The Georgia Promise Scholarship program will open on March 1, offering $6,500 in education savings accounts to students who live in areas served by Georgia’s “lower performing schools,” according to the Governor’s Office of Student Achievement.

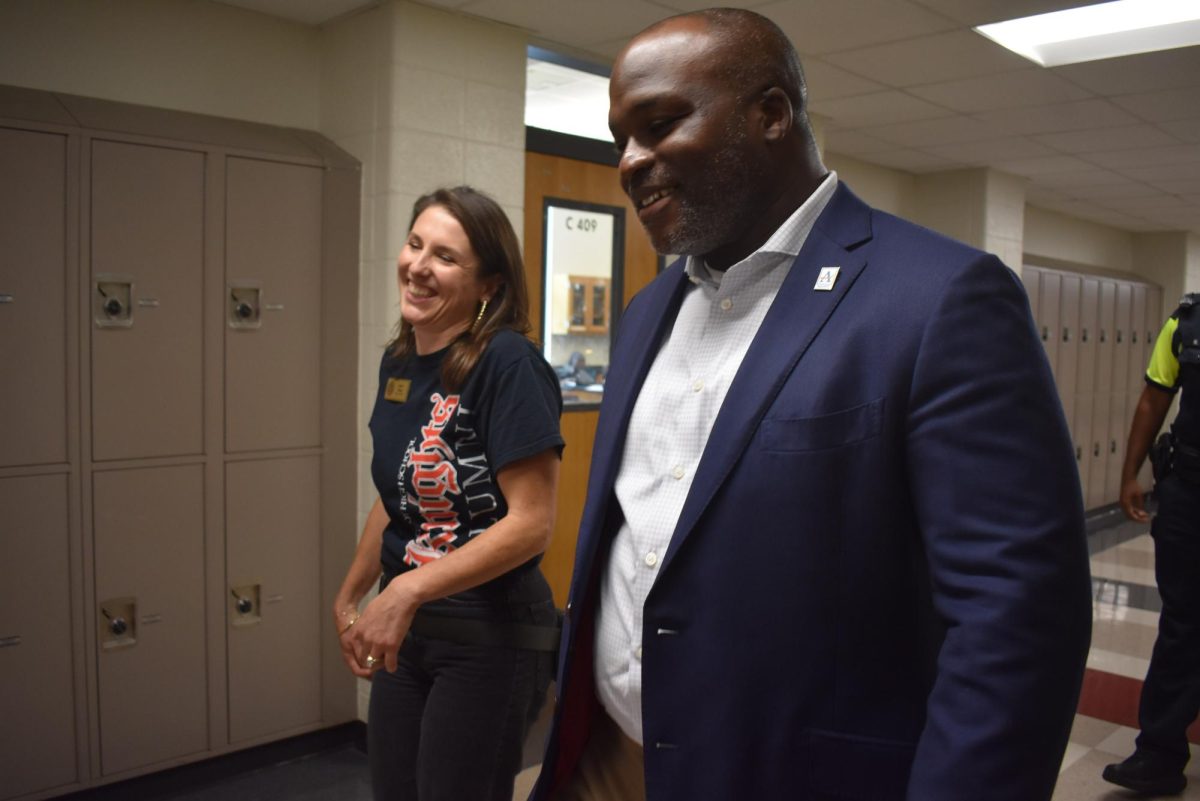

After over a year of deliberation, Gov. Brian Kemp signed State Bill 233 into law on April 23, 2024, implementing the program for the 2025-26 school year. The quality basic education formula funds public Georgia schools; part of the fund allocates money to districts based on the number of full-time equivalent students enrolled in the district. Every student who leaves a low-performing public school for a private school draws a set amount of money away from the district.

“I have issues with voucher programs, mainly because they take necessary funds from public schools and divert government money to private institutions,” Midtown English teacher Erin Aube said. “What I think you’re going to see is money taken away from struggling schools, the schools who need the money the most, so those schools will have no opportunity to improve.”

The program is limited to 1% of the $14.1 billion spent on Georgia’s K-12 school funding formula. This allocates $141 million to the program, enough for 21,000 to 22,000 $6,500 scholarships. Despite her concerns, Aube believes that this amount of money will not allow a mass transition by qualifying students.

“Six thousand, five hundred dollars is not nearly enough to cover private school at most schools,” Aube said. “Individually, you might see a handful of students be able to benefit from it, the ones whose parents can come up with the additional funds. But overall, I just don’t think you’re going to see a big impact.”

Students must currently be in a low-performing Georgia public school for at least two consecutive semesters or eligible to enter kindergarten in the 2025-26 school year.

Carla Key, parent and founder of Primavera School, agrees with Aube that the voucher program will not supplement the cost for qualifying students to attend private school.

“As a director, it would be wonderful to have the capability to enroll more low-income families using state funding,” Key said. “But from my knowledge as a private preschool director, the amount of money that is being offered in the private school voucher does not offset enough of the cost of a private school for low-income families to make it a feasible option. It would be enough for middle-class families, but usually middle-class areas are not low-performing.”

The scholarship may be used for “private school tuition and fees, required textbooks, tutoring services, curriculum, physician/therapist services, transportation services and other approved expenses.” Key believes, even if the voucher program covered the full cost of private school, there are intrinsic costs associated with voucher students at private schools.

“Travelling from outside neighborhoods and lacking the network system in place, it is difficult for voucher students to establish personal connections with private school families,’ leaving school voucher students isolated from both the private school community and their neighborhood community,” Key said. “In order for a voucher system to be successful, there must be intentional processes to integrate not only the student into the private school community but also the family.”

One of the additional approved expenses, according to the Georgia Education Savings Authority, which voted to approve the program in November, is transitioning students from low-performing public schools into homeschooling programs. Aube believes families may attempt to move their kids into homeschool without realizing the full responsibility it entails.

“A concern I had was I saw that the money could be used for homeschooling,” Aube said. “So, I think people who realize that they’re not going to be able to afford a private education for their children may take it upon themselves to homeschool them, which, if they’re prepared to take on the responsibilities and the burdens … I could see that as an issue, as well.”

As a teacher, Key has experience with the way children learn. She believes transitioning between schools sets children back in their learning process.

“Transience is a major problem in low-income schools,” Key said. “With each move from one school to another, a child has a three to six month academic regression. The private school vouchers, being transitory in nature, could hinder a child’s academic progress.”

It is not mandatory for private schools to participate in the program. As of Dec. 30, over 240 private schools had opted into the Georgia Promise Scholarship program. Key worked as a second-grade teacher in Clayton County for nine years. She saw firsthand the benefits of charter schools, and she believes a charter school would more effectively promote educational opportunities than vouchers to private schools.

“From my experience, the money would be more effectively used to fund a charter school that offers academic excellence and strengthens the school community,” Key said. “In the low-income school where I worked, we used extra funding to lower class sizes, bought the latest educational technology, funded a social emotional curriculum and received inspiring learning material grants. Charter schools are allowed to waive certain educational state rules and regulations and can implement unique academic and organizational innovations in exchange for increased accountability for student achievement.”

Families can apply for the program on the MyGeorgiaPromise.org website from March 1 to April 15. Students already receiving the Georgia Special Needs Scholarship or Georgia Student Scholarship Organization Scholarship can not apply.

Calhoun High School junior Chloe Edens attended Calhoun Middle School. While she would have been eligible for the program, her family would not have opted in.

“[I wouldn’t have used the scholarship program] because my family was pleased with the Calhoun city schools system,” Edens said. “And if we weren’t, there wouldn’t have been a private school to move to. But we had a very good experience with Calhoun. [The program] wouldn’t really affect us because the school system had everything we needed and helped us.”

Midtown students are not eligible to apply for Promise Scholarships because it is considered a high-performing public school.

“I’m lucky enough to teach here,” Aube said. “That’s the only reason Zelda, my daughter, gets to go here. We are fortunate and lucky, and all the students, we are fortunate, lucky to be able to go to a high-performing public school. But low-performing public schools are never going to achieve that status if the government just takes funds away from them.”

Junior Alexa Posel went to The Galloway School, a private school in Atlanta. She moved to Midtown freshman year. She believes Midtown offers more opportunities for her when compared to The Galloway School.

“Private school was obviously a lot smaller, with more chances to have personal connections with your teacher,” Posel said. “But Midtown has so many more people. I don’t only enjoy going to Midtown more; I have so many more opportunities. Midtown offers lots of clubs, sports and challenging classes, which I wouldn’t have been able to access at Galloway.”

Aube believes the program looks good on paper but will not have many long-term benefits.

“To me, this looks more like an optics issue,” Aube said. “It’s something that people see as a panacea that’s going to fix the education problems that we have. But at the end of the day, it’s not enough money to send your child to a private school. And the private school has no obligation to assume the public school child. They have admission criteria … I think, maybe it looks great on paper to some people, but in actuality, it’s not really going to help.”