Imagine a world where getting into college solely depends on your abilities, regardless of your background and everyone is provided equal resources and treatment to ensure admission to elite colleges is reserved for those who truly deserve it.

That’s the future that the Supreme Court aimed to create with their recent decision to strike down the use of race-based admissions policies in colleges and universities. However, in the real world, this utopian pursuit faces significant challenges and getting into a prestigious institution can be overwhelming, unrealistic and not the best decision for everyone.

America presents a conundrum. We pride ourselves on being a ‘melting pot’, a diverse landscape in which we use our differing perspectives and backgrounds to better educate ourselves. Striving for racial diversity in college admissions, however, inadvertently ends up only favoring the privileged. Creating a racially diverse campus using race-based admissions practices also tends to create a socioeconomically uniform one, as people with more resources are significantly more likely to succeed in college admissions.

The whole question is paradoxical: how do we create a diverse (in every meaning of the word, race, class, gender and so much more) educational landscape, while judging people on information, like essays, standardized test scores and grades, that naturally disfavors diversity? My answer — we can’t. Rather than endlessly trying to fix the admissions process, perhaps we should redirect our efforts towards repairing what comes after: the job market and more specifically, the American attitude towards college prestige.

When searching for a career after graduating, a college degree, especially from a highly ranked college, is in some fields a golden ticket, or at least the start to a successful career. But if the prestige behind a college is determined by an admissions process that we already know to be arbitrary and elitist, is the degree itself also arbitrary and elitist?

When the go-to way to measure prestige, The US News and World Report ranking, is widely regarded by researchers as a load of nothing, is the only value gained from going to an elite school the established connections and idea of prestige you get upon graduation?

Prestige, despite being fabricated, plays a crucial role in the job market, whether we like it or not. Candidates from renowned schools are often assumed to be more hardworking and more intelligent than those from less-prestigious and state schools. But where does that leave those who attend schools that fall somewhere between Ivy League and state universities?

These institutions demand hefty tuition fees, yet they don’t necessarily offer the same level of advantage in the job market. Georgia is a specifically interesting case to study in this discussion, as two of the state schools, The University of Georgia and Georgia Tech, are both prestigious and offered to residents at a low cost. This brings up an important question: Is there any tangible advantage for students from Georgia to attend schools ranked higher than Tech and UGA but not quite Ivy League caliber?

Each candidate must decide for themselves, but need to be conscious of whether they’re getting as many benefits out of the institutions as possible.

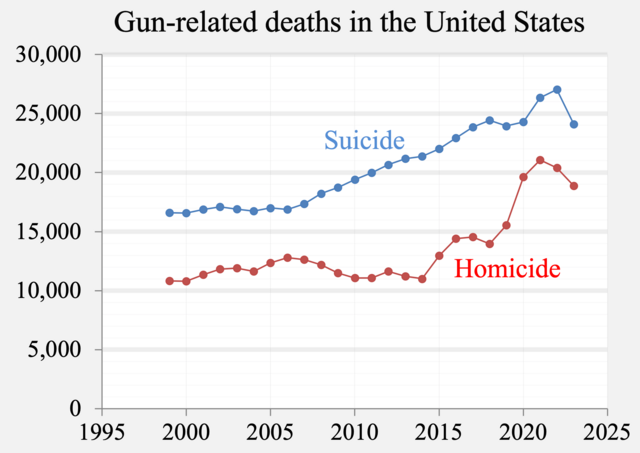

After college, according to a survey done by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 29% of workers report as ‘not using their degree in daily work’, and only 20% of job listings are exclusive for people with Bachelor’s degrees. Student loan debt has tripled since 2006 and now makes up $1.45 trillion in household debt, according to Federal Reserve Bank data.

If growth continues at this rate, student loan balances are set to overtake those of mortgages by 2042. College is getting increasingly more expensive, less people are using their degrees and having a degree is becoming less and less valued. American values must shift; the value of prestige in higher education should be significantly reduced and more high schoolers should consider options like apprenticeship, trade school and getting an associates degree.