[slideshow_deploy id=’9533′]

The first time I ever saw Brannu Fulton was three years ago, trotting down the middle of the road on a big brown horse at 4 a.m. Last week I drove down Howell Mill Road, the away from the lights of Buckhead and into the neighborhood’s grittier area took a right on Bowen Street and though unfamiliar with the area, the two women on horseback finishing up their ride were a sure sign that I’m in the right place.

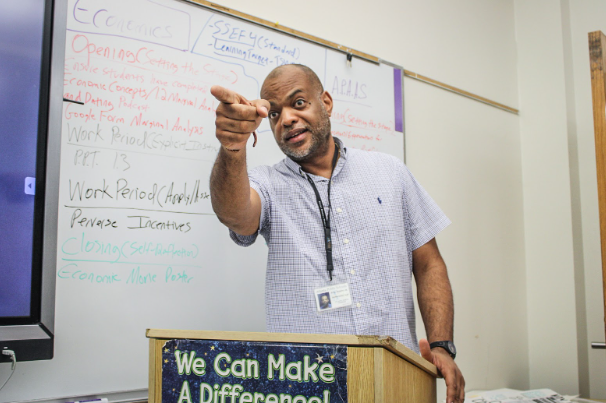

I park my car and find Brannu Fulton, the man that has come to be known as the Urban Cowboy. It’s a title that could be given out lightly by local news stations, but Fulton owns it. Fulton is a good looking, black, 20-something with a staccato giggle and a near superhuman ability to talk fast and frequently. If you Google Fulton, older pictures show him adorned in a Polo sweater and a gold chain. But at this point in time, Brannu Fulton is (to borrow his favorite phrase) “cowboyin’ out.” Adorned in a tasseled, brown leather jacket and of course, the boots, Fulton shakes my hand, immediately leads me to the “fields” and begins explaining his vision.

“We’re just ridin’ around the city until we get this place situated,” said Fulton, kicking at the sand we stand in. Fulton’s ranch consists of a wooden cabin and a few hundred feet of sand, sporadically divided by a few wooden fences and posts. To our left, the lights of someone’s home glow down on four horses eating hay and pawing at the dirt.

“This place is going to be riding for veterans and for kids,” said Fulton, “like therapeutic riding. But my therapeutic riding isn’t going to be the typical therapeutic riding. When I think about therapeutic I just think of you talking to a friend, if you’re feeling down or hurt. I want my horses and this place to be therapeutic because it puts a good feeling in your heart.”

Every horse at Fulton’s ranch is bought wild. “That’s how I get them at a low price, they’ve never been ridden before,” he said. Though my knowledge of horses and their training is limited to Disney movies and a few quick Internet searches, even I know that “breaking” a stallion is tough. But Fulton has had years of experience.

Fulton grew up in Brooklyn, NY where his grandfather introduced him to horses at a young age. His grandfather was a member of the Federation of Black Cowboys, who, according to Fulton were “mostly old older guys and they used to ride the horses all through the neighborhoods, like in the projects and everything.”

For the sake of him learning in a more conventional setting, Fulton’s grandfather brought him to the elite Jamaica Bay Riding Club. Frequently the only black kid there, (“Jamaica Bay. I didn’t have no friends there!”) Fulton aims for his ranch to be different.

“I want there to be a spot where I can take kids from that side of Atlanta,” he says pointing to the bright lights of Buckhead, “and the kids that live in the Bluff, Boulevard, where they can easily come together. So it’s like two kids with two different backgrounds but making them understand how to be friendly and appreciate everybody and use the horse to make them a team.”

Fulton says all this while scanning his property, a twinkle in his eye. Though not much to look at, I can tell that this plot of land is a literal symbol of Fulton’s dream. A dream that hasn’t come without sacrifice.

“I’ve spent a lot of time with these things, I’ve lost some pretty girlfriends. People see me and they’re like ‘oh you got it made’ but they don’t know the sacrifice. Like I’m thuggin it out! I’m stayin’ right here tonight. No heat! No nothin’! It’s cold!”

I’m led inside the wooden cabin and I do concur, it is cold. There’s nothing in the cabin but a queen sized bed stacked tall with blankets and a large pile of clothing much too small to belong to the Urban Cowboy. “These are clothes that people have donated. So say I ride Tuesday, I come in here, get a couple and I just ride around and give this to a kid.”

As much Robin Hood (but without the stealing) as he is Roy Rogers.

My only prior experience with horses was on family vacation in Tennessee. For my sister’s birthday, we found a ranch where we could ride obese ponies along some trails at a pace so slow, we might as well have walked. The rancher explained that the horses were so domesticated, they were no longer capable of any speed other than 2 miles per hour. When I ask Fulton if his horses are in the same condition, he smiles as if accepting the challenge. “Oh no no, they can go. Let’s go on a ride,” he says.

I’m given an equestrian crash course as the cowboy saddles my steed named Opera. I jokingly ask if he’s ever taken Opera to Club Opera. “Yeah yeah I’ve been trying to work something out with them,” he says, “but I haven’t met the owner yet.”

We trot down Howell Mill Road, past auto shops where every car window is smashed in and industrial parks gated off for the night, until we reach the waterworks. I’m so distracted by the skyline’s reflection on the lake that I almost steer my horse right into the road. Despite my near accident, Fulton was right. It was about as therapeutic as it gets. I couldn’t stop smiling. There was just something special about doing something people have been doing for thousands of years, in a place where it’s never been done before. And though Brannu kept talking at his feverish pace while riding 10 or so feet in front of me, I was only able to pick out one thing he said.

“I’m redefining cowboy. It’s bigger than having a horse, or wearing boots and a hat. It’s about your growth and your patience and your heart and your spirit, because that’s all a horse needs.”