Students, teachers grapple with education reform policy

Since the November election, there has been a growing conversation about federal education reform, leading students and educators to raise questions about their personal future.

“There’s a lot of anxiety among students right now,” senior Madisyn Walker said. “There are a lot of topics circulating, and you don’t know what is true and will happen or what is just lies. I’m always reading the news about politics and just trying to understand anything I can.”

Walker serves as one of 23 students on the Atlanta Public Schools Student Advisory Council, where she aims to bring issues she hears from her classmates to the district’s attention. She has heard a lot of concern for future education reform from fellow students.

“In my Women’s Studies class, we talked about [education] for half the class,” Walker said. “I know some people are really nervous about financial aid as they go into college.”

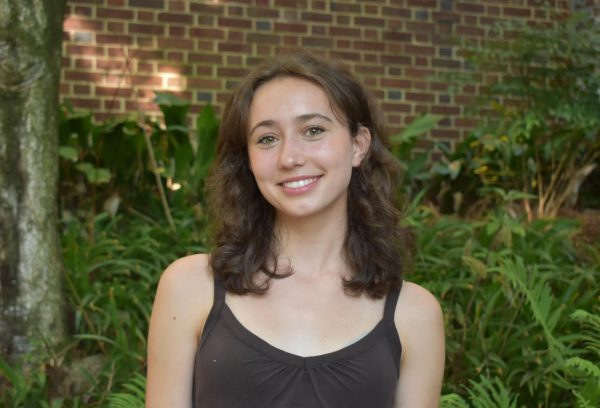

Senior Eden Sharp said she is looking at alternative options for her post-secondary education because of uncertainty around the political climate.

“I think moving to a blue state or overseas will make me feel more secure,” Sharp said. “I am currently applying to schools in the UK.”

The potential effects of the new educational policies have brought concern to the APS system. Katie Ludlam, president of Midtown’s Parent Teacher Student Organization and parent of three students in the Midtown cluster, believes the new policies could cut many vital programs in APS.

“I think most funding does take place at the state level, but the federal government provides some wonderful funding for Title 1 schools, special education initiatives and other important things that students need,” Ludlam said. “A lot of the concern is that if we lose the federal money, how does the state make that up? There’s a lot of repercussions that are going to be really hard on a public school system like APS.”

In the past year, politicians, including president-elect Donald Trump have led a discussion on the removal of the Department of Education.

On Nov. 27, U.S. Senator Mike Rounds (R-SD) introduced “Returning Education to Our States,” which would redistribute all funding for the DOE, $200 billion, to other federal agencies.

“The idea to abolish an entire federal agency that oversees compliance from multiple states is rarely a good idea,” social studies teacher Sean Jackson said. “We, as teachers, don’t really know what to expect but the trajectory of who [Trump] is choosing to put at the top of the Department of Education is very concerning already.”

District 1 school board member Katie Howard said a potential shutdown of the DOE would likely impact APS less severely than other school districts due to Atlanta’s strong property tax base.

“Seventy percent of our funding for APS comes from our property taxes in the city of Atlanta, so we are more fortunate than other school systems in Georgia,” Howard said. “It will be interesting to see if people actually talk about really doing away with the Department of Education, what legislators have to say who have counties that don’t have the same property tax base and financial support; they’re really reliant on those [federal] funds, especially for special education.”

Walker agrees a reduction in federal funding will reduce education equity and access for lower-performing schools.

“The idea of removing the Department of Education is very concerning because I really believe it’s going to target low-income communities that look like me,” said Walker, who is African American. “We already don’t give enough attention to low-income students, and this would take away any.”

Due to the DOE’s large role in Title I funding, federal support to schools in economically disadvantaged districts, Howard believes low-income areas of Georgia could face detrimental consequences if it were to be dismantled.

“There are schools that struggle to keep the lights on, struggle to keep books,” Howard said. “Georgia has some really low-income areas; so, they’re very reliant on those Title I dollars. So that would be devastating for them. I don’t know exactly how they’re using that money, but maybe technology [and] books are making up a big part of their budget.”

Student support person in the social studies department Claudia Black emphasized that programs for students with disabilities have been historically marginalized and are protected by the federal DOE.

“Education takes a lot of money, and often, schools will not do what is in the best interest of students unless there is a government agency requiring them to do so,” Black said. “If there is no Department of Education, the Free and Appropriate Public Education mandate will go away, which ensures a quality education for all students with disabilities.”

Black serves as one of nine Midtown support staffers for students with learning disabilities and said she is concerned for her job under the Trump presidency.

“I am having to look for new jobs,” Black said. “Right now, there are two extremes in opinion: people that think there will be issues and people that believe nothing is going to happen. I do not think anything is happening overnight, but my entire job is interventions for people, which falls under the Department of Education, which is under threat right now.”

However, AP Biology and Environmental Science teacher Nikolai Curtis believes that abolishing the Department of Education may be more difficult than many think.

“In order to get rid of the DOE, there has to be an act of Congress,” Curtis said. “When Ronald Reagan was president, he attempted to end the DOE, but Congress wasn’t interested in that at all. To do the same thing today, Congress is going to have to pass an act and agree on it.”

Howard said a potential DOE shutdown could have an outsized impact on special needs education.

“For many districts that don’t have as strong of a property tax base, probably the bulk of their special education funding would be impacted,” Howard said. “So, that can be [not having] enough educators. I think we all know that special education is an area where there’s a lot of high need. You want to make sure you have the right qualified and supported people in those positions working with kids with a cross section of needs. So, it’s not a deep pool. You need to pay them well, too. If they lose that funding, I think that would be a crisis for many school systems.”

Howard believes that while less funded school districts would face the largest impact from a reduction in funding for special education, most districts would still face challenges due to a lack of federal administration for special education programs if the DOE were to shut down.

“It’s an important part of oversight and accountability for school systems throughout the nation that somebody is there to ensure that students are having their needs met and there’s no violation of their rights, especially for such special education students, which that can obviously be a different landscape based on a students’ needs, and sometimes, there’s not that deeper understanding by people in individual schools,” Howard said. “In APS, we have the benefit of more resources, and we even struggle to make sure everybody understands how to administer that and support it.”

Social studies teacher Kelly Wren expects a reduction in federal funding for students with disabilities could indirectly impact state-funded gifted programs.

“Gifted programs are state-regulated and state-funded,” Wren said. “They are different from state to state. Some states have gifted programs, some don’t. Identification criteria, services and funding are all different state to state. That said, if states receive less federal funding for other programs and services like special education, which is federally regulated and funded, then it may indirectly impact how much state funding goes to gifted.”

Wren also said state-funded gifted programs could indicate how state-funded disability programs may function.

“Funding in Georgia is based on a count of the number of gifted students in a school and the amount of services they receive — how many segments they are coded to get gifted services per day,” Wren said. “In Georgia this year, the gifted program weight is 1.7340 x each gifted student service segment (where a general education high school student segment would earn 1.0 x base rate per segment).”

The DOE is currently the largest provider of financial aid in the nation, helping more than 9.7 million students afford post secondary education every year. With the removal of the DOE, funding and support for financial aid programs could be pulled, thus affecting millions of students across the nation.

Curtis believes that if the DOE was abolished, many students would lose access to financial aid, affecting diversity and inclusion at the college level.

“A lot of people don’t understand that the DOE disperses federal dollars out to states; they deal with student loans; they deal with maintaining equity, and they deal with following the law,” Curtis said. “If you get rid of that agency, there is no function to oversee if money is being misused.”

During his first presidency, Trump proposed significant cuts to Pell Grants, which provide financial aid for low-income students. Howard said this had a notable effect on the number of low-income students planning to attend college, and she expressed concern about consequences to the possibility of further cuts to financial aid.

“We saw so many kids who chose not to go to college because they don’t know if they can afford it or not, and they were more black students, more disadvantaged students, more first generation [students],” Howard said. “If we were to rip more funding away, the impact is going to be huge. We already know that colleges, universities have become more expensive with the changes around affirmative action that absolutely affect who is able to get in and then to take away another piece that’s really been critical, would be devastating.”

For several years, there has been a growing effort by Republican leaders to establish new restrictions on content taught, specifically surrounding critical race theory and literature book content.

Jackson teaches government and civics. He said he is worried about the potential modification that may occur to his curriculum.

“There are certain regions in the country that have an idea about what they want in education,” Jackson said. “[A reduction or removal of the DOE] would give states more control over everything as it relates to different protocols and processes for education. And if you’re in a certain state, i.e. the South, you may see drastic changes that come down the pipeline from a state decision.”

Jackson is specifically concerned about the removal of the conversation of racial equality in several classes.

“I discuss a lot about civil rights and civil liberties in my government class and U.S., world affairs, specifically,” Jackson said. “As a social studies teacher, if there is some kind of mandate that says you cannot talk about those things anymore, that puts me in a morally bad position.”

Media paraprofessional Christen McClain, who works in the library, believes a book ban would put pressure on teachers and be counterproductive to education at Midtown.

“A book ban would make teachers and staff more tense, and they would probably have to think twice about what they assign and what work they give,” McClain said. “Censorship and book bans would be stifling. Even if you don’t agree with something, it’s good to understand both sides of the issue. You can’t just pretend these issues don’t exist.”

Curtis thinks litigation would play a factor in the effectiveness of Republican officials’ plans for the censorship of content.

“There’s a series of checks and balances in the government,” Curtis said. “I’m intrigued to see what’s going to happen on the state level because laws still exist. The Establishment Clause that separates church and state may affect the initiative to put religion into the curriculum. The Constitution says you can’t do that.”

Ludlam believes that if the policy does come into effect, the consequences for education in Georgia could be dire.

“A federal cut of the DOE just trickles down to the state having to readjust their budget of how to give money to schools,” Ludlam said. “I think most schools are using every dime they are getting; so, I’m worried about the state of Georgia’s education.”