Pianos for Peace

Atlanta-based organization aims to unite community through music

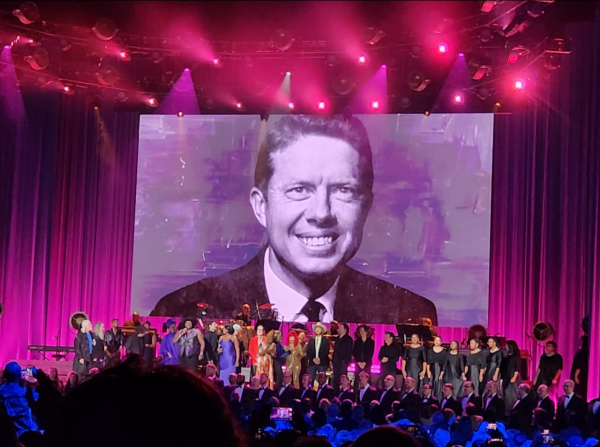

Photo courtesy of Malek Jandali

A SYMPHONY FOR PEACE: Pianos for Peace is an Atlanta-based organization that displays over 50 painted pianos from places like the BeltLine, MARTA stations, and the airport from Sept. 1-21, later donating them to schools and nursing homes across the city.

Composer and activist Malek Jandali performs in a peaceful demonstration in front of the White House in Lafayette Park in July of 2011. Playing “Watani Ana,” or “I Am My Homeland,” Jandali speaks out against the atrocities of the Syrian civil war. Shortly after, his parents are severely beaten in their home back in Syria.

“I performed for freedom and supporting the children of Syria as an American artist,” Jandali said. “Within 72 hours my dad was handcuffed and forced to witness the torture of my mother in their bedroom. My mother was screaming and said ‘Why are you doing this?’ and they told her ‘Because of your son’s music.’”

Ever since the attack on his parents, music has taken on a whole new meaning for Jandali. From the creation of pieces about global conflicts like “The Silent Ocean” to founding the non-profit Pianos for Peace, Jandali has combined his musical abilities with a passion for world change to impact his community.

“It’s not a joke,” Jandali said. “For the head of state, the dictator, to make make an executive decision to send ‘the police’ to attack your mother in her bedroom. Music is powerful, it can impact people. That’s where Pianos for Peace came along, I said if I can music can impact people in such an ugly way, maybe we can do the opposite.”

Founded in 2015, Pianos for Peace is an Atlanta based organization that aims to spread peace through music. From Sept. 1-21, the organization placed 50 painted pianos around Atlanta, from MARTA stations, to the BeltLine, to the airport, as a public arts festival. The pianos were donated to schools and nursing homes throughout the city, with the festival ending on the International Day of Peace.

“I think that music touches people in a way that is just different from visual arts,” said Michael Hobbs, who became a part of the Pianos for Peace team after meeting Jandali through Georgia Lawyers for the Arts. “Visual arts have incredible capacity to touch people in their lives, but I think there is something with music that from a very young age we remember music … I think Pianos for Peace [puts] people in places from they haven’t been in the past as recently, and it’s immediate. It takes only a second or two for it to really touch that part of their lives. That’s pretty amazing … A lot of public art can be ‘don’t touch,’ and this is the opposite.”

Grady became involved with the organization after being chosen to paint one of the public pianos. Covered in geometric patterns and branded with the Grady logo on the front, advanced placement art students spent time after school designing the piano’s final look.

“It’s a really cool thing to do in such an urban area,” said Assata Norment, one of Grady’s artists that helped paint the piano. “The fact that we got to contribute to that is fantastic … Artists have been involved in this project, but I think that it’s unique that Grady students got involved, and that we get to leave something impactful like this.”

Pianos for Peace is part of a larger movement towards unity through public art. From New York to Rome, public pianos have become a staple of subways and street corners. David McGough travels globally to perform on street pianos, and despite the limited pianos on display at the beginning of the festival, came to Atlanta to play with Pianos for Peace.

“There’s sort of a movement world wide to put pianos in public places,” McGough said. “You meet some strange folks when you sit on a piano and play it in the street. I think that the merger of the art and the music makes a pretty powerful statement … What it really does is make people stop on the street and come together and go ‘Oh, I know that song,’ or ‘Let me play one for you, do you remember this one?’”

The organization brings together schools, community centers, and individuals to design and paint the pianos. Each piano is given a booklet, telling the reader that it is theirs to play, as well as sheet music to songs and the organization’s story in several different languages. Everyone from children playing “Chopsticks”, to passersby playing Beethoven, to even dogs can be seen interacting with the pianos.

“When they are playing the piano you can tell it touches some curve of chord or note in their own lives where they remember a different time or place, and we hope that gives them hope to come home to that place again,” Hobbs said. “It’s not limited as to who it touches, I think it really expands past age, race, economics, and I think there is something really magnificent about something that can touch people in that way across the spectrum of experiences in Atlanta.”

Amidst the events of Pianos for Peace, Jandali is, at his roots, is a composer. Born in Germany and raised in Syria, Jandali draws much of his artistic and activist inspiration from his early encounters with music.

“When we moved back to Syria we didn’t have a music school in my city, so it was a challenge to maintain my musical education,” Jandali said. “I used to travel two hours for my piano weekly lessons with my mother until I reached high school and I started travelling on my own, and then I got accepted into the music conservatory. I recorded a cassette tape of my repertoire and sent it all over to my birth country [Germany], to [the United States] and landed a full scholarship in the United States. And that’s how I came here.”

He uses his diverse background to combine elements of music from around the globe to unite people. Jandali even notes differences between composition in the East and in the United States.

“I am a global citizen, so you just absorb all of this culture,” Jandali said. “It is how you behave, what you eat, what you compose, what you listen to and what you dress in … I get all of these modes, or we call them ‘makams’ in the East, and the are different from the scales which only have majors and minors, and with the makams we have so many other things. We [in the US] only have flats and sharps, and we have half-sharps and quarter tones … I consider myself very lucky to have all of these cultures embedded in my soul and in my music … because I am trying to preserve the beauty of my culture at the very moment it is being eradicated.”

Jandali also cites Syria as an inspiration.

“Growing up in Syria, it’s the land that invented the alphabet to mankind,” Jandali said. “The Ugaritic civilization in Ugarit off of the Mediterranean coast invented the alphabet, the abc’s. Not to the people of Mesopotamia, but to the people of mankind. That’s their contribution to humanity.”

His compositions have become a voice, from those seeking peace here in the United States, to those facing the atrocities of the Syrian civil war.

“I was a peace activist for the kids who are being brutalized and tortured to death back home through music,” Jandali said. “I composed a song called ‘I am My Homeland,’ without specifying the name of my homeland. Some people might say ‘He is an American,’ or ‘Oh, he is a Cuban,’; I didn’t say ‘I am Syrian,’ or ‘I am American.’ I said ‘I am my homeland and my homeland is me, my love for you is fire in my heart, when am I going to see you free?’ ‘Free’ was the big word that bothered the people against freedom and peace and music.”

Jandali cites the key to impacting people through movements as timing.

“[I am My Homeland’] became a very popular song in the Syrian uprising, public, students, kids, and journalists, because it was relevant and timely. It is all about timing, if I compose it today nobody is going to listen. I have learned in life that you have to do the right thing, at the right time, for the right reasons. Then you can have an impact.”

Pianos for Peace works to create unity in Atlanta through public music. Some of Jandali’s favorite moments come from simply watching people interact with the pianos on the street.

“One story is that I saw a homeless guy, and he was hesitant to come to the piano. He wasn’t sure if he was allowed to touch it,” Jandali said. “I was observing him, and he finally decided to go and sit on that piano in downtown Atlanta, and he played Chopin’s ‘Polonaise’. When he finished, I was in tears … For these few moments when he performed Chopin, people gathered around him, he wasn’t homeless during that time.”

The man’s performance moved Jandali.

“People saw him as an artist, as a human,” Jandali said. “When he finished his performance, people started clapping for him, and he just moved. And in a few minutes after walking away, he became homeless again. And that bothered me. I was wondering, ‘How can I keep him an artist?’ That’s when we thought about the year round community program…We kept that piano in Little 5 Points the whole year round.”

Pianos for Peace has created union throughout the city. Unlikely strangers sit and tap out tunes in one of Atlanta’s largest public art displays. As I sat with Jandali in Grady’s art gallery, he noted not only the improbable likelihood of these interactions, but of the two of us meeting. We were from different cultures, different generations, and it was the piano that brought us to meet. This community connection, especially with the schools, is what he describes as vital to the organizations mission.

“We had two schools last year that built a music program because of the painted piano, how amazing is that?” Jandali said. “… It is a domino effect.”

Members of Pianos for Peace’s team hope that the organization not only impacts people through the community, but inspires people to do the same.

“If one person can start with this extraordinary dream, and then spread that out throughout the city, the question then becomes, what if each of us did that?” Hobbs said. “What if each of us brought out own ideas and our own passions and our visions, what else would be possible? … I think that’s pretty important for people to visualize change and then say ‘What can I help to do that in my own life.’”

Jandali hopes that the initiative also changes how people view music.

“Usually ‘symphony’ is like ‘Oh, symphony? We can’t talk, it’s only for the elite’,” Jandali said. “No! We are the symphony for peace, you are the symphony for peace! It’s changing the narrative about the term for symphony.”

Ever since the the creation of Pianos for Peace, Jandali has been astounded by the impact music has made in the city. From commuters taking time out of their day to tap out a tune, to schools creating music programs after the donation of pianos, Pianos for Peace has worked to create a more united community.

“It is social,” Jandali said “There’s nothing more social than making music. It takes an orchestra, it takes an audience, and it’s amazing. We are all in a symphony for peace.”

Tyler Jones is a senior in her fourth year writing for the Southerner. When she is not writing features on anything Atlanta, you can usually find her in...

Sandra Sazma • Jul 1, 2021 at 2:34 pm

Would you take an older upright piano that we would like to donate? We are in Flowery Branch GA. 30542.

Thank you,

Sandra Sazma