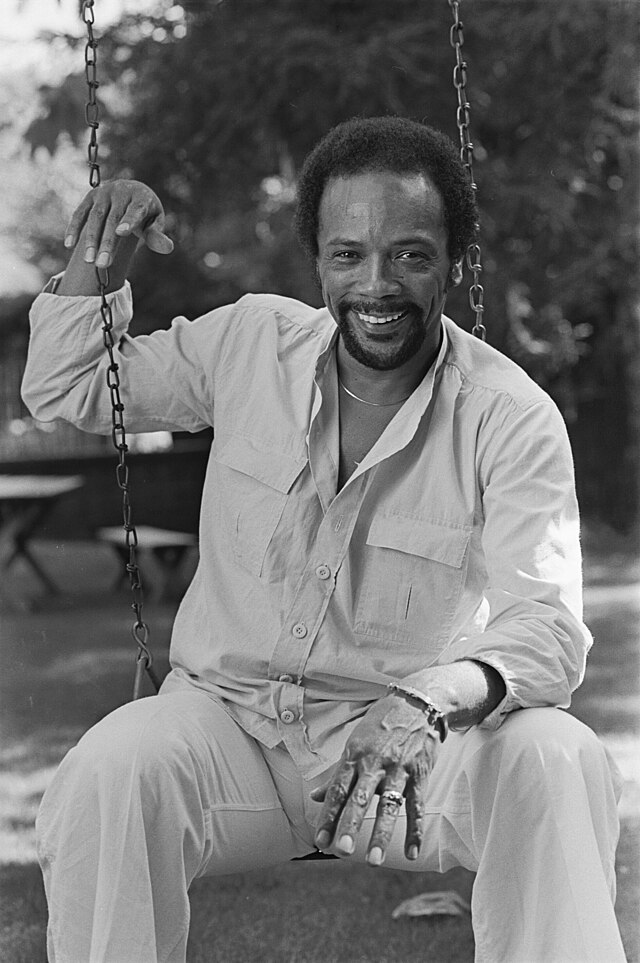

Quincy Jones, renowned producer, composer, leaves legacy of influence and innovation

Quincy Jones, a prominent figure in both music and social activism, died on Nov. 3, 2024 at 91-years-old. Jones left an unparalleled legacy over his seven-decade career as a record producer, composer, arranger and trumpeter.

Jones received 28 Grammy Awards, along with multiple nominations for Academy Awards and Golden Globes. Jones worked with renowned artists, including Frank Sinatra, serving as the arranger and conductor of “Sinatra at the Sands,” and produced Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” the best-selling album of all time.

“He knew music in every aspect – you could talk to him about Baroque music, strict counterpoint,” Giorgi Mikadze, producer, pianist and Berklee College of Music associate professor, said. “He was trained really well. He was one of the most influential arrangers, as a jazz arranger and big band arranger. [He arranged] for Miles Davis, Frank Sinatra, I mean the list of names is so long.”

Mikadze, who knew Jones on a personal level, admired his charisma and humility as a person.

“It’s easy to see how he is so respected,” Mikadze said. “People did love him, they genuinely loved him. First of all, on a personal level, [he was] a humble man, and was such a grand person. You feel like he’s with you, and he supports you. And it doesn’t matter which phase of your life you are in, the impact is that he influences you to be a hard worker, be nice, be humble, and your talent is going to speak out in the end.”

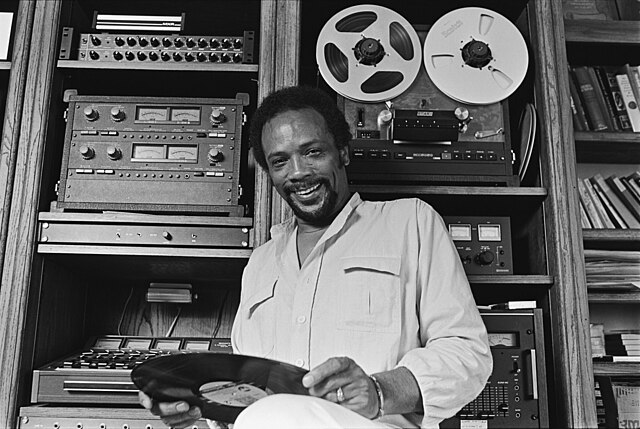

Jones was well known for his unique ability to blend musical styles within the American music industry and his adaptability to the changing technology supporting music production.

Midtown band director Carlton Williams said Jones’ career rose at a time when big band jazz began to dominate the music industry.

“He was born and raised in Chicago, like in the early 30s,” Williams said. “That’s when a lot of the big band era really started to evolve … It made a profound impact on the people that were doing jazz arrangements back then before any big films. But I think that arrangers and composers all benefited from his style.”

Mikadze said Jones’ skill of transforming artists’ visions into music was evident in his albums and the impact he garnered as a producer.

“He could translate,” Mikadze said. “When he was a producer and working, for example, for Michael Jackson, Michael Jackson had his own vision on his songs, and he was able to literally sing every part, like guitar part, bass part, out loud. And [Jones] had to really catch it and play it on his instruments. So as a live arranger, [he] had to understand at a different level what the artists wanted, and he had an amazing sense of understanding of what the other artists wanted to create and translated it into musical instruments.”

James Weinman, a jazz pianist and professor of African American studies at the University of Georgia, said Jones’ influence extended beyond jazz, shaping the careers of many artists.

“I think his music disseminated all over the place,” Weinman said. “You think of the collaborations of Michael Jackson, I don’t think those albums would have been what they were if it wasn’t for Quincy.”

Weinman said Jones’ music flourished through film as well as radio music, producing film scores for Will Smith’s “Fresh Prince of Bel-Air” among others.

“He was high up there; he was able to be a mover and a shaker, even with the jazz people,” Weinman said. “He never forgot his jazz roots … I think that part of him being able to be in the space that he was and being able to do it well, and you could tell, as at a young age, that he was smart, and he was inquisitive, and everything he did, he did on a high level.”

Jones’ enduring legacy extends beyond his musical achievements to the personal connections he fostered and his ability to inspire others.

Mikadze grew up in Georgia studying classical music but was particularly drawn to Michael Jackson as a child. After learning Jones had produced much of Jackson’s work, he began to learn about him and admire his accomplishments.

“I got accepted at Berklee College of Music under full scholarship, and I was so happy,” Mikadze said. “The first thing that I saw was his picture in a Berklee library as he was a student at Berklee, so I was really excited. I had seen this show on YouTube from the Montreal Jazz Festival, and all these all-star musicians together, playing and celebrating 75 years anniversary of Quincy’s life. It was such a memorable concert, and I was thinking, ‘Why don’t I do something for him?’”

Mikadze’s admiration for Jones inspired him to organize a tribute concert in 2013 at Berklee to honor Jones’ 80th birthday. While Jones could not attend, Mikadze said the event, which featured artists Jones had produced, was a memorable success.

“We had two of his produced artists such as Siedah Garrett, one of the back vocals of Michael Jackson, and Patti Austin, a jazz singer, so meeting them and hearing their stories with Quincy was incredible,” Mikadze said. “The [Berklee] vice president did announce that it was all my idea to make this Quincy Jones tribute show, and Berklee absorbed it and they supported it.”

Six years later, Mikadze met Jones for the first time and said his interaction with Jones left a lasting impression on him.

“I decided to tell him the whole story of how he became my idol, and the most important thing that I felt from the beginning of when I was talking to him, I felt like I was talking to my friend,” Mikadze said. “I was talking to a person that was willing to share anything. There was no barrier between us, he was so friendly, so supportive, and he was listening to me.”

During their meeting, Jones gave Mikadze a bracelet as a gift, something he said he cherishes to this day.

“He put me on his equal as a musician, and I felt great,” Mikadze said. “He gave me his bracelet. It’s a peace cuff that has all the religions, and the idea is that music has so much power. This is the bracelet that I wear, often publicly, especially at concerts.”

Williams said Jones had a unique ability to bring people together, fostering partnerships that amplified the talents of everyone involved.

“Even today, people are referencing his different film scores and his projects and things that he worked on that he collaborated with people,” Williams said “I think we can take from him his ability to bring people together to accomplish those things. I would honestly say, towards the middle of his life, you didn’t see a lot of people doing that. It’s always Quincy Jones and this person, that person, that person, which is great, because I feel like it’s something that he did to be able to bring all those people together, to be able to make those projects pop like that.”

Weinman said Jones’ collaborative approach not only brought established artists together but created opportunities for emerging artists to thrive.

“In ‘Back on the Block,’ there were a lot of people who maybe weren’t that known, and that really gave them careers, as many hits were on that album,” Weinman said. “It gave a lot of people a platform to be able to perform. That’s rare when you have a figure like him that gives other people a chance on that level. And this was at a time where I think things were going commercial in another way, where people were … trying to make people not what they are because they think it’s going to make money for them. I think he knew how to do something commercial and artistic at the same time.”

In addition to his music career, Jones was deeply involved in social activism. He co-founded the Institute for Black American Music to raise funds for a national library of African American art and music. He was also a supporter of Operation Breadbasket, a movement promoted by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference along with Martin Luther King Jr to improve economic conditions of black communities in the 60s.

Jones’ philanthropic efforts included the creation of the Quincy Jones Listen Up Foundation, which focused on building homes in South Africa and providing educational opportunities for disadvantaged youth. Jones also produced and conducted the 1985 charity anthem “We Are the World” which raised millions of dollars for famine relief in Ethiopia. Williams said Jones’ capability to collaborate shone through the “We Are the World” project.

“He used that platform, not necessarily celebrity status, and through his music and his connections with numerous people, he was able to get that message, which is what he did in [‘We Are the World’],” Williams said. “He brought so many performers together to do that. That was really amazing. I was just a small kid, but in the 80s, that was a big deal, using his platform to be able to reach areas that maybe somebody like me wouldn’t be able to do.”

Weinman said the impact of “We Are the World” was seen across the music community, with many eager to collaborate with Jones on the project.

“It spoke to all the different people who were involved in it,” Weinman said. “When you think of people in the artist community, people happily wanted to be part of this, because they saw that it was important. And you had somebody like Quincy who knew how to bring the right people together, had the right people around him to make it happen.”

Weinman said “We Are the World” became a cultural phenomenon that united people globally.

“It was huge, everybody knew that song,” Weinman said. “At the time, I was working in public schools with a nonprofit organization, and it was one of the things that school children were singing. It was an educational moment, a social moment; it was a global moment. I think when you think about Quincy and his social impact, that’s the piece right there.”

Weinman said a distinctive characteristic of Jones that stood out was his passion for creating music that was not merely for money.

“When we look back, when we think about quality, we should look back at people like Quincy Jones, like Michael Jackson, the work ethic that they had today in all facets, people who are true artists,” Weinman said. “We have to sort of fight against the people who just want to try to make money and try to put something out there … Quincy was behind the scenes, and he mentored these people. I mean, he mentored Will Smith. I think he was a father figure of a sort to Michael Jackson as well.”

Jones’ multidecadal career has meant his music has left a mark across multiple generations. Mikadze said he enjoys listening to Jones’ music to this day.

“Even now, when I’m on the road, I always put Quincy Jones albums on in the car for the ride, because it’s so smooth, it’s so tasteful, it gives you a good vibe, because few are like his personalities in his produced music,” Mikadze said.

Williams believes Jones’ versatility as an artist has meant his work has reached across a multitude of audiences around the world.

“He’s very eclectic,” Williams said. “He crosses over many different genres, it’s not just one. I think that in the world that we live in today that would be very greatly appreciated by an artist or a producer or arranger or composer [like Jones]. I mean, he’s literally all over the place, so I think that brings in more people to listen to his particular style, and not just certain cultures.”

Weinman said at the beginning of his career, Jones faced tribulations with finding success in his jazz band, but through his perseverance, he eventually became a household name and his legacy continues to inspire aspiring artists.

“It just speaks to the fact, If you’re really trying to be an artist, you have to be pretty savvy, you have to have courage,” Weinman said. “You have to stick to it. He stuck to his guns. He had all the tools to do what he did, and he believed in him.”