Solar eclipses create bond between Grady in 1984, 2017

The solar eclipses of 1984 and 2017 are remembered and treasured by Grady’s past and present.

Pictured is the solar eclipse of Aug. 21 in totality, taken during the two-plus minutes of 100% totality. Photo by Anderson Thrasher

August 22, 2017

By Olivia Podber, Co-Editor-in-Chief

The first tell-tale sign that a solar eclipse was occurring was the sheer magnitude of people who, in unison, pointed their glasses-covered eyes toward the Sun.

It was 1:06 p.m., exactly as NASA had predicted, on Aug. 21, and the first solar eclipse to cross the continental United States in almost a century was underway in the Southeast.

By 2:36 p.m., outside of Metro Atlanta, ranging from Northeast Georgia to South Carolina, spectators got, for many of them, their first and last glimpses of totality as they removed their ISO (International Standards Organization)-regulated glasses for two minutes and stared at the spot where the Sun used to be and the Moon then occupied.

“It’s really hard to describe what totality was like,” said Anderson Thrasher, senior at Grady and a nationally-recognized science fair participant specializing in astronomy.

Thrasher, describing totality as “totally awe-inspiring” with “no pictures really do[ing] it justice,” photographed the event through a camera attached to his telescope.

“I got a few glimpses through my telescope during totality and saw bright red prominences near the surface of the Sun,” Thrasher said. “If you looked around, you could see four planets all in a line from the Sun, which is a really unique perspective since normally you only see planets in the night sky, but here it was like you could see the whole solar system together.”

The first solar eclipse reportedly occurred 3,000 years ago, during a time when humans didn’t know that the Earth revolved around the Sun, let alone what a solar eclipse signified. There were innumerable theories, mostly ceremoniously based, trying to justify what it meant when the moon blocked the light of the Sun.

Ninety-nine years ago, with the progression of science introducing new technologies besides the naked eye, people were able to view the last spectated total solar eclipse with new equipment. In 1918, the eclipse was tracked as it moved from Japan to the Pacific to the entirety of the U.S.

In more recent times, on May 30, 1984, an annular solar eclipse crossed the southeast U.S., including Atlanta, for the last solar eclipse in the nation during the 20th century. An annular solar eclipse means the moon’s apparent diameter is smaller than the sun’s, blocking most of the sun’s light and causing a ring (or annulus) of light to appear. Nineteen-eighty-seven Grady alum Molly McHaney remembers the experience as one she’ll never forget.

“We made those pinhole cameras out of cardboard,” McHaney said. “And we went outside, and it was really weird. I remember it started to get really, really dark, and everyone started freaking out. The birds started to get very quiet, and you could see little showers of the moon crescents, filtered through the trees, all over the courtyard area, which was between the two gyms [at Grady]. There were these crescent moons all over the place, and I remember everyone saying, ‘Don’t look at the sun directly. It’ll burn your eyes out!’”

Lisa Willoughby, AP Language and Composition teacher at Grady for the past 30 years, was working as a student teacher at the school in 1984. On May 30, she had just graduated from Agnes Scott College and was heading to Grady when the annular eclipse occurred.

“It was 1984, so already the symbolism of 1984 and graduating, ending one part of my life and beginning another, created some significance,” Willoughby said. “I remember as I walked out [of Agnes Scott] and saw all those little [crescent] patterns on the ground that were created by the light shining through the trees, I thought, ‘this is really pretty cool!’ It was a special moment. By the time I got to Grady that day, it was over.”

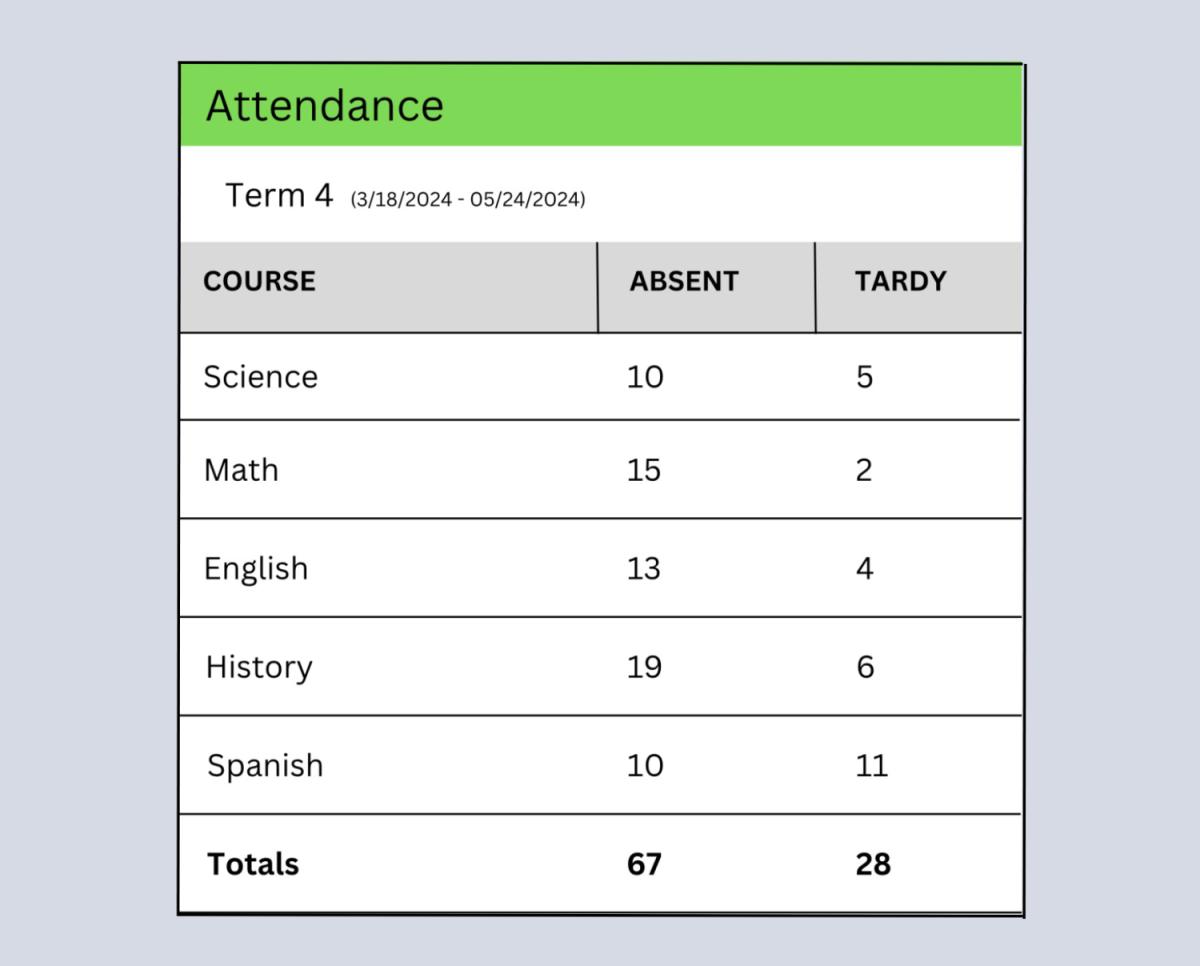

While Grady didn’t make provisions for the eclipse in 1984 besides, according to McHaney, “notices that went out that said, ‘Don’t look at the sun directly,’” the science department at the school did more to prepare for the once-in-a-lifetime event on Aug. 21, 2017.

“This is the first eclipse that’s crossed the entire country in almost 100 years,” said Ben Sellers, Grady astronomy teacher. Grady is the only school in the Atlanta Public Schools system to offer an astronomy class. “We collected some eclipse temperature data. I had several students doing that. And then we used two pairs of eclipse binoculars, and we used three wooden solar telescopes. We kind of just enjoyed it, other than that. I also filmed it with my Go-Pro.”

At 2 pm on Aug. 21, Grady students spilled out onto the football field and into the bleachers, glasses provided by APS in tow, to witness the state of 97.3 percent totality. Regardless of not having the full experience of totality, a dream for Sellers, he was still inspired by what he saw.

“It was grand,” said Sellers. “It’s an interesting time, in that we actually get to witness it. In the very near future, astronomically anyway, you won’t be able to see [another total solar eclipse in the Southeast], or if you do, it’ll be a repeat of one on video. I’m going to travel to Texas in 2024 to see one in totality. I’ve got the eclipse bug.”