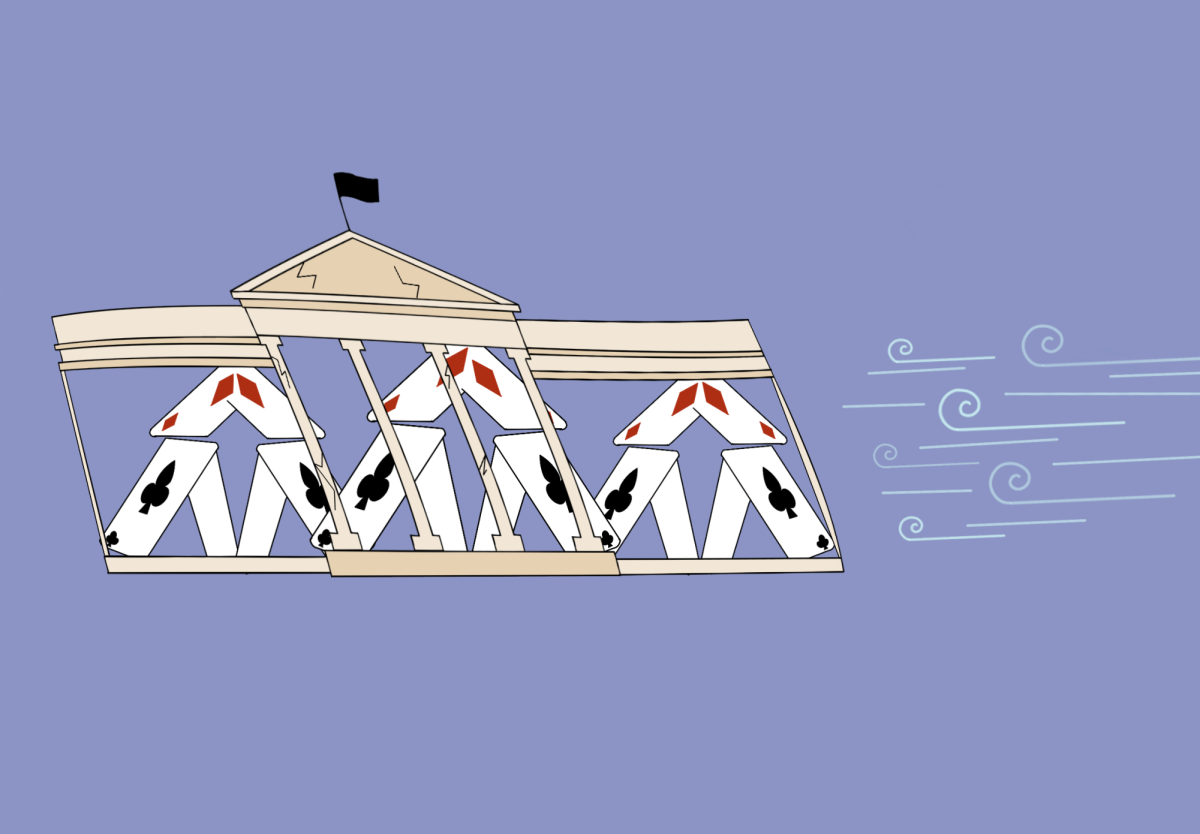

Public education has historically been seen as separate from the private sector. However, as more and more educational management organizations, which are for-profit entities, enter the business of operating charter schools, the line between the two institutions is becoming increasingly blurred.

During the 2011-2012 school year, seven educational management organizations operated at least one charter school in Georgia. Jarod Apperson, who analyzes metro Atlanta education data, thinks that allowing corporations to make a profit off providing students an education argue the latter.

“There is sort of an inherent conflict of interest between trying to be as cheap as possible in order to earn a profit and try ing to do everything you can to educate the students,” Apperson said.

Nancy Jester, a Republican running for state school superintendent, does not think that allowing companies to make a profit off providing educational services necessarily results in a lower-quality education.

“If [charter school operators] want to select a vendor to provide services to them, and if that vendor is a for-profit entity, I don’t have any issues with that,” Jester said.

Jester emphasized that many schools, both charter and traditional, rely on for-profit companies to provide services.

“Education in Georgia in our school districts is very much a for-profit endeavor for many vendors already,” Jester argued. “I mean, your school district contracts with people that sell them products from paper to pencils to textbooks to computers and those vendors make profit.”

Apperson, however, cites two APS schools, Atlanta Preparatory Academy, which closed in 2013, and Wesley International Academy, as evidence that allowing for-profit companies to run charter schools hasn’t worked in Georgia. Atlanta Prep was run by an Atlanta-based company called Mosaica Education up until its closing. Wesley was run by a company called Imagine Schools until its school board gained autonomy from the company and severed ties in 2012.

Andrea Knight, a parent of two students at Wesley, said Imagine had been overcharging the school for its building, which Imagine owned.

“The rent originally looked pretty reasonable, because it was based off what percentage of funding we got,” Knight said. “But to be a school, your funding is pretty low, because you’re not fully enrolled yet, you’re just starting. But as that grew over time, the rent went up to over a million dollars for a building that was not built to the code that APS was built to. The quality of the building was terrible.”

Knight said Imagine also charged “something around 20 percent of our revenue to provide services that they really didn’t provide.”

“It was really a struggle,” Knight said. “Salaries were low, supplies were in short demand, paper was treated like it was gold, the copier was under lock and key, because the resources were so strained.”

Atlanta Prep had similar problems with Mosaica. Neil Shorthouse, who was on the founding board at the school, said the board originally took a very hands-off approach to operating the school, allowing Mosaica to run day-to-day operations.

“We were operating under the assumption … that Mosaica absolutely knew what it was doing and would be very effective in running the school,” Shorthouse said.

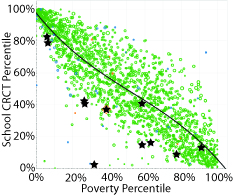

In an article for his blog, Grading Atlanta, Apperson wrote that Atlanta Prep’s students consistently ranked among the bottom in Georgia in terms of CRCT scores, and that only 36.2 percent of the school’s revenue from the 2011-2012 school year actually went to instruction. Shorthouse said the board was vaguely aware of the low test scores and questionable expenditures, but not the extent of them.

“We knew that we were paying high fees, but we were not totally alarmed by that,” Shorthouse said. “We thought they were high, but we didn’t think they were out of bounds.”

What ended up steering both schools away from their EMOs was a directive from the Georgia Department of Education that required that school boards be completely independent from EMOs.

As a result, Knight said, Wesley’s board was able to gain enough autonomy to end the school’s relationship with Imagine. In fact, according to a 2012 Atlanta Journal-Constitution article, Wesley is the third charter school in the state to sever ties with Imagine since 2010.

Shorthouse said that, after the state issued that directive, Atlanta Prep’s board “assumed full responsibility for the school and were much more aggressive in our prosecution of the duties in the requirements of the charter.”

Despite the progress Atlanta Prep’s board made in improving the school, according to Shorthouse, their charter was revoked by the APS Board of Education in 2013.

“We were, I’ll speak for myself, possessing a level of naivety that our charter management organization was absolutely all over this thing, and was gonna really run a terrific school, and I don’t think that they did,” Shorthouse said. “And then we found out, and when we found out, it was too late.”

Apperson argued that the problems Atlanta Prep and Wesley had with their EMOs are indicative of the inefficacy of allowing for-profit companies to manage schools. According to research he collected, EMO-operated charter schools have consistently underperformed traditional charter schools in Georgia.

“Every single one of [the for-profit charters], their students are scoring worse on the CRCT than you would expect based on the school’s free and reduced lunch percentage,” Apperson said.

Jester, when provided with the data Apperson collected, identified several issues with his categorization of “for-profit” and “non-profit” charter schools, writing in an email that “until the data problems can be resolved, it wouldn’t be prudent for anyone to make a comment or conclusion from the graph.”

Still, Apperson maintains that the test scores of EMO-operated charter schools have been much lower than what would have been expected based on their students’ socioeconomic level. He argued that for-profit charter schools take advantage of low-income students and parents who don’t have access to as much accurate information about schools as wealthier families do.

“A lot of these for-profit schools have targeted low-income communities in order to not have the level of scrutiny that more middle-class and upper-class people would demand from the school,” Apperson said.

Jester maintained that the structure of charter schools allows parents to “vote with their feet,” discouraging financial mismanagement.

“If somebody is mismanaging the money, if they’re not maximizing the utility of every dime at that school, and parents don’t like it, they can leave, and then that school will be shut down,” Jester said, “so there’s an incentive to maximize the utility in the classroom of every dime that comes into a charter school.”

Even so, Apperson insisted that for-profit charter schools can afford to provide a sub-par education because there are enough uninformed students coming in to fill any gap caused by dissatisfied parents pulling their children out of the school.

“There is an endless supply of students who are currently attending a school that they are not happy with or that their parents are not happy with,” Apperson said, “and so they’re moving to this school, but the school is not having to provide a good education because they don’t even care if the students come back the next year.”