center, where she can easily engage with students.

“[We’re] trying to get more people on the ground that can just listen to kids and get them into certain areas,” Dr. Bockman said.

COLLEGE AS A WAY OUT

However, some students, like sophomore Ja’Quez Wright, are motivated to attend college, viewing it as an escape from their difficult home life.

“College is my only way out,” Wright said. “I just want to succeed after everything that I’ve been through in life. I haven’t always had things handed to me.”

Senior Demario Worthy plans to go to college despite its financial barriers. When Worthy realized that it was time to get serious about college, he reached out to his college advisers to apply to schools. He did so while juggling high school classes, dual enrollment and two jobs.

“Not too many people in my family had the experience of going to college,” Worthy said. “I don’t come from a privileged home. I realized no one is going to give me what I need, so I had to find a method and reach out on my own.”

Worthy says some seniors don’t take advantage of the programs and resources provided for them. Grady offers help through its College and Career Center and college advising, led by Amber Jones and Abby Poirier. Atlanta Public Schools offers the Achieve Atlanta Scholarship to both college and technical school-bound students.

“We don’t know about certain things because we don’t ask,” Worthy said. “[Students] shouldn’t give up. If they really want to go to college, they should make an effort.”

Jones and Poirier have met with almost every senior this year, and they say most students, even those from difficult backgrounds, plan on attending a four-year college or two-year technical school. They say a “handful” of students say they don’t plan to apply. While some may be opposed to college at first, they may change their minds senior year.

“Grady has a very strong college-going culture,” Poirier said.

Still, college is not for everyone, and students who struggle at home have more difficulty than others when planning for the future.

“There are kids here that are outliers, and they aren’t being prepared for life which is why they are getting in trouble,” Stewart said. “We say ‘individually we are different, together we are Grady,’ but … we need to utilize the creativity and diversity that each student has.”

This is Aaliyah's first year writing for the Southerner. When she isn't writing, she is either running hurdles on the track or practicing her closing arguments...

Kamryn Harty is excited for her last year on The Southerner staff! She is a Co-Editor in Chief and a member of the class of 2021. When she’s not writing,...

Katherine Esterl is a senior. She spends her time rehearsing plays, building houses and watching Frasier.

Contact

[email protected]

Yolanda Windham • Nov 18, 2019 at 8:48 am

This was a good read. Great Job!!

Betsy Bockman • Nov 15, 2019 at 1:00 pm

well done and much needed.