Attempting to reconnect the Flint River and surrounding communities, the Finding the Flint initiative tackles the mistreatment Georgia’s second-longest river has faced in conflict with growing development and the consequential impacts human actions have on those downstream. Now, the hope is to connect these once forgotten communities to the Flint River with an expansion of the BeltLine.

Hannan Palmer, previous Finding the Flint coordinator and author of “Flight Paths: A Search for Roots beneath the World’s Busiest Airport,” and Ryan Gravel, Atlanta BeltLine visionary, worked with organizations American Rivers, The Conservation Fund and Atlanta Regional Commission to launch Finding the Flint in 2017. Palmer said the mistreatment of the river is a reflection of her community in the path of development.

“As somebody who’s from Clayton County, I feel a lot of pride in my identity; this river becomes a symbol to me on how we treat people in the county and how we treat these communities,” Palmer said. “For too long, the county’s been treated like a dumping ground where you can just build a big airport there; nobody cares, well we do care. There’s a lot of culture and history there and communities that do care. Treating the river better and cleaning it up is a way of speaking up for the people who live alongside it.”

Spanning 344 miles, starting in metro Atlanta and flowing down to southwest Georgia, the Flint River plays a crucial role in Georgia’s water supply. The Flint River is composed of small creeks that flow together to form the river that continues to drift downstream. While once a defining boundary for the state, Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport and surrounding urban growth began to build on top of the river, increasing pollution and decreasing awareness. The Flint River was ranked on America’s Most Endangered Rivers List in 2013.

“Finding the Flint came out of a realization that there’s a need for restoration of the Flint River headwaters to benefit the river and the communities on the southside,” Ben Emanuel, American Rivers’s Southeast conservation director, said. “It’s a part of metro Atlanta on the southside where I think the benefits of natural assets for the local communities and planning to incorporate all that have been for many years been lagging behind other parts of metro Atlanta.”

A major reason for the initialization of Finding the Flint was the water wars between Georgia, Alabama and Florida in the dispute over the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF), lasting more than three decades.

“[The dispute] is a big deal,” Palmer said. “We all need water to survive … All of this is kind of out of sight, out of mind, but we still rely on freshwater and, particularly, in times of climate change when we have these long droughts, every household, farm and business is trying to secure their water supply. That’s a story for all of Georgia’s rivers, but the Flint is important because we have built this airport right on top of the headwaters, a lot of really intense development on this fragile ecosystem that the rest of the state relies on.”

As agriculture ranks as a leading industry in Georgia’s economy, Emanuel said the health of the Flint River downstream is vital to residents across the state.

“Further south, the Flint is critically important to the farm economy of southwest Georgia,” Emanuel said. “There’s a lot of area in the southwest area of the state that’s a really productive farm economy. The Flint River in that area is really closely tied to the groundwater and aquifer. So, farm water use from wells and underground is closely tied to water in the river and streams. … The Flint is really critically important as a water supply source for the farm economy and as a whole in southwest Georgia.”

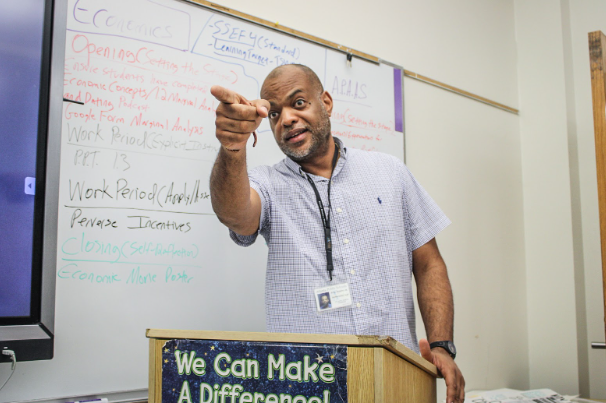

Latin teacher Scott Allen has known Emanuel since their freshman year at the University of Georgia, both having several classes together and living in the same dorm. Becoming good friends over the years, Emanuel’s sustainable river efforts rubbed off on Allen to incorporate these efforts in his own classroom and help students understand the importance of not taking for granted turning on the faucet. As simple as the action originally seems, Allen wanted students to realize the complicated process of how the water gets to our sinks and where it goes from there while also comparing how ancient Romans found their water sources.

“Certainly Finding the Flint has as an organization, and from what I understand, they just continue to grow, and it seems like a lot more people are interested in taking their tours,” Allen said. “It’s interesting because the Flint, for us here in Atlanta, it just starts off as this stream, but if you talk to people in south Georgia, it’s a really big deal. Finding the Flint and organizations like it are trying to stress that, ‘Look, what we do to the Flint here has major repercussions for people, our own fellow citizens that live downstream.’”

The Flint River is home to a variety of endangered species, from four species of federally endangered mussels to the Halloween Darter listed as vulnerable under the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species. Along with designated critical habitat declared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife service that stretches throughout the river, the health of the Flint River is key to maintaining this biodiversity.

“The Flint is a really fascinating river because it has an intact vibrant river ecosystem, and it’s sort of paradoxical that the river’s source is in the city and at the airport,” Emanuel said. “Part of the reason that the Flint supports vibrant river ecology is that there are very few dams on the main stone of the river. From the headwaters of metro Atlanta all the way down to near Cordele, Georgia, there are no dams on the mason of the river. That leaves a lot of the river system intact; there’s not a big reservoir in that area like there are in so many other rivers in Georgia, the south and in the nation. A lot of species depend on a natural river habitat, so that’s why some of them still persist.”

Remaining pieces of history linger around modern growth, such as Lee’s Mill, dating back prior to the Civil War. Palmer describes surrounding rivers as Atlanta’s lifeblood and the ancient waterways that have historically defined Georgia.

“All these creeks around Atlanta were the foundation of our settlements because that’s what people would go to get their drinking water, do their milling [or] do their baptizing,” Palmer said. “Before the railroads came in, these creeks would have been where you could jump in a canoe and get free transportation downstream. The earliest settlers of this area knew where the creeks were, where they led, where they could be damned and flooded. It’s funny how these creeks and the Flint River are completely hidden away as this was this nuisance, when for thousands of years, it was the free resource that meant people could survive and thrive in this area.”

Growing up in Clayton County, Palmer witnessed firsthand the impact industrial growth had on her community.

“My first home was in the city of Mountain View,” Palmer said. “Mountain View is a city that was completely bought out by the airport; everybody was moved out, and the city doesn’t exist anymore because of the airport’s encroachment … All the houses that I’ve ever lived in Clayton County are gone, more or less, because of the change of the area from residential to the airport and all the industrial uses around the airport.”

Palmer first noticed the Flint River while researching for her book that explored urban history while also diving into her personal experience of losing her neighborhood to surrounding development.

“I was trying to figure out what happened to my old houses,” Palmer said. “In the process, I learned that hundreds of other homes, businesses, churches, schools were relocated and demolished to make way for the growth of the airport. I felt that wasn’t a story I understood very well, even though I grew up in the area, and I felt it wasn’t a story that was being told about the airport’s impact on the southside.”

Finding the Flint works to change this historical mistreatment by connecting to those impacted in the surrounding community.

“It is sort of summed up in that tagline of reconnecting the Flint River headwaters to local communities in the airport area,” Emanuel said. “It’s partly about restoration of the river and streams themselves to benefit the river system and areas downstream, and it’s also very much about finding the river again in the landscape of local communities throughout the tri cities (East Point, College Park and Hapeville), Clayton County, the whole airport area. We’re about reconnecting the river to itself where we have a chance to do that, and also working the river system back into the fabric of the built environment and local communities.”

Attempting to rebuild these disconnected communities while spreading awareness on the environmental, economic and social impacts the Flint river has on those in metro Atlanta, as well as those downstream is a main goal for the initiative. Disrupting the narrative that the Flint River isn’t cared about is a cycle Palmer works to break.

“Finding the Flint, along with other organizations, are working to change [the pollution and degradation of Georgia’s rivers] to restore access, restore health and dignity to these waterways that are part of our communities,” Palmer said. “I think we know about the Chattahoochee, but these degraded rivers don’t get any attention, and it becomes a cycle where, ‘Well we can just pollute that river because nobody uses it.’ Well, no one can use it because it’s polluted. At some point we have to disrupt that process and narrative that’s a river that nobody cares about.”

Emanuel said starting the Finding the Flint initiative took collaboration across fields, engaging a variety of organizations in the conversation, including Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, to work towards a goal of green infrastructure.

“Green infrastructure, in general, is all about getting the landscape in a city to act more like the landscape in a forest from the perspective of how water moves through the city,” Emanuel said. “In general, in a developed area, when water hits pavement or rooftops, unless it’s well-managed, it tends to rush off quickly downstream, which is not the natural water cycle. The natural water cycle is more the water soaks in slowly into soil; it’s used by plants; it’s filtered by soils and it slowly makes its way into streams and rivers, recharging groundwater and stream flow slowly and naturally. The more that we’re managing water that way in a developed landscape, the more we can reduce flooding impacts in the city and in areas downstream.”

Last year, Finding the Flint and Atlanta Regional Commission applied for a federal grant from the Department of Transportation through their Reconnecting Communities program. The grant amounted to $65 million for a trail outlined to bridge more communities to the Flint River and an additional $25 million for flood mitigation work south of the Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, coming to a total of $90 million to develop and build multi-use trails along the river. Palmer said she hopes this grant serves as a tool to further connect the river with local communities.

“The idea is if you can bring people back to the banks of the river in a way that’s safe and beautiful, it raises awareness,” Palmer said. “It changes the kind of development in the area if we have these recreational amenities. Currently, if you want to go recreate on the Flint River, you have to go way far outside of Atlanta to get to the river. So, we’re trying to change that. We created a plan called the Flint River Gateway Trails and basically when we build out these trails you’ll be able to get from the Atlanta BeltLine on the west side down to the headwaters of the river and then bike along the river all the way around the airport and into Clayton County.”

While Palmer has heard from those in Atlanta that residents are excited to expand walking and biking trails alongside a beautiful creek, residents in south Atlanta are also looking forward to the flood mitigation that comes with the grant.

“South of the airport, the Flint floods really badly,” Palmer said. “That has to do with development around the airport and impervious surfaces. It also has to do with climate change and more intense storms. People have major flooding in their homes, because they’re close to the Flint and its tributary. Getting this grant is a relief to them that they might start to see some detention and green infrastructure projects that will help mitigate the flooding in their neighborhood.”

With the approved grant, Palmer said Finding the Flint is already beginning to notice that elected officials get excited about what is possible for the river and a shift in awareness from the community after years of Finding the Flint’s dedication. With that shift in thinking differently, Palmer said the grant feels like an endorsement of the initiation’s idea to reconsider these hidden margins of the city and think of them as assets.

“I feel like when we first started, I didn’t know much about the Flint, and I feel most people I talked to didn’t know much about it at all,” Palmer said. “Certainly, the mayors and the city council of the Tri-Cities did not know anything about the Flint. I even had a conversation early on with a public works person who referred to it as ‘an alleged river.’ As we talked about this as a river, I was viewed with a lot of skepticism … Historically, if you look pre-airport, it’s on the map, the Flint River. We just decided it wasn’t a river anymore when we wanted to build on top of it. Just the awareness of the river, the respect and knowledge of this whole connected ecosystem, that’s completely changed.”

To engage his students in keeping Georgia’s rivers clean, Allen inspired action when he took students to Atlanta’s R.M. Clayton Water Reclamation Plant earlier this year. Allen and his students also took samples from four water fountains at Midtown to send to UGA to test the safety of our drinking water. In a continuous effort, Allen earned his certification with AP Environmental Science teacher Beth Kostka to take water samples at Clear Creek, the tributary of the Chattahoochee that runs under Midtown.

“I think we just take for granted every time we turn on the faucet,” Allen said. “Like, ‘Oh, of course the water’s going to come on.’ Where does it come from? It’s important to know we are treating the wastewater effectively before we can move back out into the river, which then people downstream will take to use for drinking water. It’s all about cyclability.”

While it may seem daunting at moments, Palmer said Finding the Flint’s goal to connect communities to the mistreated river has been an anchor in persevering with this initiative. Emanuel and Palmer said the Flint River is only the beginning of what they hope the community will take away from the initiative, continuing to protect Georgia’s natural ecosystems throughout the state.

“Once you start looking at one urban river, you realize that these conditions are similar in lots of other urban creeks and rivers,” Palmer said. “I’m devoted to the Flint because I grew up in Clayton County, and it’s this huge opportunity to connect communities that were disconnected by the airport’s growth, but really wherever you are in Atlanta or in Georgia, you have a creek. You’re in a watershed; you’re part of a connected network of waterways, and I just find it a really interesting and valuable way of looking at the world.”