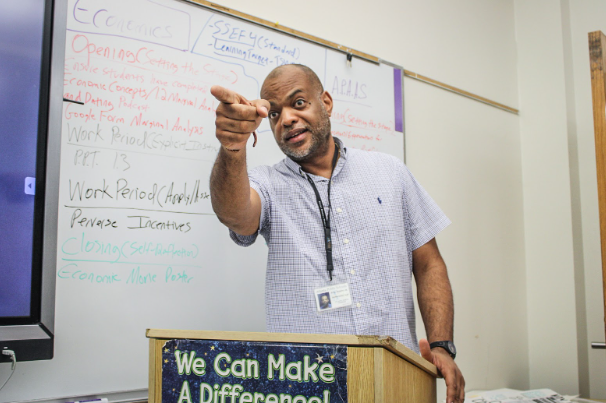

Photo Courtesy of Kent D. Johnson/ Atlanta Journal Constitution

Since the APS cheating scandal broke in 2009, it has been featured in major news outlets in Atlanta and across the United States. The judge presiding over the case has ties to APS; he is a Grady alumnus.

Jerry Baxter, whose father was a Grady disciplinarian and later the principal of Roosevelt High School, was the third and last child in his family to attend Grady. Baxter said that by the time he got to Grady, there were high expectations for him because one of his older brothers was a star athlete and the other an outstanding student.

Baxter’s time at Grady, 1962-1967, was marked by complications after the integration of public schools.

“When I went to Grady, they were just beginning to get black students, and there were only eight or 10 and they were all hand-picked,” Baxter said. “And then they integrated the athletics. Before, the black schools played the black schools and the white schools played the white schools. When I got there, they combined the two leagues and we got beat really bad.”

Baxter said that while he attended Grady, the focus was much more on sports than academic extracurriculars. Baxter played right tackle on the football team in addition to golf, baseball and basketball.

“I was pretty tall so I moved people out of the way to get rebounds, but I got fouled out nearly every game,” Baxter said. “I averaged more fouls than I did points.”

Baxter and one of his childhood friends, Alan Begner, met while in eighth grade at Grady, then the first grade at Grady.

“[Baxter] was the most popular person in our class,” Begner said. “He was an excellent athlete [and] … also a good student.”

After graduating from Grady in 1967 and majoring in business at the University of Georgia, Baxter applied to the law school at UGA. He said he applied because he was inspired by his brothers, one of whom is a lawyer and the other a doctor.

“Some people plan what they are going to be their whole lives,” Baxter said. “I was one of these happy-go-lucky people. I applied to UGA law and lo and behold, I got the letter that said you got accepted.”

After completing law school, Baxter landed a job in the solicitor general’s office of Fulton County, but then transferred to the district attorney’s office, where he was an assistant district attorney for 10 years. Though he was not the “star of the office,” Baxter made some friends in the courthouse who encouraged him to apply to be a judge.

“I was 35 and they said, ‘Jerry, you need to try for a judgeship,’ and I said, ‘what are you talking about. I’m 35, I don’t see that right now. I’m too young,’” Baxter said.

Nevertheless, Baxter got his name among the list of five candidates sent to the governor, who appoints a new judge when a judge dies or retires during his term. At the time, the governor of Georgia was Joe Frank Harris. Baxter was turned down the first two times, but received the judgeship from Harris for the state court of Fulton County on the third try in 1985.

“The third time the governor’s office called and said, ‘Jerry, you need to be by your phone in 10 minutes, the governor is going to call,’” Baxter said. “The governor called and said, ‘Jerry, I want you to be a judge.’ It was one of the happiest days of my life. I couldn’t believe it.”

Begner, on the other hand, said it is not a surprise to him that Baxter became a judge.

“He went the kind of route people generally do to become judges,” Begner said. “It was no surprise to me or probably anyone who knew him that he ended up a judge.”

Despite the achievement, Baxter said that he was very nervous the first time he presided over a case because it was a civil suit and not the criminal trials he was used to.

“I was scared to death,” Baxter said. “You become a judge, and they give you a robe, and you go into court and everyone stands up and people do what you say.”

Since that trial 28 years ago, Baxter has melded into his role as a judge. According to Baxter, however, the APS cheating case has been his most difficult trial yet.

“It was quite a shock when I got the news because nobody ever had a case like this; 35 defendants,” Baxter said. “I sort of freaked out, but then I got thinking that I had to handle this and handle it like my other business. I’m just taking it one day at a time. It’s like the biggest challenge in my professional life is trying to shepherd this case through the system.”

Baxter started out by telling the defendants that they had to have separate lawyers to avoid conflicts of interest, but has found it difficult to find a jury for each of this case since it would involve people taking off work for around six months.

Though a Grady alumnus, Baxter said he will not let his past influence his thoughts about the trials.

“I can give everyone that wants a trial a fair trial and not interject my thoughts or anything,” Baxter said. “You can’t just flush your head out of everything of what you’ve seen or heard but as far as being fair and giving them a fair trial, I can do that.”

Begner also thinks that Baxter will be able to keep his opinions out of the trial.

“I think that everyone will find out about him that he is a moderate judge but he has a deep sense of fundamental fairness,” Begner said. “He is evenhanded in the way he treats defendants and prosecutors.”

Despite the bad light that has been shed on APS, Baxter sees a positive spin for the school system.

“APS has a great opportunity now with all the changes being made [and] with new and young ideas being brought in that hopefully the Atlanta school system will leave that image and create a better school system where all children … get a good education,” Baxter said.