Almost a year after 34 APS employees were indicted for their part in what The New York Times called “the most widespread public school cheating scandal in memory,” a total of 18 have pleaded guilty to their crimes. This leaves 15 educators to be tried if they never enter a plea. Of the 18 that have pleaded guilty, the majority are former teachers, with three former principals admitting guilt.

Almost a year after 34 APS employees were indicted for their part in what The New York Times called “the most widespread public school cheating scandal in memory,” a total of 18 have pleaded guilty to their crimes. This leaves 15 educators to be tried if they never enter a plea. Of the 18 that have pleaded guilty, the majority are former teachers, with three former principals admitting guilt.

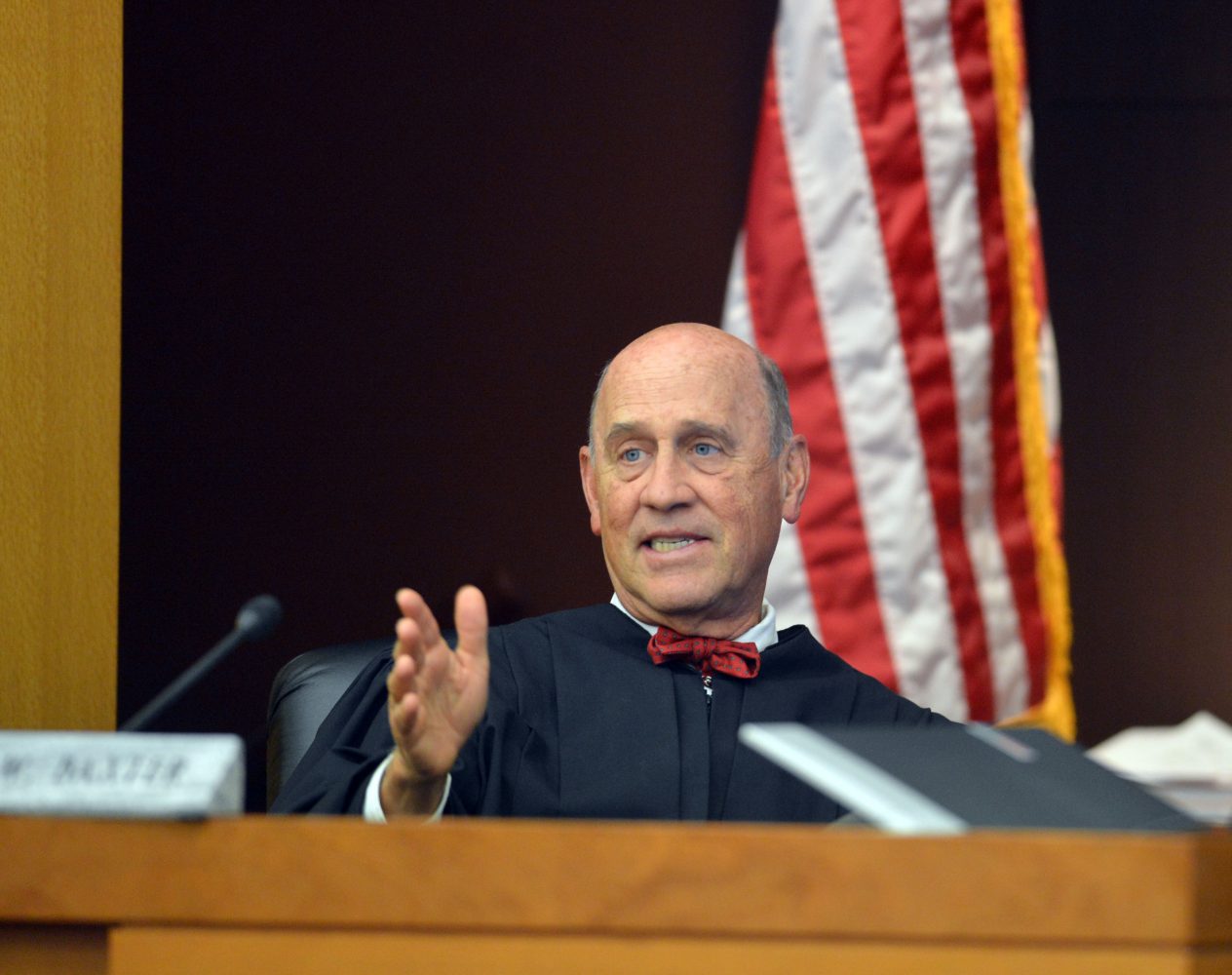

The way the pleas in this case have worked is as follows: the defendant and the prosecution negotiate a “deal” where the defendant pleads guilty but is given a lighter sentence than might otherwise result; then the prosecution and defendant report to a hearing where the prosecution presents the “negotiated plea” to the judge, Grady graduate Jerry Baxter, after listing the charges against the defendant; finally, the judge can either accept or reject the plea. If the judge rejects the negotiated plea, the defendant can withdraw his or her plea and go to trial. If the judge accepts the plea, the defendant reports to the probation division and starts serving the sentence.

Thus far, all of the defendants have entered First Offender pleas, all of which Baxter has accepted. Enacted in 1968, the First Offender Act allows people with no criminal record to request that the judge sentence them under the Act, which means that, after the defendant has completed the terms and conditions of their sentence, they do not have a criminal conviction on their record. The downside to this method of sentencing is that, if the person violates any of the terms of their sentence, they can be re-sentenced up to the maximum allowable penalty.

The majority of the teachers who have pleaded guilty have reduced their felony charges to misdemeanors, resulting in sentences of 12-24 months probation, 250-350 hours of community service and paying restitution in the amount of any bonuses they received. By far the most severe sentence that has been proposed is for APS former Chief Information Officer Jerome Oberlton, who pleaded to the felony charge of receiving large kickbacks. Oberlton’s sentence will be finalized on March 24, but he could receive 41 months in prison, pay $735,130 in restitution and perform 1,000 hours of community service.

Though more than half of the defendants have pleaded guilty, the judge has extended the deadline for negotiated pleas to Feb. 17. Defense attorney Don Samuel suspects that he will continue to accept pleas even after that date. Samuel believes that the number of remaining defendants will get down to below 10 before the April trial date, meaning that the trial will be able to be held in the Fulton County Courthouse, rather than the Atlanta Civic Center that was once being considered.

On Jan. 6, when Baxter accepted six of the more recent guilty pleas, he required all the defendants to be present in the courtroom to observe the proceedings, which included not only presentations of the charges against each defendant, but also reading of letters of apology from each employee who pleaded guilty. The mood was somber. Samuel speculated that Baxter’s intent was likely to force all the defendants to consider their actions, the effect on their students and to promote the entry of more pleas. It remains to be seen just how effective that strategy will turn out to be. Certainly the leniency of the sentences imposed as part of the negotiated pleas, versus the much more severe possible outcomes from a trial, have been striking, and could be quite persuasive to those with charges still pending against them.