The High Museum of Atlanta is currently displaying “Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina,” which showcases ceramic objects created by enslaved African Americans in the Edgefield region of South Carolina and Georgia, in the decades preceding the Civil War.

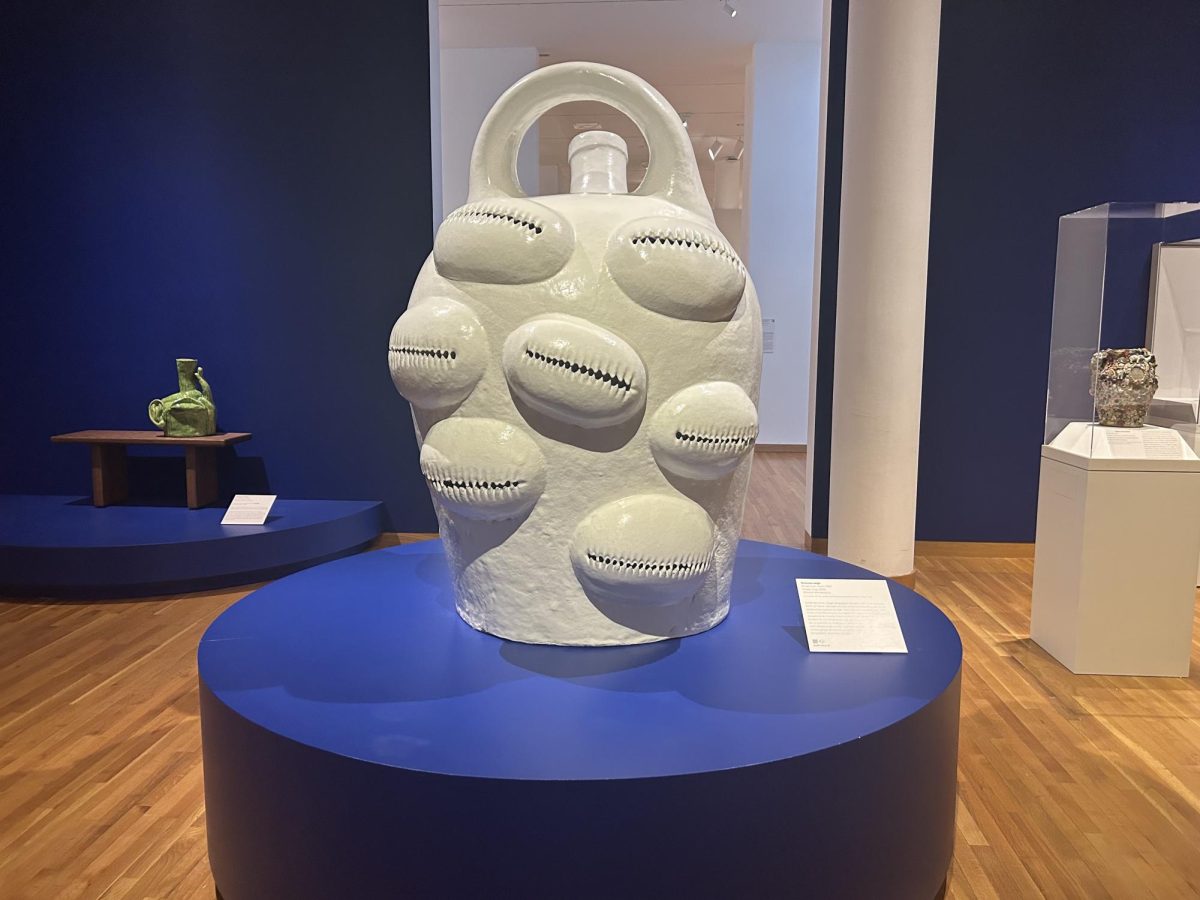

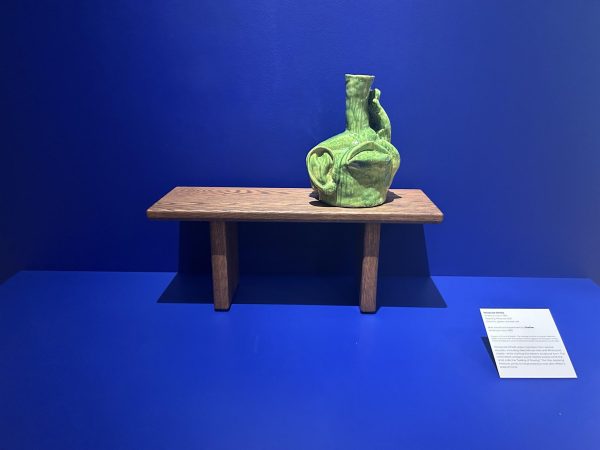

The exhibition consists of nearly 60 ceramic objects ranging from jugs to face vessels, each of which reflects the lived experiences, creative agency and material understanding of the enslaved persons who created them.

“It is about the important innovations in ceramics made by potters who were enslaved in Old Edgefield, South Carolina in the 19th century,” said Katherine Jentleson, High Museum curator of folk and self-taught art. “The pottery created there is unlike anything that had been produced in the United States up until that point. Its legacy, including that it was made in bondage, demonstrating the resilience of creativity and the human spirit even under the harshest conditions of enslavement, continues to inspire artists who are working today.”

The “Hear Me Now” exhibition was organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where the exhibition was previously held before traveling to Atlanta. The High Museum’s production of “Hear Me Now” is the sole southern venue.

“The show originally came out of the research conducted by Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Adrienne Spinozzi,” Jentleson said. “She observed the scarcity of examples of southern ceramics in the Met’s collection, including works made in Old Edgefield, South Carolina, and began looking for and learning about this important tradition.”

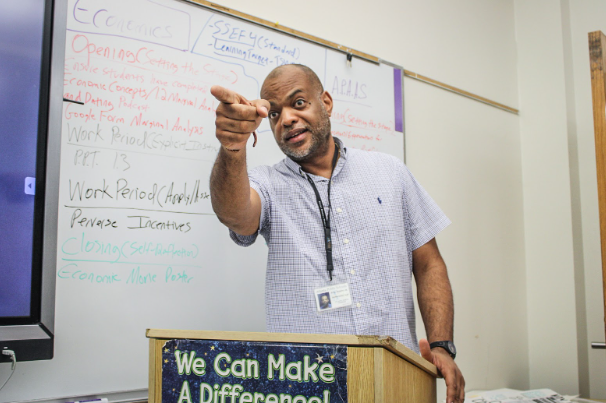

Jason Young, co-curator of “Hear Me Now,” said the exhibition has been displayed in various art museums across the country to spread awareness of widely-unknown material about enslaved persons in the South during the Antebellum period.

“The curatorial team was interested in providing more access to this material, which is somewhat familiar in the South, and especially in South Carolina, and we really wanted to amplify the story and to give people in different parts of the country access to it,” Young said. “This is one of the reasons why we were really keen on having a touring show, and opened up the MET Museum, which made this material available to a vast global audience.”

Young said the exhibition was intended to be held at the High Museum in Atlanta, in consideration of the exhibition’s significance to the local region.

“It was very important to us from the very beginning to make sure that there was a southern venue to make sure that this material comes home,” Young said. “One of the things that The High Museum was able to do, which I think, supported the show in a really fantastic way, was that they brought some of the other decorative art materials that they have in their possession and brought it into conversation with this ceramic material.”

Young said one of the goals of the “Hear Me Now” exhibition is to expand the collective understanding of American slavery by highlighting a sector of slavery that is widely unknown.

“It’s an exhibition that features a story about American slavery that is somewhat different,” Young said. “We often think of the American slave past as one that’s based in agricultural production. The story about cotton and sugar and indigo has taken up so much space in the way that we think about the slave past that we don’t imagine that there were different experiences for enslaved people. And one of the things that the show does is think about the various ways that enslaved people are engaged in the productive engines of the U.S. economy. Here, enslaved people were not so much engaged in agricultural production as they were engaged in industrial level production of ceramic materials.”

Ayana White, who works at the High Museum as a security officer for the “Hear Me Now” exhibition, has noticed that the exhibition has attracted many Southerners.

“What I’ve seen so far is that we have gotten a lot of people from South Carolina or people who’ve grown up in the South come here, and they’re like, ‘Oh, I didn’t know this,’” White said. “I feel like [the exhibition] will open more people’s eyes to another part of slavery that we really don’t get to hear about.”

Young said enslaved potters made a measurable contribution to the economy of the South prior to the Civil War.

“This material was absolutely essential for the proper maintenance and operation of slave plantations, and so the ceramic material that was produced in and around Edgefield was then shipped throughout the South,” Young said. “It was used as part of the productive machines of southern plantation, and so, the legacy of this material is very much a part of the story of the antebellum period.”

Young hopes the exhibition will allow viewers to grasp the artistry embedded in enslaved practices in the South.

“I hope that it expands our understanding of the slave past,” Young said. “I hope that it amplifies the role that enslaved people played, not only as producers, but also as artists. One of the things that is very clear, and in the show is that there’s real artistry involved in this material production.”

In recognition of the influence of works of enslaved potters, the exhibit also features art from contemporary artists who have gained inspiration from these works. Such artists featured include, Theaster Gates, Simone Leigh and Woody De Othello. In addition, the exhibit highlights a prominent enslaved potter engaged in ceramics known as Dave.

“Dave was a really fantastic potter, who was not only making magnificent pots, but was also literate, and was signing, dating and inscribing poems on the sides of the pots that he’d made,” Young said. “And one of the things that’s clearly evident in those poems is that he’s a part of a really big world of ideas. He’s communicating ideas and sentiments on the sides of those pots that clearly mark with inspiration that exceeds the plantation.”

Jentleson said Dave’s work has been impactful for many viewers, highlighting the creative triumph of enslaved potters’ work amid the cruel conditions they faced.

“We want to emphasize the extraordinary achievements of a potter like Dave but also acknowledge that the enterprise of making pots — making the clay, building the kilns, keeping them burning — was the labor of many who developed specialized knowledge and roles within the process of making,” Jentleson said.

Young said the exhibit embodies a theme of resiliency, reflecting the hardships of the enslaved potters’ crafts.

“They’re working in a system that operates in violence and the threat of violence,” Young said. “Even as they’re engaged in this productive material, it’s clear that they’re working under extreme forms of duress and threat. And that would be true of enslaved people, no matter where they were working, so, I think that actually potters share that experience.”

Jentleson believes the exhibition serves as an opportunity to demonstrate some of the South’s contributions to American art.

“The South is often taken for granted in histories of American art, as are the productions of Black Americans,” Jentleson said. “So, this show has an important resonance in our region and in a city where the cultural triumphs of Black Americans are especially resonant.”