Racial diversity is always a hot topic; it seems every other week, new measures are being implemented in universities, workplaces and neighborhoods to ensure a racially-diverse environment. Despite this, one of the biggest causes of diminishing racial diversity in Atlanta Public Schools is never questioned: charter schools.

APS is home to 19 charter schools, making up just over 20 percent of all schools in the district. Rather than being overseen by the Board of Education like public schools, charter schools are independently run. Essentially, they are an outsourced form of schooling that handles much of their business outside the scope of APS oversight. In spite of this separation, charter schools still receive public funding.

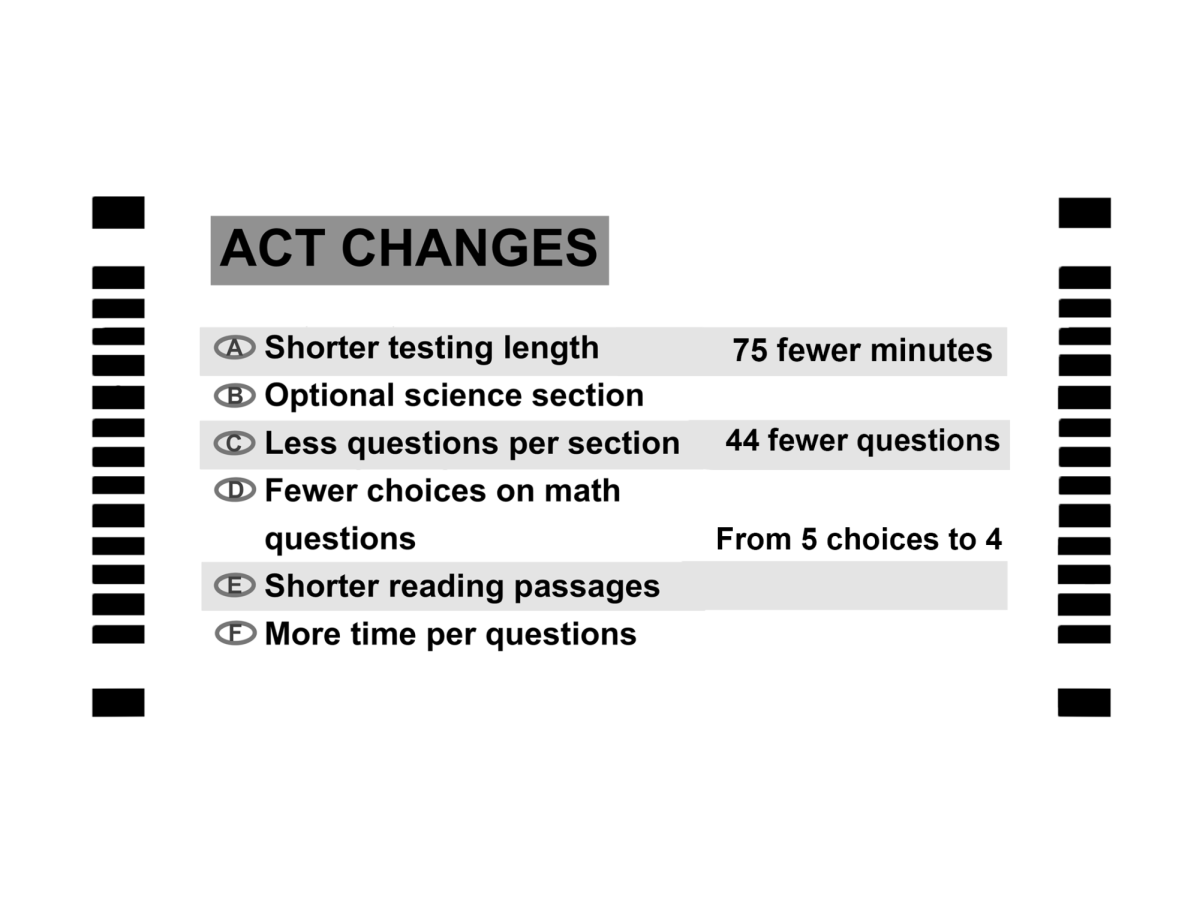

Charter schools are often marketed as a better, more effective alternative to public schools. While the higher test scores in these schools may seem to support this claim, this doesn’t hold up to scrutiny. In actuality, the difference in test scores has nothing to do with more effective schooling, but with a higher economic class. There is a well-known correlation between wealth and higher test scores. In fact, this correlation is so strong that test scores can be predicted based on a group’s economic makeup. Using these predictions provided by APS Insights, it is clear that most Atlanta charter schools actually fall below the levels of state test proficiency predicted for their economic status.

Not only do charter schools not hold up to their claims of improved education, but they actively harm public schools around them. Charter schools draw the more motivated, higher performing students out of schools that are often underperforming already. This creates underfilled, underperforming schools and results in an inefficient use of APS’s already limited budget.

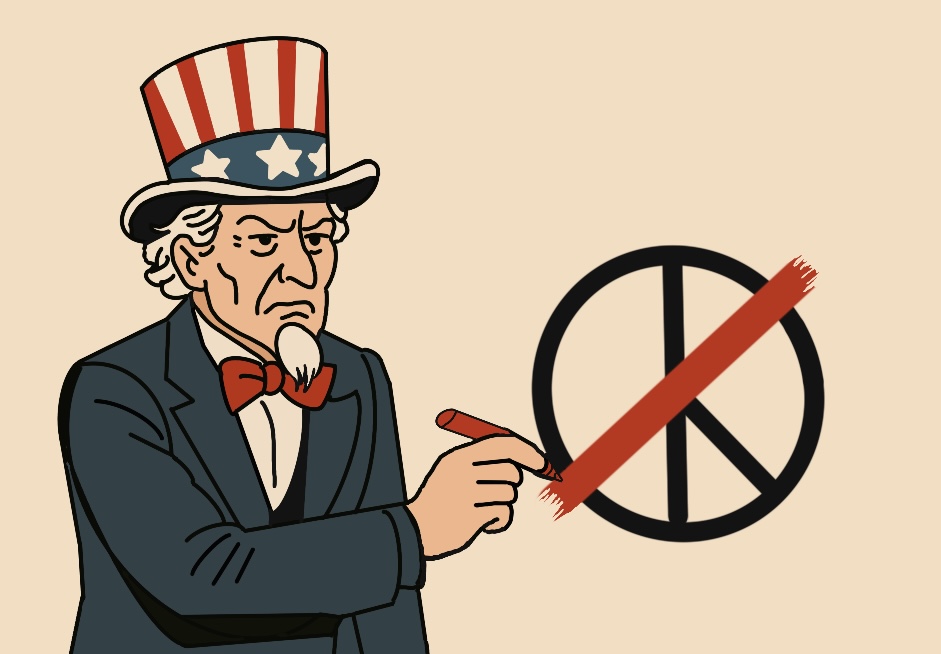

In addition to separating economic classes, charter schools also contribute to the creation of racially homogenous schools. Race is inextricably tied to wealth and likely will be for the foreseeable future. When charter schools draw affluent students away from their neighborhood schools, they often create a system of de facto segregation, where affluent and predominantly white charter schools contrast with poor and predominantly black public schools. The lack of diversity promoted by charter schools has become such a well-documented phenomenon that the NAACP has even come out with a direct rejection of this schooling model, stating that it fails to equally serve the disadvantaged children it advocates for.

There is some argument for the existence of charter schools, as they represent a valiant effort to give motivated students a better environment to raise themselves out of poverty. However, they also contribute to the problem they were created to solve. While charter schools exist as an attractive alternative to the underperforming and often underfilled schools they are near, they only make the problem worse by taking away the most successful and affluent students.

Denying motivated students the opportunity to go to a better school is no easy decision to make, but granting their wish condemns other students to continue attending “failing” schools. The cycle needs to be broken at some point, and unless APS stops avoiding real solutions by giving more affluent, better test scorers a way out, it will only continue. In order to provide equal opportunities for all students and improve the failing state of many of its schools, APS needs to stop funding the charters that draw the life and funds out of neighborhood public schools.