Tracking students eases teachers’ burden while hurting students

By Maura O’Sullivan

Comment

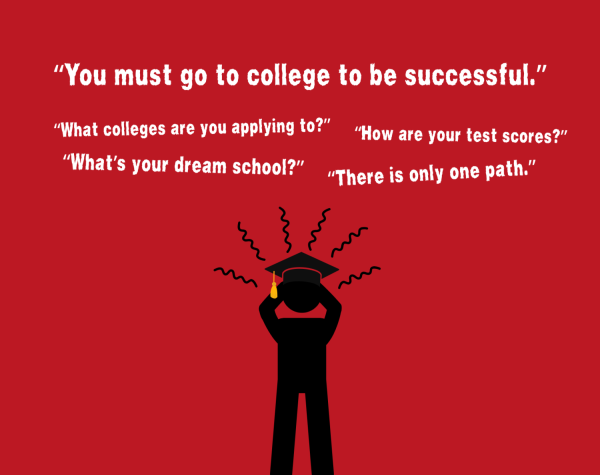

Over the years, the Grady cluster has advocated for separation of gifted, on-level, and remedial courses, a practice which increases racial, socioeconomic, and academic achievement gaps. While it levels out classes, so-called “tracks” hurt students in the long run, and should be replaced.

Students are separated early on. Many Grady students who went to elementary school at Morningside, Springdale Park and Mary Lin took participated in gifted testing before they could divide. I still remember “challenge days,” when batches of kids left class for the day to build toothpick contraptions and research narwhals.

A clear division was created when the on-level students, sometimes in classes of eight or fewer, spent the day reviewing old material. Teachers seemed fine with this; after all, it was easier for them to teach when they only had one skill level to work with.

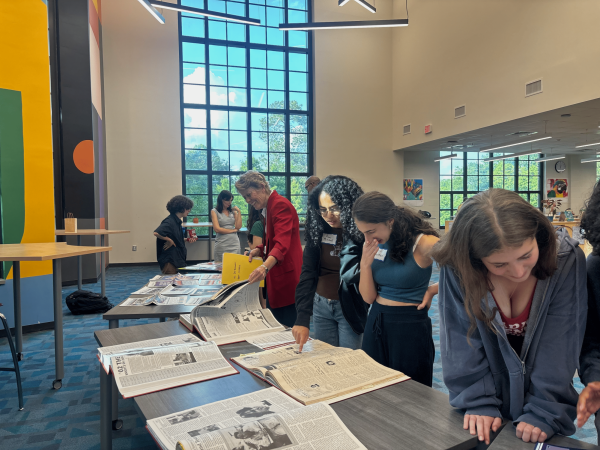

Challenge didn’t affect much in elementary school, but when it came to middle school courses, gifted designations created a stark divide between student populations. Students who were already in the gifted track were sent to higher level math and homogenized humanities, creating segregated classes that remained separate into high school.

Middle school math programs were based largely on gifted testing that wasn’t necessarily accurate or applicable to the content. One student was denied gifted placement multiple times because he couldn’t pass the creativity test, a standardized assessment which graded children’s drawings. APS policy prevents him from entering the accelerated track as a result.

While separative, a 2008 MetLife Survey of educators found that 43 percent of teachers agree to some extent that ability-based courses are easier to teach. Dividing by level certainly allows for more individualized learning and allows the class to move at the pace it needs to. Gifted students can go in depth on topics they care about, and students who are behind don’t have to struggle to keep up with lessons they don’t understand.

Unfortunately, educational researchers Douglas Harris and Carolyn Herrington found in a 2006 study that tracking causes a wider achievement gap between gifted and remedial classes.

I believe there is definite academic merit in moving at a comfortable pace, but only the gifted benefit from the system. Tracking is unfair to on-level students who work hard but have trouble keeping up. Its policies also prevents those who didn’t test into gifted early from changing classes. The repercussions can impact students both academically and socially.

“White and Black American children’s implicit intergroup bias,” a 2012 study by Yale’s Psychology Department, shows that white children develop biases by age seven, and only begin to question them and base their ideas in the environment around ten.

With the current system in the Grady cluster of feeder schools, classes are split into long-term tracks in sixth grade, hardly a year after students begin unlearning racial bias. Less exposure to peers of different races, socioeconomic statuses, and abilities may widen the gap between classes both socially and academically.

I agree that separating classes by academic ability is an easier way to teach, but the social toll is too great to begin division in elementary school. From as early as first grade, abilities determine who we meet, who we accept, and how we learn. If the district encouraged more integration of ability levels, the whole cluster would broaden its horizons. We can’t truly take pride in Grady’s diversity if our classrooms don’t reflect it.