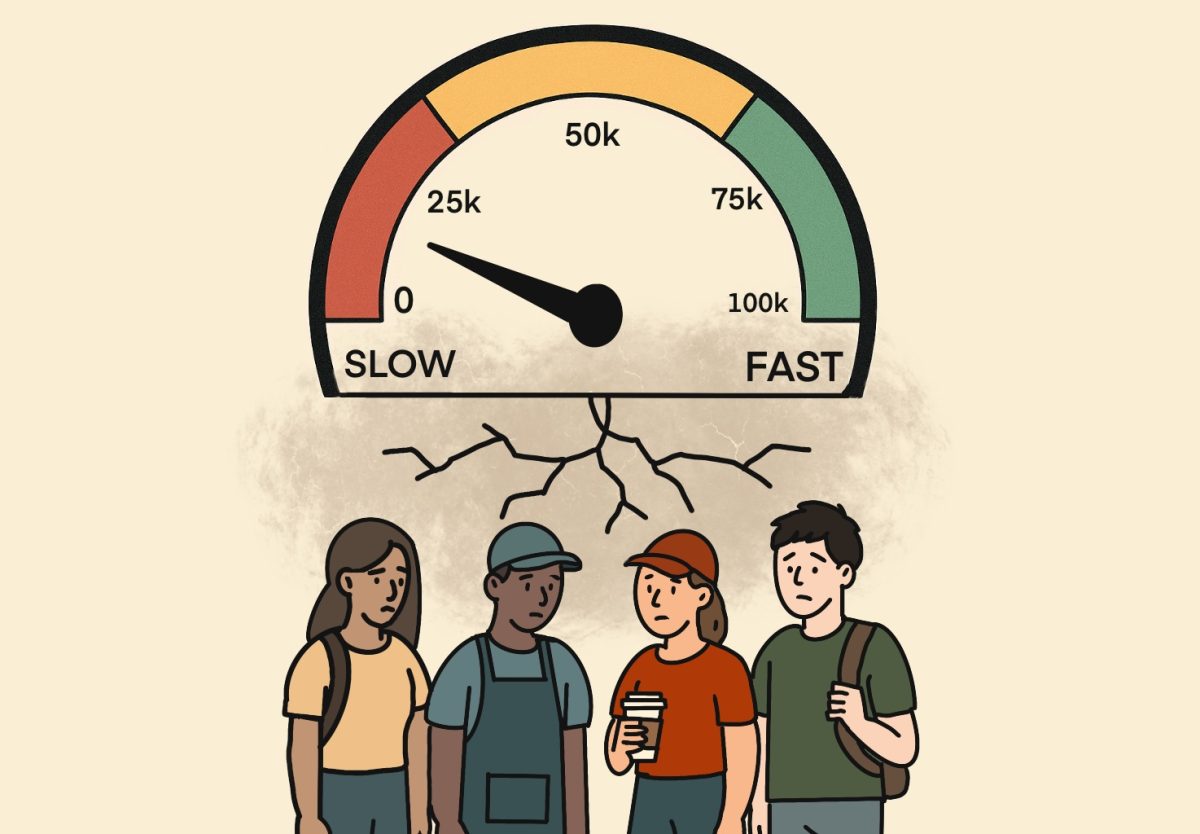

To reduce excessive speeding in school zones, Atlanta Public Schools and the city are placing speed cameras near several schools.

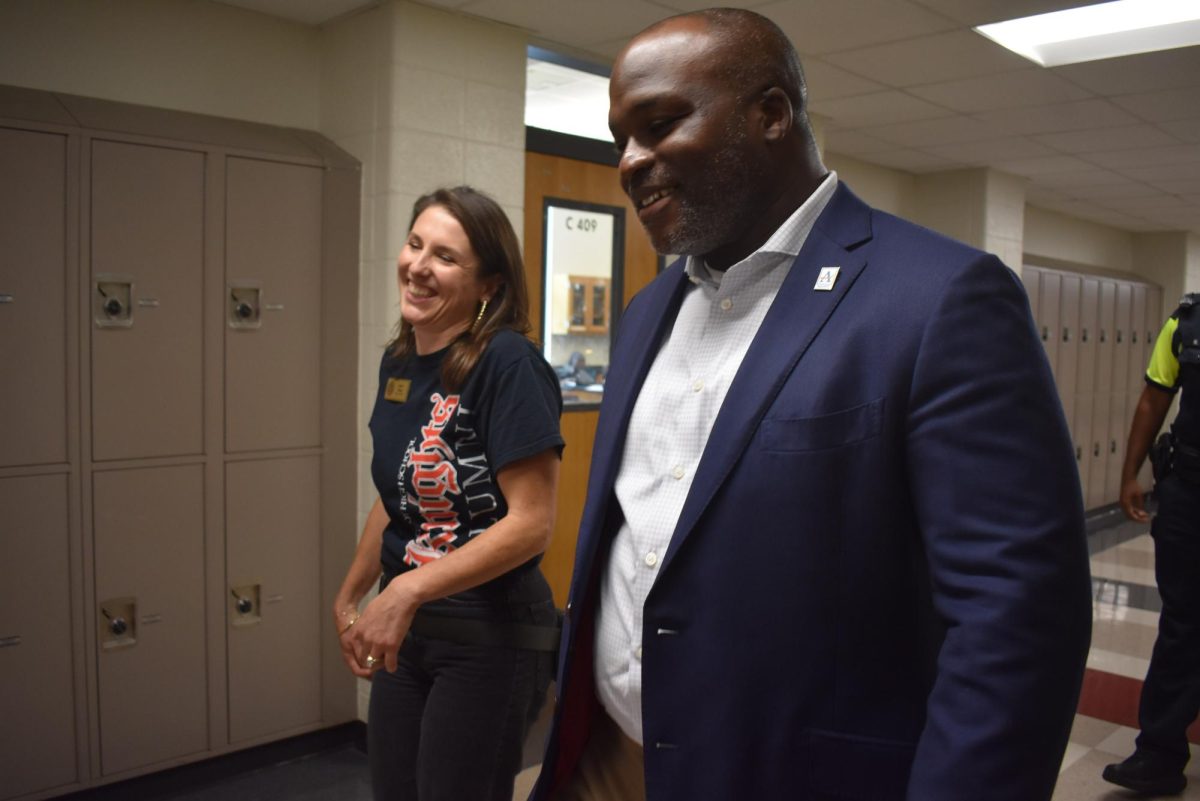

APS Police Chief Ronald Applin said the program’s purpose is to protect students walking to and from school from speeding drivers.

“We have had two kids who were killed in school zones since I’ve been the chief of police,” Applin said. “So, one of the things that we wanted to do is try to get people in school zones to slow down. If you drive slower and someone steps into the street, you have a greater chance of stopping, and even if you hit someone, you’re less likely to cause more severe damage to that person.”

The program will roll out in phases and first launched in August at 10 APS school sites: Burgess-Peterson Academy, Cleveland Avenue Elementary School, Continental Colony Elementary School, Drew Charter Schools, E. Rivers Elementary School, Kindezi at Gideons Elementary School, Kimberly Elementary School, Miles Elementary School, Brandon Elementary School and Fickett Elementary School.

The first phase was a warning period, in which anyone with a speeding violation – driving 10 or more miles over the speed limit – was issued a warning. Individuals who violated the speed limit were issued speeding tickets starting on Sept. 16, with the first violation being $75 and subsequent ones worth $125.

“The company that we’re working with – Verra Mobility – did a study of every school zone, and based on that, we picked the most severe first, and less severe last,” Applin said. “However, some roads were not certified by the state to be able to run speed detection, [so] we had to go back and just go with the ones that are certified. We’re working to get the other roads set up, so as they come on board, we’ll probably just pull in those roads and do 10 [schools] at a time.”

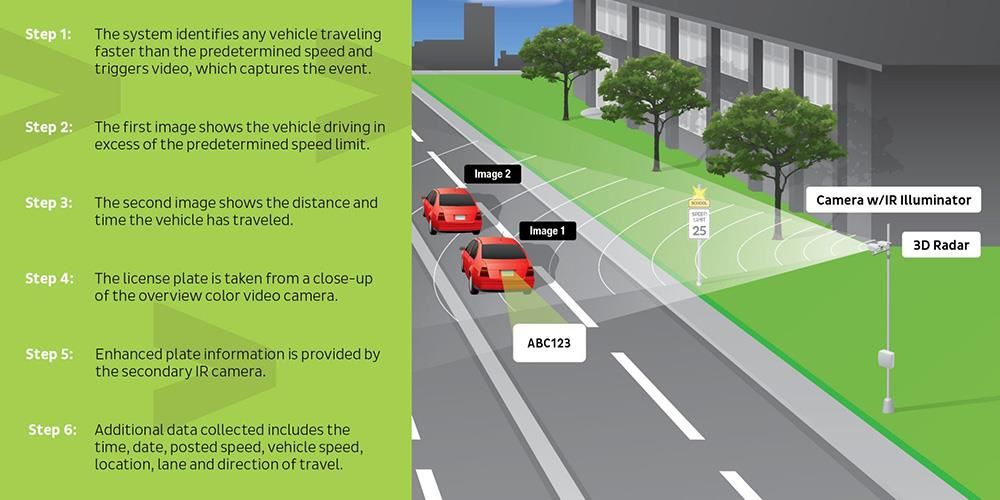

The system identifies any speeding vehicle by video. The cameras will detect the license plates of speeding cars, and this information will then be sent to the Atlanta Police Department which will confirm the violation and mail the driver a ticket.

“Just think about the fact that we’re looking at speed [and] the road; we’re not focused on screening kids coming into the building or cameras monitoring kids inside the building,” Applin said. “It is significant in that we’re now focusing on the exterior roadway access for students to the school. I know we’ve gotten a lot of warnings that have gone out already, so we’re getting ahead of it; if people start slowing down, we’ll definitely see the fruits of our labor with this.”

Rick Baldwin, president of the East Lake Neighborhood Community Association, believes over time, the program will improve student walkability and safety around Drew Charter.

“Eastlake is a residential neighborhood, so a lot of kids walk to school, and dealing with the pedestrian traffic is a big issue,” Baldwin said. “I think that these cameras will have a serious impact on the improvement of safety of the pedestrians and the kids going to walk into school.”

E. Rivers Elementary parent Allison Nelson walks her daughter to school every day and crosses the intersection between Peachtree Battle Avenue and Peachtree Road, where police said there have been at least 22 crashes since last year. She said the uniqueness of the program will improve pedestrian safety.

“Drivers will pull into the crosswalk before coming to a complete stop, and we also experience oblivious drivers that honk despite pedestrians in the crosswalk or that are not paying attention,” Nelson said. “The program is more significant than the posted ‘School Zone’ signs and lights because it comes with actual consequences for speeders when APS or APD officers are not available to patrol and ticket. I feel like people will most likely be more cognizant of their speed knowing they could get a ticket or have received one.”

Greyson Forster, president of Midtown organization Atlanta Students Advocating for Pedestrians, agrees with Baldwin and believes the safety program is important to encourage more students to walk or bike to school.

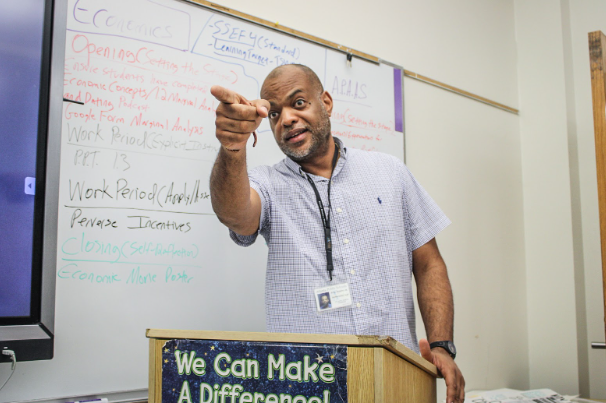

“Safety is a huge deal; in 1969, 48% of children five to 14-year-old walked or biked to school, and then in 2009, that [statistic] fell all the way down to 13%,” Forster said. “That’s a mix of people being further away from school, but also [walking] becoming more dangerous in the light of bigger vehicles. Nowadays, more people drive SUVs with poor visibility and have a higher fatality rate for pedestrians, and they drive faster, so parents may not feel comfortable walking with their kids.”

However, Forster said locating the cameras only in school zones limits their scope and impact on students who live outside the school zones.

“Since 2018, speed cameras can only be used in school zones, and so it takes a lot of permitting and work with the state to actually get these done,” Forster said. “So, [the program] is not going to make a massive difference for kids living outside of school zones until Georgia legalizes the speed cameras to be used for enforcement, city-wide and much more.”

Baldwin said although the safety program is supplementary to existing safety precautions near Drew Charter, it is unique because it has a penalty.

“Changing people’s behavior only goes so far unless there’s a penalty involved,” Baldwin said. “So, the penalty is going to be a ticket and a fine, and I think it’s going to be effective because there’s a cost to pay; but you don’t change behavior unless there’s a cost to pay.”

Additionally, the partnership between APS, the city and contractor Verra Mobility will not cost the district. The safety cameras will be funded by a percentage of the paid fines collected through speeding citations, and will possibly fund future safety projects around the district.

“I think the [stipulation] is good; more schools need [this safety program] because most schools are not in some quiet residential area,” Baldwin said. “They’re usually in a high-traffic area and not in little quiet cul-de-sacs. There are drivers out there who are insane, so they need to be reined in, and these programs are needed.”

The city is also working to gain authorization from the state to expand the program to additional APS schools. Forster believes the program could benefit Midtown.

“Midtown is boxed in by the city’s high injury network, which is a small number of streets that account for a vast majority of deaths and injuries,” Forster said. “So, hopefully, slowing cars down before we can actually implement some of the plans (street changes) that can help accelerate progress.”

Baldwin said the program will allow more students to safely and freely walk to or bike to school.

“[The program] is going to impact students because it’s going to make the area around the schools safer,” Baldwin said. “I think that the people who live close enough to school should be walking or cycling to school anyway; we don’t need more cars. It’s a densely populated city to begin with, inside the city limits. If you make the areas around the school safer, then people will consider non-vehicular transportation more, and that’s what we need as a city for the future.”

John • Nov 3, 2023 at 10:48 am

For the most part, automobile drivers don’t even think about the posted speed limit unless they see a cop. While Texan drivers will drive in the triple digits on a residential street, most other drivers slow down when the street doesn’t feel comfortable to drive fast on. Certain factors, such as lane width, bends in the road, and the closeness of buildings and trees, impact what speed drivers feel comfortable driving at.

To the one person who notices this comment, I would recommend that you exercise your role in democracy while equipped with the knowledge that design is more effective than enforcement.