In an effort to reduce the amount of time students spend in the bathroom, many teachers have resorted to giving students extra credit incentives to save their bathroom breaks for in-between periods. Not only do these policies punish students who don’t skip class in the bathrooms, but they have limited success at fixing the real problem.

It’s a common problem at Midtown: students leave class to use the bathroom, only to not return until the period is almost over. Different teachers implement different strategies to try and mitigate the issue with varying degrees of success. Some require students to leave their phones in the classroom while others ask that students are back in a certain amount of time. Most of these measures are harmless, as they don’t actively encourage students to not use the bathroom, rather they’re meant to ensure that students come back. Incentives to not leave the room at all, however, are far from benign.

According to the Urology Care Foundation, forcibly holding bladder or bowel movements can lead to an unhealthy bladder, along with a wide range of health problems, including urinary tract infections and bladder pain. When students are incentivized with extra credit on their next test, quiz or assignment, they are forced to follow unhealthy habits during the school day.

Not only are these kinds of incentives a detriment to students’ health, but they also unfairly punish the students who aren’t part of the problem. Those who use bathroom passes responsibly during class are forced to either hold it or lose extra points on their future assignments, and this loss is a powerful motivator.

According to The Decision Lab, fear of loss is nearly twice as powerful as a desire to gain in motivating our decisions. This, combined with some students’ hyperfocus on grades, creates an environment where students who’ve done nothing wrong will avoid using the bathroom so that they don’t give up their extra credit.

Students skipping class in the bathroom is still a problem that needs to be addressed, but incentives to not go at all should not be a part of the solution. Teachers should continue to implement other strategies that are already in use, such as taking phones and setting time limits.

If these methods are ineffective, new ones can be developed. For example, teachers could implement a sign-in, sign-out system, where students note the time when they leave and return to class. These time charts can be given to administrators at the end of each week, and used to hold students accountable for unreasonably long absences.

Furthermore, extra credit incentives have limited success at combating extended bathroom breaks among the students they’re targeted towards. They discourage students from leaving the room in the first place, but they do nothing to keep students in check after they’ve walked out the door. If a student wants to cut class, they can just forfeit their extra credit and leave anyway.

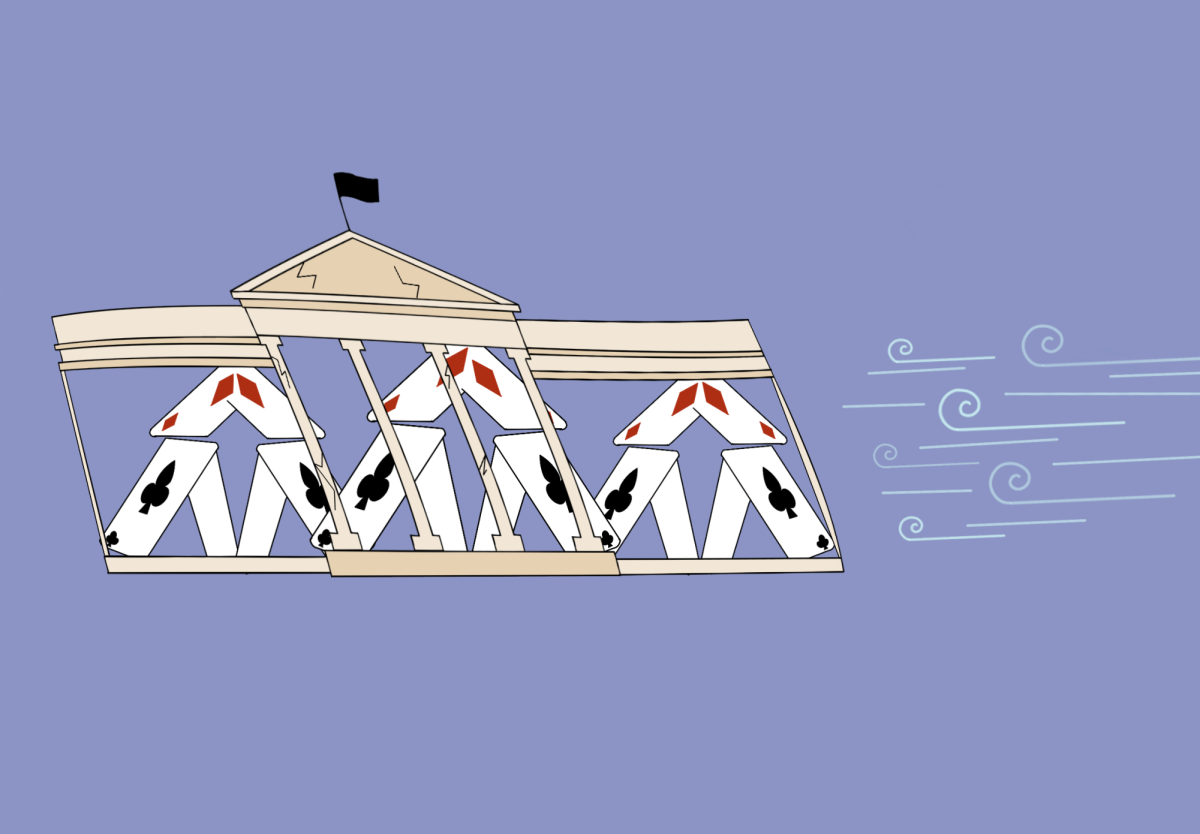

While a key component of these policies is a limited amount of extra credit/bathroom vouchers, this too is ineffective. Even after all their passes have been used, it’s tough for teachers to argue that students don’t need to use the bathroom if they say that they do, and often students are allowed to leave the room anyway.

Encouraging students to never go to the bathroom during class is the wrong way to solve Midtown’s bathroom troubles and is not only harmful to many students, but is also entirely ineffective. Instead, teachers and administrators should focus on solutions that don’t discourage students from practicing basic personal care.