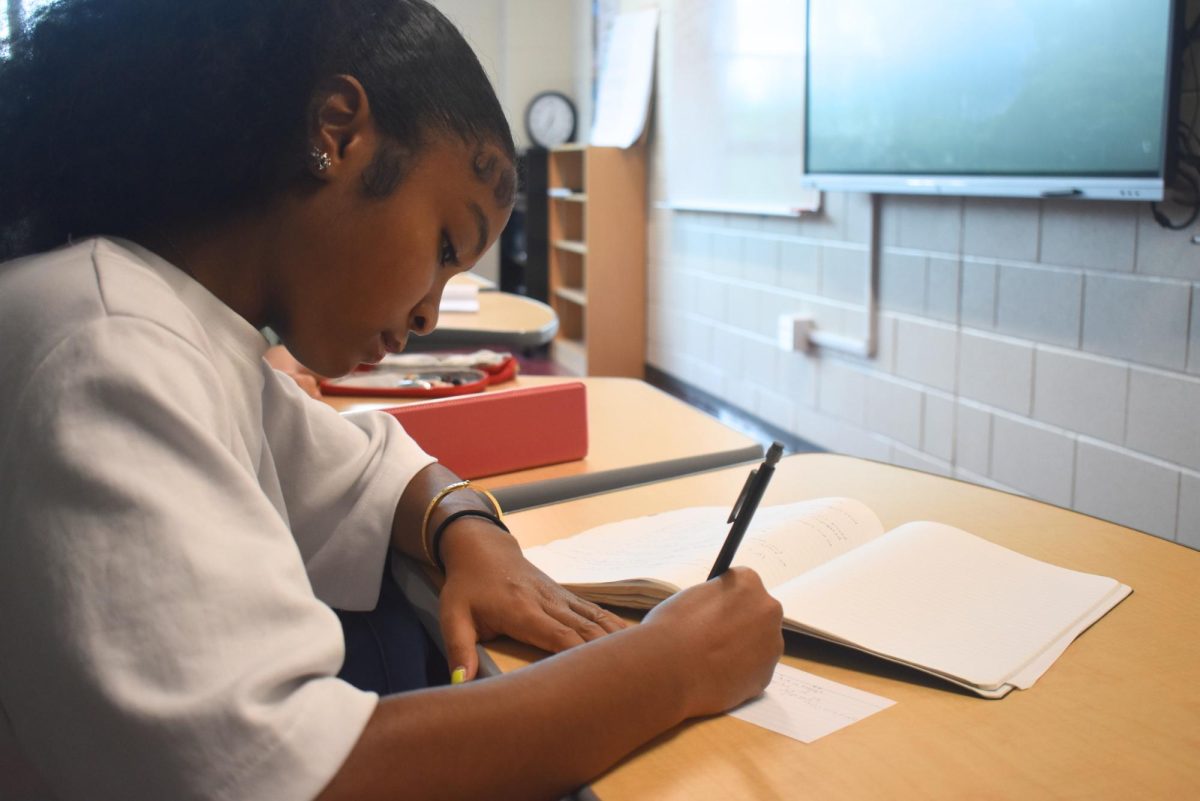

The Midtown administration implemented a new universal grading system this school year, raising debate among students and teachers.

The new system impacts many grading aspects, including late grade policies and the summative-formative weight distribution, while also creating a grading floor. Social Studies teacher James Sullivan said the purpose of these changes are to make opportunities for students more equitable.

“There had been discussion over at least the last year about needing to do something to make sure that grades were a little fairer to students and teachers because there was a lot of variation in how teachers graded students,” Sullivan said. “We were looking for something that all teachers could understand a bit more, plus something that might give a little bit more fairness.”

While teachers held more autonomy in the past to devise their own grading systems, the new system now applies to all classes, ending the majority of variations.

“It is an issue of equity,” Spanish teacher Liliana Ortegon said. “We are just trying to level the field for all of the students, so you’ll have the same opportunities, regardless of the class that you’re taking. In the past, [grading systems] were maybe different for every subject or [even] different within the same subject.”

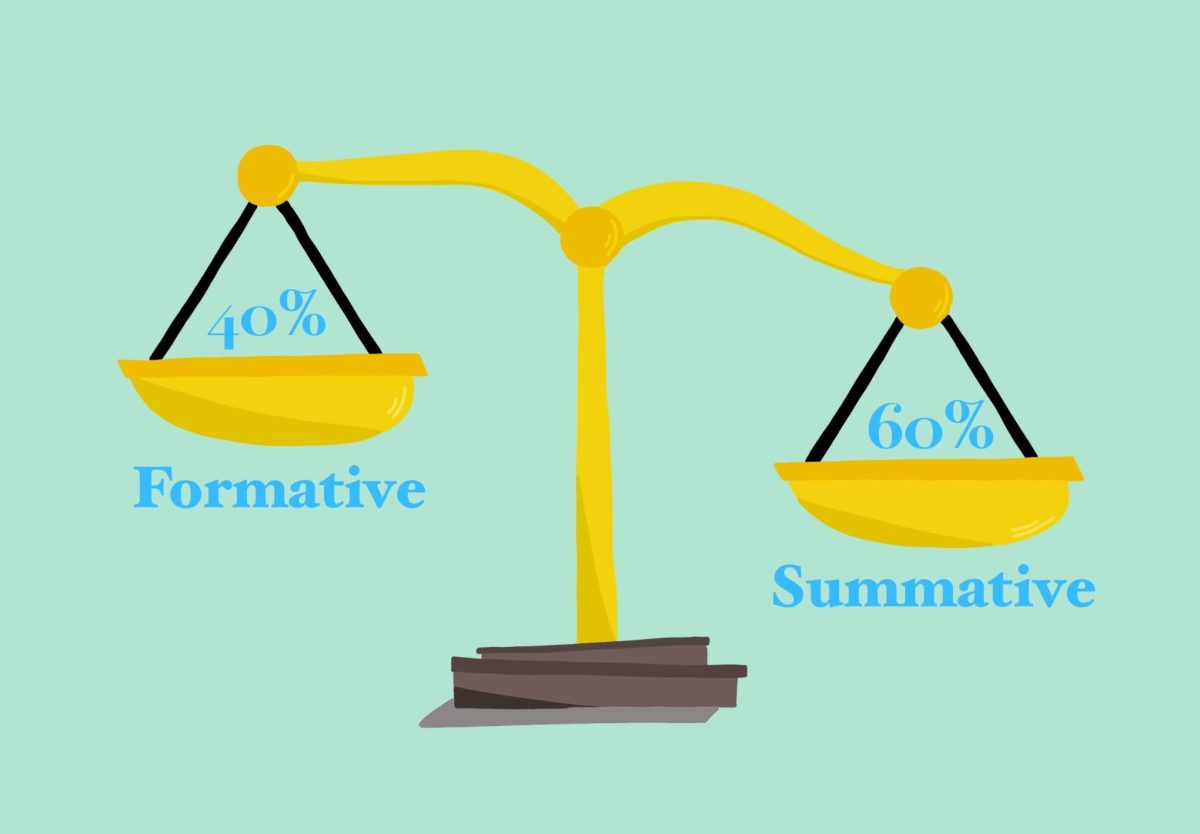

Under the new grading policy, all classes will have 60% summative and 40% formative categories. Literature teacher Kate Carter believes that having a universal two-category system is beneficial for the school.

“I think that we’ve made some solid improvements,” Carter said. “Specifically, I think having two categories across the board that are very transparent about what the building blocks are towards skills and standards, and then what the actual summative assessments that show us how we have mastered what we are learning, is really positive movement”

The new grade distribution is meant to better reflect students’ comprehension and applications of what they are learning.

“I think it’s a major improvement toward the reflection of student knowledge,” Carter said.

“In the past, students can [get away with] turning in work that they may or may not have even done themselves, and then they never actually get what they’re doing. But in this sense, when the summative [category] is 60%, you can’t [avoid it].”

However, sophomore Harper Green believes the weight placed on the summative category does not accurately reflect what a student may know or not.

“I think that for people who have anxiety and don’t perform well under pressure, it’s more difficult when the majority of your grade relies on tests,” Green said. “I think, in some ways, it is a fair way of grading students, especially people who don’t have time to do homework, but if you’re a bad test taker, then it’s not exactly fair.”

Ortegon believes a high summative percentage doesn’t completely reflect a student’s knowledge as different subjects require different grading standards.

“During the formative assessments, we see more performance than what we do during the summative assessment because it is a language class,” Ortegon said. “Sometimes, [the new percent distribution] is not an accurate reflection if the assessment doesn’t include all of the skills that we measure. It might include reading, writing, speaking and listening, and I’m measuring all of that in one assessment.”

Alongside the change to percent distributions, AP classes now have a 20% penalty for work turned in late.

“I love that there’s a little bit more rigor and expectations for the AP classes, [considering] that they are given an extra 10 points just because they’re enrolled in that class,” Carter said. “Also, it’s a college-level course and at most colleges, professors don’t permit students to turn in work late; so, I do think it’s absolutely appropriate.”

On the other hand, on-level and honors classes have no penalty for late assignments. Teacher Lisa Sparkfield* believes this will have a negative effect on students.

“I think not allowing students to be held accountable for their workload is going to damage them, especially if they’re college-bound, where there are not only late penalties in college, but you also can’t even turn in the work after a due date,” Williams* said. “It’s not preparing Midtown students at all.”

Another factor as part of the new system is the newly implemented grading floor, which makes 50% the lowest grade a student can receive, including on missing assignments.

“I’m happy with it because if someone doesn’t do the work, a 50% is still a failing grade, but it’s not as hard to come back from [than a 0],” Sullivan said. “If you get a few zeros, that’s very hard to come back. Raising the floor a little bit will make it easier to do some work for a passing grade.”

While some students and teachers may find the grading floor beneficial, others question whether it is a fair system.

“I don’t think it’s great, especially if someone doesn’t turn in an assignment [and] still gets the same score as someone that tries pretty hard and gets a 50%; that’s pretty unfair,” sophomore Jamie Drake said.”

Sparkfield said it is unfair for a person to receive a 50%.

“It doesn’t really make sense if a student receives a raw score of a 30% on a quiz, and I have to manually change it to a 50%, and it’s still the same grade as someone who didn’t take the quiz at all,” Sparkfield said. “Logically, that just doesn’t make a lot of sense to me.”

The new grading floor policy prompts some teachers to wonder whether students will be motivated to complete their work, or whether they may become discouraged from participating in classwork.

“If students start to realize, ‘This doesn’t count’ or ‘This doesn’t matter,’ I’m afraid I’m going to see effort go down a little bit,” literature teacher Najla Phillips said.

To retake tests, however, students will need to complete all missing assignments.Test retakes are mandatory for anyone who received below a 69% and optional for those who received above a 70%.

“Now, everyone’s allowed to retest, which I think is great,” Sparkfield said. “Also, now, you can’t re-test unless you finish all the formatives or missings for that unit. So, that’s going to make students sit down and actually do the work and learn, and that’s what every single teacher wants.”

Despite the numerous debates regarding the new grading system regulations, many students and teachers remain optimistic that it will work well in the future.

“I say that I am hopeful; I want this to work for the students, and I want this to work for the teachers because I know that is a huge change for us,” Ortegon said. “I hope that this will be a positive change. I hope that the students take ownership of the grades and performance and do well.”

*Lisa Sparkfield is a pseudonym to protect the identity of a Midtown teacher.