Fate of local Confederate symbols remains uncertain

September 21, 2017

While Stone Mountain, with its carvings of Confederate generals, may be the most visible piece of Atlanta’s Confederate legacy, it is far from the only monument for the Civil War-era South in the metro Atlanta region.

However, some of those local memorials could soon meet the same fate as Old South symbols coming down in cities across the country such as New Orleans and Baltimore. In both cities, statues of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee were removed.

“I see both sides of the issue,” U.S. history teacher Lee Pope said. “As a history teacher, I think that if we don’t have things that remind us of the wrong in the past, then it goes away, and I feel like if you get rid of them, people are going to give a pass to the fact that the Civil War was here and that slavery was a thing. Maybe it is that we need to put some other kind of statue up, something that’s more a memory but apologetic.”

Locally, attention focused on memorials with the defacing of the Peace Monument in Piedmont Park. This statue, constructed in 1911, features an angel standing above a Confederate soldier, guiding him to lay down his weapon. Outraged and inspired by recent and similar efforts to remove a Robert E. Lee memorial that sparked violent protests in Charlottesville, VA., protesters gathered on Aug. 13 to tear apart the statue.

“I may not agree with the people who were from the Confederate Era who have statues,” Shawne Giustra, an Atlanta artist, said. “I may not agree with their thoughts or what was going on at that time, but I think to wipe the Confederacy off the face of the Earth is not a great idea because it is our history, and when we’re not aware of that history, there’s a chance that we can repeat that history.”

Other monuments around Atlanta under scrutiny include: The Lion of the Confederacy statue and the Confederate Obelisk in Oakland Cemetery, a bust of Sidney Lanier at Oglethorpe University, the statue of Henry W. Grady on Marietta Street in downtown and the General Walker Monument on Glenwood Avenue.

“The good thing is that all of this has raised awareness, and we aren’t those people anymore,” Giustra said. “We’ve come a very long way from that place. It doesn’t feel like a positive step, in my opinion. I think there are better ways to have dialogue about these issues instead of doing something that feels kind of violent and destructive.”

Confederate memorials were erected primarily after the Civil Rights Act in 1954, a century after the Civil War ended. They were enacted as a symbol of resistance to integration, public accommodations, and education. These memorials were not erected right after the Civil War because at the end of the Civil War, the movement toward secession was viewed as treasonous.

“I think that history is history,” said Calvin Vismale, executive director of Rainbow PUSH Coalition. “I think we should be sensitive to what is offensive, and I think we should be accurate about history. For example, we failed to have a number of monuments to many of the heroes of the Reconstruction Era right after the Civil War. I think it should be a balance, but it should be accurate.”

Many citizens have requested a name change of Confederate and East Confederate avenues, two streets that run through the communities of Grant Park and Ormewood Park. However, some people don’t find a name change necessary.

“I don’t really have an issue with the talk of changing the name of Confederate Avenue,” Pope said. “You don’t have to get rid of stuff; you need to acknowledge the things for what they are.”

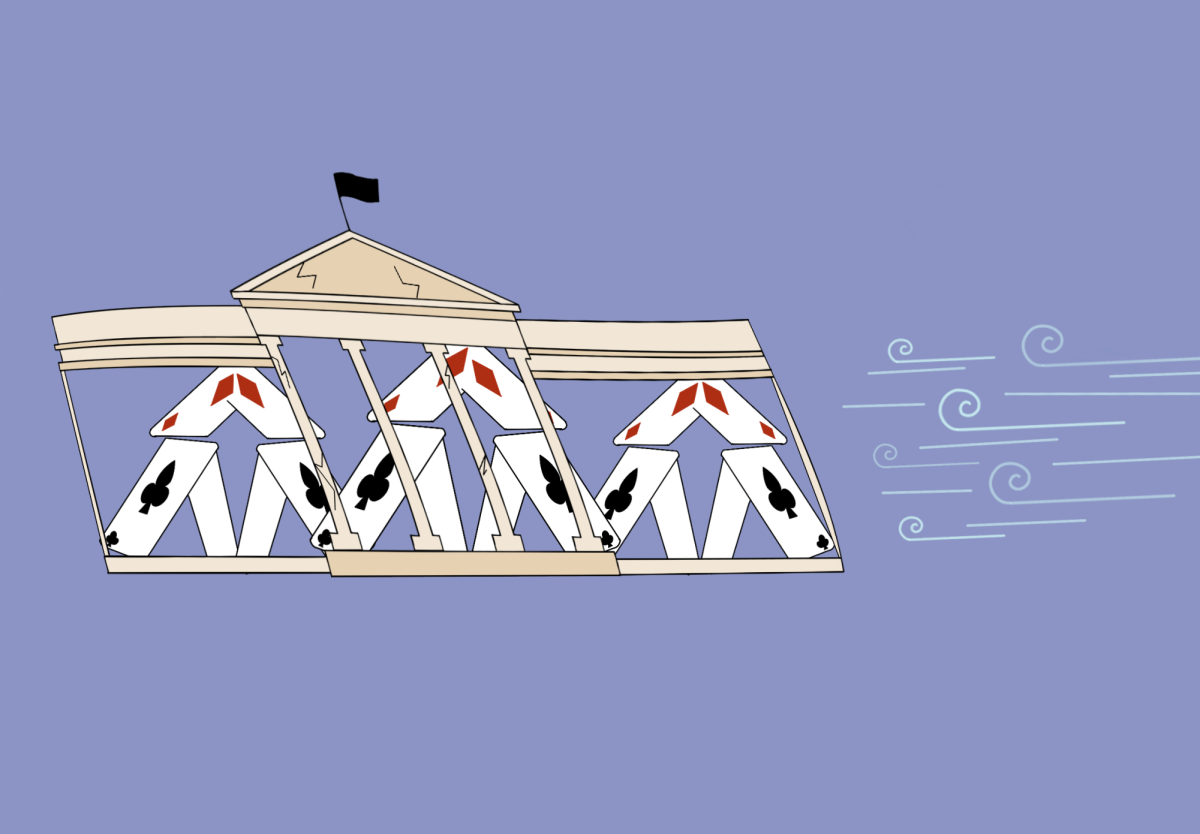

A main concern is that U.S. history, both the good and the bad, will be obliterated if the monuments are removed.

“We should focus on ways to come together as a nation and overcome the challenges that divide us,” Vismale said.

For related stories, see: https://thesoutherneronline.com/64724/news/treacherous-words-the-first-amendment-in-the-new-age-of-protests/

Annie Zintak