Marietta City Schools removes two dozen books from library, receives community backlash

The Marietta school board voted to remove 23 books from Marietta High School’s media center after complaints of “sexually explicit” content brought by Superintendent Grant Rivera.

This removal quadrupled the number of books removed in public high schools in Georgia, from previously seven in October 2023 to over 30, according to PEN America. Five of the 23 removed books are on the most challenged books in 2022 list of American Library Association, and six are on the organization’s list of 100 most banned and challenged books in the 2010s.

Marietta senior Wesley Harrison believes book removals are a complicated issue, and some books were more justified than others for removal.

“I believe that there are some books that we don’t really need in the high school library,” Harrison said. “We have high schools that cover a large range of ages, from 13-year-olds to 18-year-olds. I think that books are a powerful tool for control of people. They are a force for censorship, but at the same time, we do need to consider the fact that we have a variety of ages that we’re appealing to, and try to make sure that that’s appropriate for all of them.”

In December, the school board asked Superintendent Grant Rivera to look through current library selection district-wide, and he came back with a presentation deeming 23 books in high schools “sexually explicit,”and proposed their removal at the December school board meeting.

Harrison believes students should have been involved more in the removal process.

“I interviewed many students in the process of covering this topic for our newspaper (The Pitchfork), and a lot of them either knew nothing about what was happening or just the very basics that books were being removed,” Harrison said. “There was no student participation in any challenge throughout all the books that had been discussed.”

Marietta senior Sydney Martinez said this highlights a flaw in Marietta schools’ removal procedure.

“We are the ones reading the books, not parents,” Martinez said. “Not in any step of the Board of Education’s review process was a student allowed to give their opinion on any book; we are only allowed to appeal a decision for a book after the fact that they were pulled from our library.”

Junior Alexandra Marshall co-founded the Banned Book Club at Midtown and believes students need to be part of any book removal process.

“Students are the ones affected by change in content in high school libraries,” Marshall said. “It is a rob of our rights to remove books without having us in the conversation. If this was to occur at Midtown in this manner, I would feel extremely unvalued as a student in an environment meant to learn.”

Additionally, Marietta High School’s media center references the American Library Association’s “Freedom to Read” on its home page, stating “Libraries should challenge censorship in the fulfillment of their responsibility to provide information and enlightenment.”

Midtown English teacher Kate Carter believes it is the job of school libraries across the country to fight against censorship in their districts.

“I think that book bans and removals can be really dangerous,” Carter said. “I think when books are banned in different places, it’s creating a near dystopian society. Where people are scared of ideas and thought experiments, people become scared of learning about stories that are unlike their own. It’s a terrible slippery slope that we all need to work to avoid.”

The school board’s motion to approve the superintendent’s recommendation raised some concerns among faculty and students. Harrison recalls classmates arguing to appeal the book removals.

“The situation started to heat up more in the December board meeting when the list of books was officially released and books were officially removed,” Harrison said. “We had a student petition against it, and the conversation really heated up against it.”

Between Dec.12, the date of Rivera’s proposal, andJan. 16, there was a period called “Sunset Directive” when community members could appeal the motion to the school board. At theJan. 16 board meeting, a group of parents presented against the proposed removals but the board voted 6-1 to remove the books.

A parent-run organization, Marietta In The Middle, was established to bring the 23 appeals to the district.

“The biggest losers in this whole book-banning debacle are the students who have lost some important books from their media center that speak to their lives and experiences,” Marietta In The Middle said in a statement after the meeting. “Parents are angry at having their desire to be the ones making choices in reading materials for their children co-opted by this school board, and community members are embarrassed that our school system is now the leading book banner in the State of Georgia.” Did you try to speak to someone with this group rather than just quoting from a statement? If not, please do so and use that comment, as opposed to a statement here.

There were additional parents in support of the removal, many of whom were representatives from Moms for Liberty, a nationwide organization with a mission to “fight for the survival of America by unifying, educating and empowering parents to defend their parental rights at all levels of government.”

“I think people are feeling a need to be more responsive to their community,” Midtown media specialist Brian Montero said. “I think communities are starting to want to have a voice in their school, which is valid, but I think if they do want to challenge books, they should really have a rationale why they have the book and be open to a dialogue with the community about what they want to see change.”

Fifty six percent of the 23 books discuss homosexual topics. Critics have accused the district of targeting books with LGBTQ+ characters.

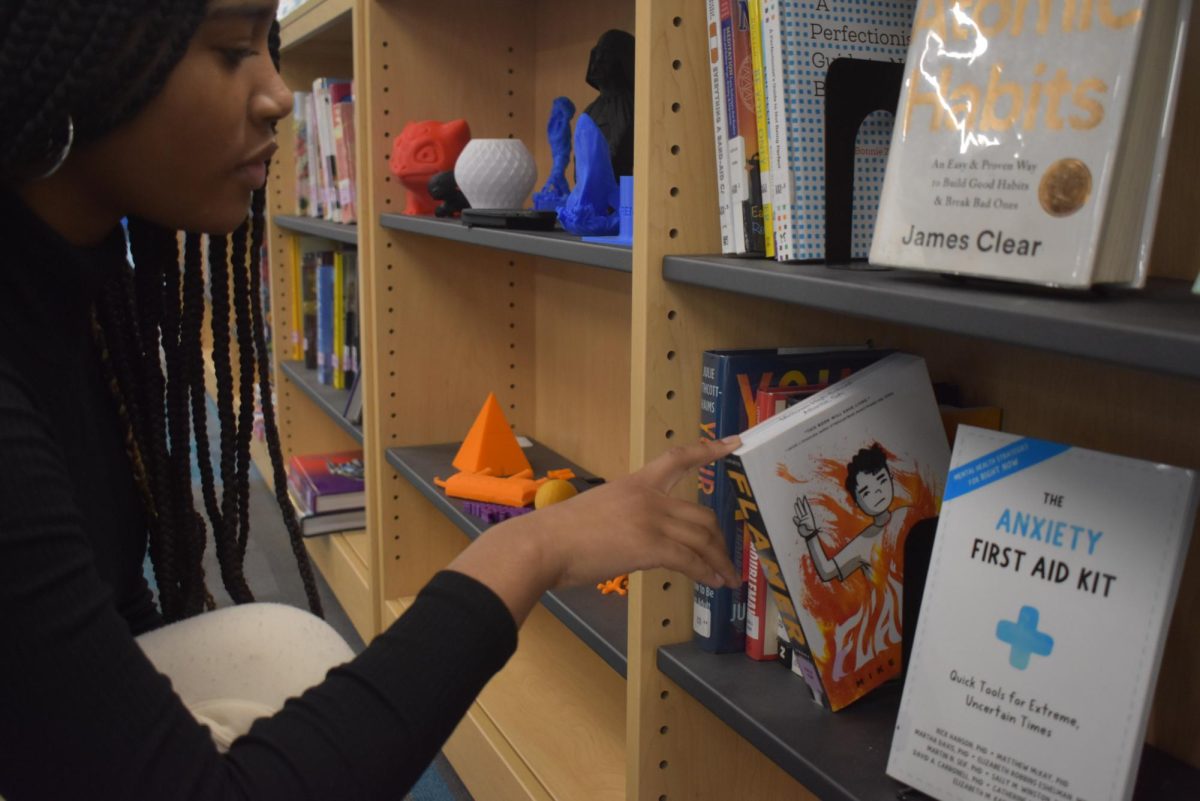

Harrison is a member of the LGBTQ+ community and feels some of the removals provided valuable stories to queer youth, including “Flamer” by Mike Curato, which tells the story of a young gay middle schooler navigating social circumstances.

“‘Flamer,’ which is one of the first books brought to our district for removal, serves a purpose to speak on someone’s experience,” Harrison said. “It’s not something that’s supposed to be overly graphic, but rather an attempt to show true life experiences of people our age. And I think that it’s frankly a little demeaning to us, as young adults, [denied] representation of those experiences in that way.”

Marshall believes that book removals with LGBTQ+ content can be harmful to students.

“It starts with the books,” Marshall said. “Removal of books with this content sends a message that ‘You are not welcome here.’ The last thing we should be doing as a district is limiting speech that can uplift students.”

In the past year, there have been 30 book removals and bans in Georgia, 23 of which were in the Marietta district.. Some counties, including Coweta, Forsyth and Floyd, have added parental consent requirements or “M for Mature” stickers to certain titles. Harrison thinks a harmful precedent has been set other school systems in Georgia.

“Students have protection under the First Amendment, and I truly think that we do not have the same protections that are in our community space,” Harrison said. “If we start with our books being censored, it could ultimately lead to our speech and our free thought being censored.”

In April 2022, Gov. Brian Kemp signed Bill 226 allowing parents to request the removal of a book from school libraries, which enabled Marietta’s parents. Midtown Reading Bowl champion Carmela Marra hopes this trend does not come to Midtown.

“A lot of times, I think there’s political and personal motivation behind the books that they’re banning,” Marra said. “In this case, many who were about LGBTQ don’t think there’s really much of a line of what students shouldn’t be exposed to currently, and bans are widely being based on personal opinion.”

Carter said she feels safe as a language arts teacher, and spearheaded a project in her AP English Language and Composition course last year to discuss the rhetoric of book banning.

“I haven’t ever had a complaint about anything that I’ve had students read,” Carter said. “It’s one of the great things about being a teacher in this school; I feel very protected. I do think that if somebody complained, there would be a lot of pushback, both from the school and the school district.”

Montero shared these sentiments and has not heard any complaints about library content within the schools. Midtown’s media center has several of the removed books in Marietta, including “Flamer” and “Perks of Being A Wallflower.”

“This is sort of a new phenomenon for high school libraries, and we are very lucky here to have a uniquely open community,” Montero said. “So, I think other communities are more sensitive to this shifting culture, but we are working to choose books [as media specialists] for the community that don’t necessarily reflect what we think.”