Baby boomers remember sitting on the couch, eyes trained on the TV, watching Walter Cronkite deliver the news of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination. America cried, and he cried with them. Others recall listening after dinner to trusted news anchors relay the rising body count of the Vietnam War. For the first time, evening news brought home videos of combat that painted a different reality than what the White House presented. Americans trusted what they heard and saw because journalists put their names, faces, and reputations behind what they reported. Now, anonymous users calling themselves media can share virtually anything with the world, whether true or not.

Since the early 2000s, media consumption has shifted from print, television, and radio to online news outlets. Gone are the days when Americans would wake up with Jane Pauley and wind down with Dan Rather. America’s news diet has changed with the invention of social media.

According to the Pew Research Center, 54 percent of U.S. adults get news from social media. In a 2020 research study, Statista found that 38 percent of people admitted they have passed along news they knew to be fake via social media. Because of the increased spread of information through the internet, high schools need classes that help students recognize media bias and political propaganda to prevent misinformation and ensure understanding.

In a semester-long, required course students, would learn how to navigate social media by challenging themselves to ask where the content they consume is coming from. Is it connected to a legitimate news platform, or is it an influencer projecting an opinion that puts extra money in their pockets?

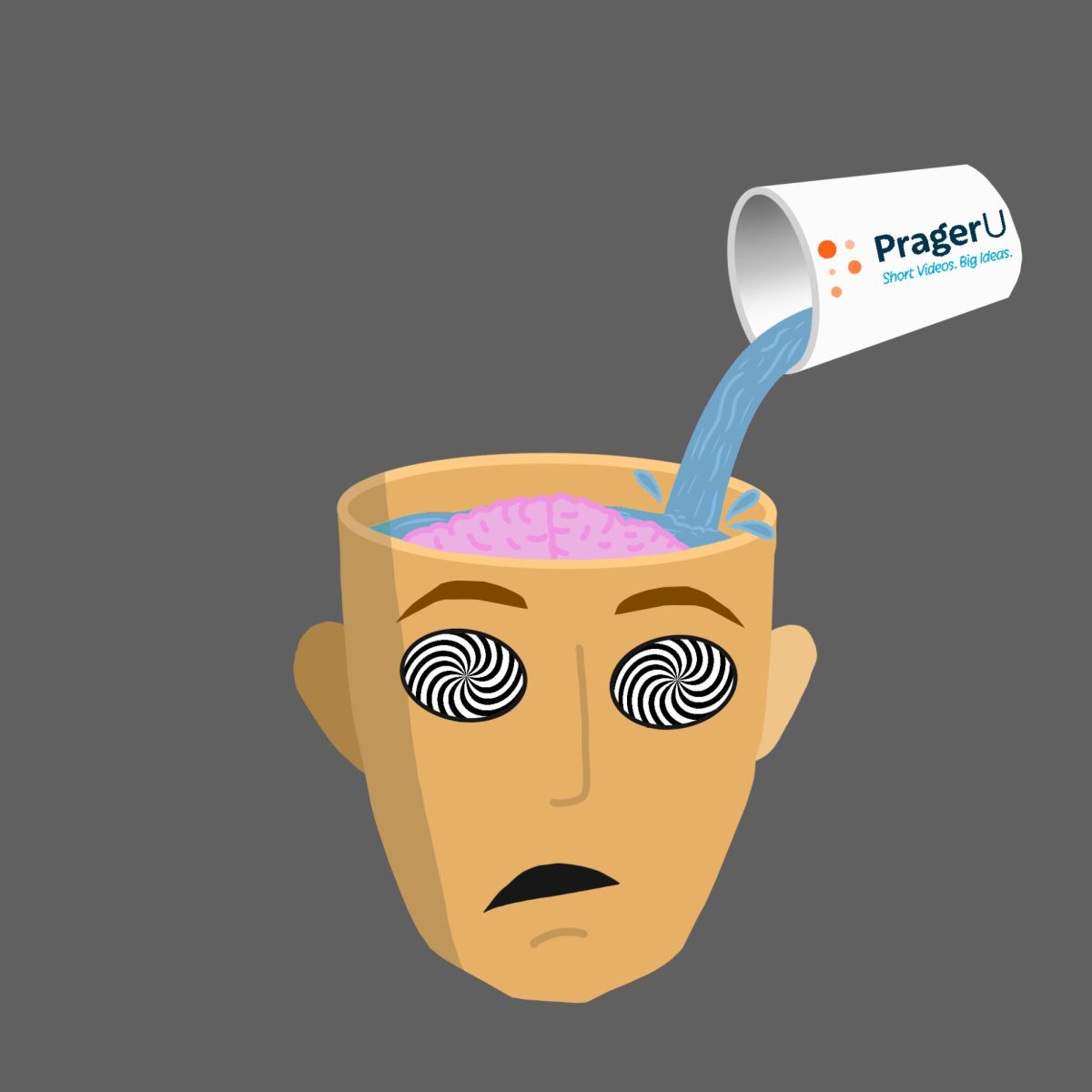

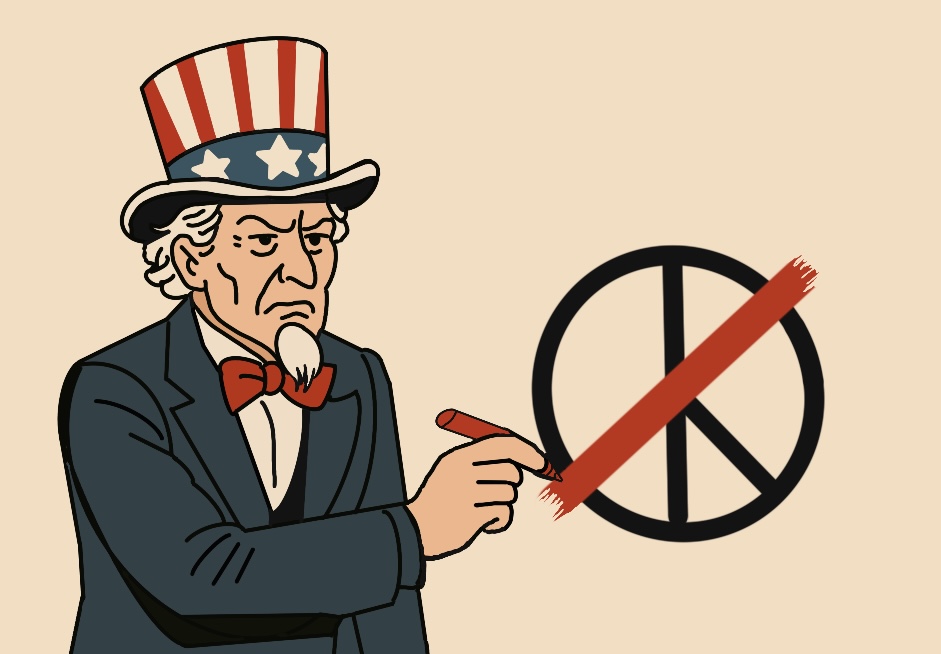

Often, viewers and readers are exposed to political propaganda that aligns with their belief system. According to Nature, people with strong partisan political identities found it hard to recognize media manipulation. For years, Russia, China and Iran have operated bot farms designed to send disinformation to American audiences that create national division. Being unable to tell the truth from fiction cannot sustain a democracy.

Even vetted news outlets can have writer bias. Journalists write stories from their perspective. Nuances change, but the facts remain the same. That’s why it’s important to get news from multiple sources. Sample different news outlets, you don’t have to commit to just one. Common Sense Media, a nonprofit, has a checklist that helps students identify false information. It flags TikTok and Instagram as unreliable sources. It teaches strategies for identifying clickbait and biased opinions and recommends using Snopes or FactCheck.org to verify information.

Arguably, delineating fact from fiction is a more important life skill to students than fulfilling a math or an English requirement. Not understanding if something is true or false can be dangerous and can erode faith in national institutions.

When Hurricanes Helene and Milton made landfall, FEMA, a federal disaster agency, had to dedicate a webpage to dispelling myths and false information. The situation got so bad that relief efforts had to be suspended because workers’ lives were being threatened.

Before social media, disasters fostered a sense of national unity. After the Twin Towers collapsed on 9/11, roughly 80 million viewers sat down together and watched the evening news. I’m not sure that would happen today.