Comedy isn’t an excuse for offensive humor

Comedian Dave Chappelle’s “The Closer” (2021) standup show has sparked criticism, citing transphobic comments made by Chappelle.

November 29, 2021

Some jokes aren’t funny. It goes beyond an ill-fated meme on Twitter or a poorly executed SNL sketch. It’s when the facade of humor is used to cover up inherent bias and prejudices, masquerading behind the thin veil of “comedy.”

Take comedian Dave Chappelle’s Netflix special, “The Closer.” Chappelle has recently come under fire for transphobic jokes cracked in his special. For example, he praised author J.K. Rowling, cited as making transphobic comments in the past, and proclaimed that he is “Team Terf.” The derogatory acronym stands for a “trans-exclusionary radical feminist,” and used by feminists who don’t accept transgender women as part of the community. Chappelle is a highly successful comedian, and undeniably has vast amounts of influence and power in the comedy field. This is exemplified by his five Emmy Awards, three Grammy Awards and six Netflix specials. However, what Chappelle does with the power he holds is the root of the problem.

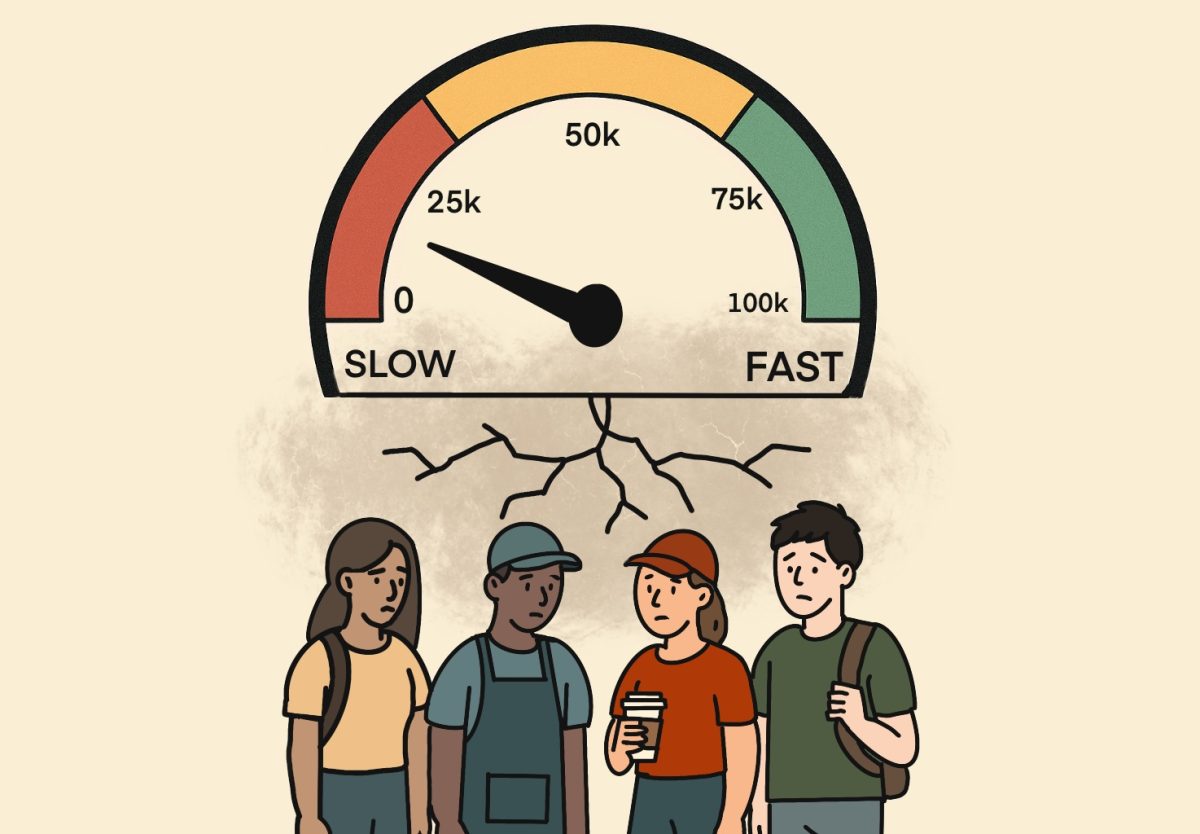

As an influential comedian with a large audience, Chappelle is directly targeting the transgender community. An already vulnerable community, transgender people are constantly marginalized in today’s society. Making them the bunt of his punchline creates an unfair power dynamic. Chapelle, “punching down” on a marginalized group, normalizes and reinforces the inherent biases of the audience.

The transgender community doesn’t stand alone. Countless other marginalized groups in society have found themselves victims of comedians blurring the lines between humor and straight arrogance.

In 2019, SNL fired comedian Shane Gillis, who was let go due to problematic comments he made in the past. In particular, Gillis used a racial slur and mocked Chinese accents, directly targeting Asian Americans. In addition to Gillis’ firing, SNL also hired Bowen Yang, their first Asian-American cast member. Bowen’s historic hiring adds to the multifaceted situation, as preaching diversity and inclusion has no impact when the actions of an oppressor overshadow the oppressed. When addressing the controversy, Gillis proclaimed the anti-Asian sentiments he spewed were “just a joke.”

The “just a joke” defense, used by Gillis and countless other comedians, invalidates the experience of the marginalized. This type of behavior reinforces the “othering” of minorities, by emphasizing outsider status and cultural differences. From a personal standpoint, it’s isolating. As an Asian American, having Gillis, the “invincible,” invalidate the cries of racism from the marginalized is unacceptable. Humor that hides under a mask of any sort of prejudice is abhorrent, and it only further blurs the lines between comedy and bigotry.

However, comedy can also be used as a tool for change. It can take a powerful form, using tactics to connect audiences through difficult topics, instead of isolating. Take comedian Hasan Minhaj’s Netflix special “Homecoming King,” in which he retells the story of his prom date and how his date’s mother didn’t approve of him “because he was brown.” While Minhaj walks through a tough topic, he utilizes storytelling and humor to shine a light on a broader picture regarding race relations in America. Humor can be used to connect audiences through the lens of personal experience and to create a sense of human connection, which can help audience members recognize racism in a way they haven’t thought of before.

Comedians have the opportunity to influence public discourse and overcome personal bias, not just entertain. Laughter is the best medicine — especially when used to heal the wounds of racism and bigotry, through the shared human experience.