Prison conditions raise concern among people impacted by Georgia criminal system, advocates

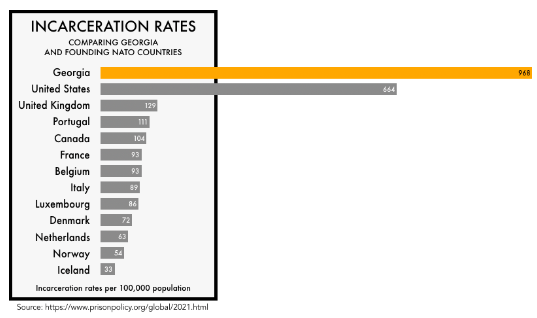

According to the World Population Review, Georgia has the 4th highest incarceration rate in the United States. For every 100,000 people, 968 people are incarcerated in Georgia, according to the Prison Policy Initiative.

May 22, 2023

In recent years, family members of incarcerated people and activists relay accounts of rising violence in prisons and lack of medical care, sparking concerns of neglectful conditions in Georgia’s prisons.

In a hearing convened by the Georgia House Democratic Caucus Committee on Crisis in Prisons in September of 2021, Jennifer Bradley said that her son, Carrington “Sip” Frye, was stabbed to death while serving time in the Macon State Prison in March of 2020.

“There has been a grave injustice done to me and my family by the Georgia Department of Corrections,” Bradley said during the hearing. “Me and my son were so insignificant to them, prison officials never picked up the call to notify me of Sip’s death. It wasn’t until hours later that I received notification from another prisoner. To date, I’ve never received any of my son’s belongings.”

One week prior to the hearing, the Department of Justice began a federal investigation of the Georgia Department of Corrections that remains ongoing.

The Georgia Department of Corrections did not respond to a request for comment.

A recent project at the University of California, Los Angeles reported a 46% increase in overall prison mortality rates across the United States in 2020. The project also documented that 6,182 deaths in 2020 compared to 4,240 deaths in 2019, even though the overall U.S. prison population dropped by 10%.

Motherhood Beyond Bars, a non-profit organization with a mission to reunite incarcerated mothers with their children and permanently end cycles of incarceration in families, has spoken on increasing mortality rates and violence within prisons. Amy Ard, a Midtown parent and executive director of Motherhood Beyond Bars, said that the increase in violence in prisons is a result of severe understaffing, creating a lack of security.

“Things are spinning out of control inside the prisons,” Ard said. “[Working in prisons is] really hard, and it’s not a safe place to work. Because it’s so violent inside [prisons] right now; it doesn’t attract a lot of people who might otherwise want to work there and might be willing to work there for a pretty low salary.”

The Southern Center for Human Rights, a non-profit public interest law firm working to bring about dignity and justice for people incarcerated in the South, has advocated for people in prison impacted by understaffing.

Page Dukes, a communications associate for the Southern Center for Human Rights said low rates of staffing in prisons have caused limited medical access for incarcerated people.

“We found that there were prisons that were operating with 30% of the required staff,” Dukes said. “When there’s not enough staff, then people aren’t able to have access to medical care, to mental health care, to basic things like showers, and food and legal services. So, to say that it’s a crisis in Georgia for them is really an understatement at this point.”

High rates of incarceration in Georgia have exacerbated poor prison conditions, according to Dukes, who spent 10 years in prison.

“Georgia has the highest rate of correctional control in the world, so we have more people serving long-sentences of parole and probation,” Dukes said. “We also have a very high rate of people incarcerated. People are serving really, really long sentences, and over the years with inadequate health care, things that would be easily treatable become deadly.”

Ard said medical support is particularly sparse for pregnant women in Georgia prisons. According to Ard, women in prison are given 48 hours in the hospital after giving birth before they go back to prison, and they are not given screening for postpartum depression or breastfeeding support.

“We want to be looking at programs for women in the prison system where they could stay with their babies and get the mental health and substance help that they need,” Ard said. “We also know that separating moms and babies at that time in a child’s life sets that child up for failure, too.”

Dukes says action is often not prioritized because of the stigma surrounding the idea that those convicted of crimes are more deserving of poor conditions.

“Whatever landed them in prison, whether they were guilty or not, it’s not okay to strip people of their humanity and subject them to brutality and neglect,” Dukes said.

Dukes says the most reasonable way to combat the violence and inadequate medical access present in Georgia prisons is to decarcerate prisons.

“… because we have relied on mass incarceration for so long that now we have huge populations of people aging in prison whom we can’t take care of; we can’t protect people in those kinds of environments.”

Ard sees a future of change in Georgia prison conditions as the Georgia Department of Corrections is being investigated and a new Department of Justice commissioner, Tyrone Oliver, has been hired.

“It is one of my most fervent prayers today that out of Sip’s blood and out of my family’s devastation and pain, come a new and improved system that will turn Georgia’s Department of Corrections from places of retribution into place of true rehabilitation and restoration,” Bradley said.