Established in 2014 by Emory University, the Georgia Tech and Atlanta Metro Science Chamber, the Atlanta Science Festival takes place annually every March and produces a series of science-based events. Specifically, a blend of STEM and comedy arises through science improv shows.

Improviser John Mihalik has been doing regular improv for 12 years after participating in his first stand-up comedy class.

“I found [improv] was a completely different thing than stand up comedy,” Mihalik said. “It was a different challenge, and it got me out of my comfort zone, and I love doing things that get me out of my comfort zone.”

Improviser Daniel Clanton, who works closely with Mihalik in shows, started doing regular improv in 2018 after working in technical fields and behind the scenes in theater. Like Mihalik, after taking a one-day improv workshop, Daniel said he was hooked.

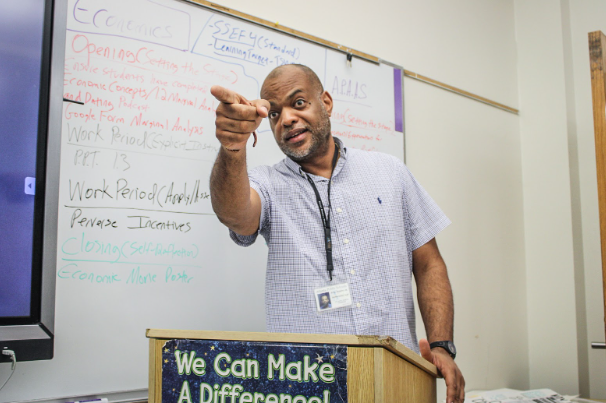

“I was always seeing people being on stage, being on camera, and … that’s something that I could do,” Clanton said. “I had a blast. I saw that there were some things that I felt I really needed to improve. When it came to my public speaking, when it came to the way I was thinking, I thought, ‘Yeah, I think I’m gonna sign up to see if I can help fix some of these things.’ And it really did. I really am thankful that I went in there and stuck with it.”

In 2021, Clanton was asked to perform in a science improv show. Science improv incorporates science vocabulary and references into the show. Although he never had a job in science-related fields, Clanton said he appreciated the new form of comedy and embraced this new challenge.

“I knew that [the science improv show] was a big deal … so I was honored to be asked to do that,” Clanton said. “That’s what I play into, is my lack of scientific knowledge. I have so much respect and admiration for scientists and the work that they do and how smart they are when it comes to that stuff. So, just to be amongst all of them … I’m just happy to be part of it because I contributed some type of way of making the Science Festival that much more fun.”

Improviser and host Alli Louie, who was previously a math professor at Emory University and is nowPython coder, started doing science improv in 2021, and as of last year, began to emcee (host) the shows more often.

“I think [emceeing and improvising] are very different because I feel like with emceeing, it requires more work ahead of time like [having to] write the show and making sure that everything is flowing well with the crew and everything,” Louie said.

With her background, Louie said emceeing shows caters better to her strengths, however she still enjoys improvising.

“I really enjoy emceeing because I’m a type A personality, so for me, it’s easier to emcee than it is to perform,” Louie said. “Also, with my math and coding background, I feel like I put more pressure on myself for improvising because I’m like, ‘Oh no, I actually have to deliver good science.’”

To plan for the shows, the improvisers get together to discuss the bits they may perform throughout the show.

“We, as a group, meet for a rehearsal at some point before the show, and then we discuss what kind of games we want to put in,” Louie said. “We look at previous years and see what we liked and what we didn’t like and then for the games that we like, we rehearse them together.”

Seasoned improviser Amanda Rountree has been doing improv for 33 years. Rountree said her favorite part about doing science improv specifically are the audiences and their captivation with the scientists.

“I mean, the audiences are so much fun because … it’s with the Atlanta Science Festival, so there is a lot of science,” Rountree said. “[There are] either actual scientists or just people who love science in the audience every year. It’s just fun to have a very specific audience. It’s kind of like open season on the science puns.”

While improv requires quick thinking, tough vocabulary terms make science improv more difficult, especially for those who may not necessarily be scientists.

“The key to improv is just commitment,” Clanton said. “So, if you’re going to be wrong, be wrong in an entertaining way. I’m just going to use that word in whatever type of way comes to mind. So, the science people either know it, and they’ll appreciate how wrong I am and then they’ll laugh at it, or they may not know what that word is, and they may think I know what I’m talking about, so either one of those outcomes is okay on the improv stage.”

To be out on stage requires a big deal of confidence, much of which Mihalik said stems from trust between partners on stage.

“What’s good about improv is knowing the people that you’re with up there on stage … have your back,” Mihalik said. “Whatever choice you make, they’re going to be right there with you.”

Rather than focusing on what the audience may be thinking, Rountree said the most important part of science improv is having fun.

“The advice I give to folks is that it’s really about having fun,” Rountree said. “A lot of times when we’re nervous to get up in front of people, that comes from us thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, what if I screw up? What are they going to say?’ But really, in the audience, people aren’t there looking to be the type of audience that’s going to judge you by throwing tomatoes at you. Audiences want to have a really good time, and they want to have fun, and so if they see that you are okay, and you are having fun, they’re going to be more at ease.”

![SCIENCE SCENE: Amanda Rountree [left] and Bret Bramkins [right] enact a slow-motion comedic act, using spontaneous vocabulary throughout the act. Rountree said she enjoys doing science improv because of the diverse audience.](https://thesoutherneronline.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/science-1200x900.jpg)