[slideshow_deploy id=’8771′]

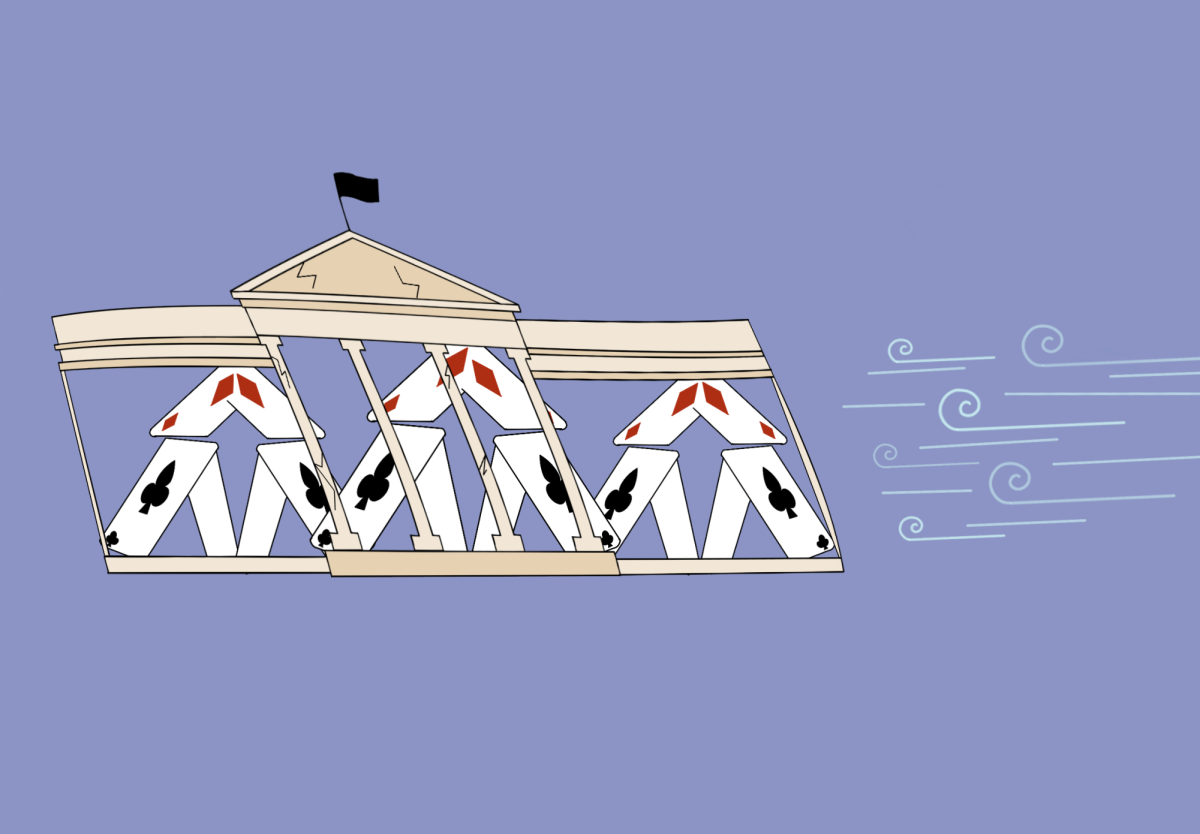

Atlanta Public Schools’ charter schools cleared a major financial hurdle on Sept. 24 when Georgia’s Supreme Court ruled that they don’t have to help the district pay off its pension obligations. The decision is a setback for Superintendent Erroll Davis and the district, which had appealed the case after Fulton County Superior Court Judge Wendy Shoob ruled last December in favor of charter schools.

Atlanta Public Schools’ charter schools cleared a major financial hurdle on Sept. 24 when Georgia’s Supreme Court ruled that they don’t have to help the district pay off its pension obligations. The decision is a setback for Superintendent Erroll Davis and the district, which had appealed the case after Fulton County Superior Court Judge Wendy Shoob ruled last December in favor of charter schools.

The decision is another victory for charter school proponents, less than a year after Georgia voters overwhelmingly approved a constitutional amendment allowing for a state commission to review charter schools if local school boards reject them. Not everyone, however, was pleased with the ruling.

“We are disappointed in the decision because it perpetuates a funding inequity to the detriment of traditional school students,” Davis told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “Atlanta Public Schools will continue to pursue other options to resolve this growing disparity in funding for our school district.”

This disparity has been the subject of contentious argument in recent years, with both charter schools and traditional public schools

insisting that they aren’t getting their fair share of funding.

Allan Mueller, APS’s executive director of innovation, explained Davis’s position in an email.

“The Superintendent’s position is that this long-standing [pension] debt impacts all public schools in the district,” Mueller wrote, “and if charter schools do not pay their share of the liability, they will receive more funding than traditional schools receive, creating a disparity that is not only untenable and unsustainable, but is neither in the spirit nor the letter of the law, which seeks to create an equitable funding model.”

Kelly Cadman, the vice president of school services for the Georgia Charter Schools Association, disagrees. Cadman argued that charter schools’ debt can’t get transferred to the district, so the district’s debt shouldn’t be transferred to charter schools.

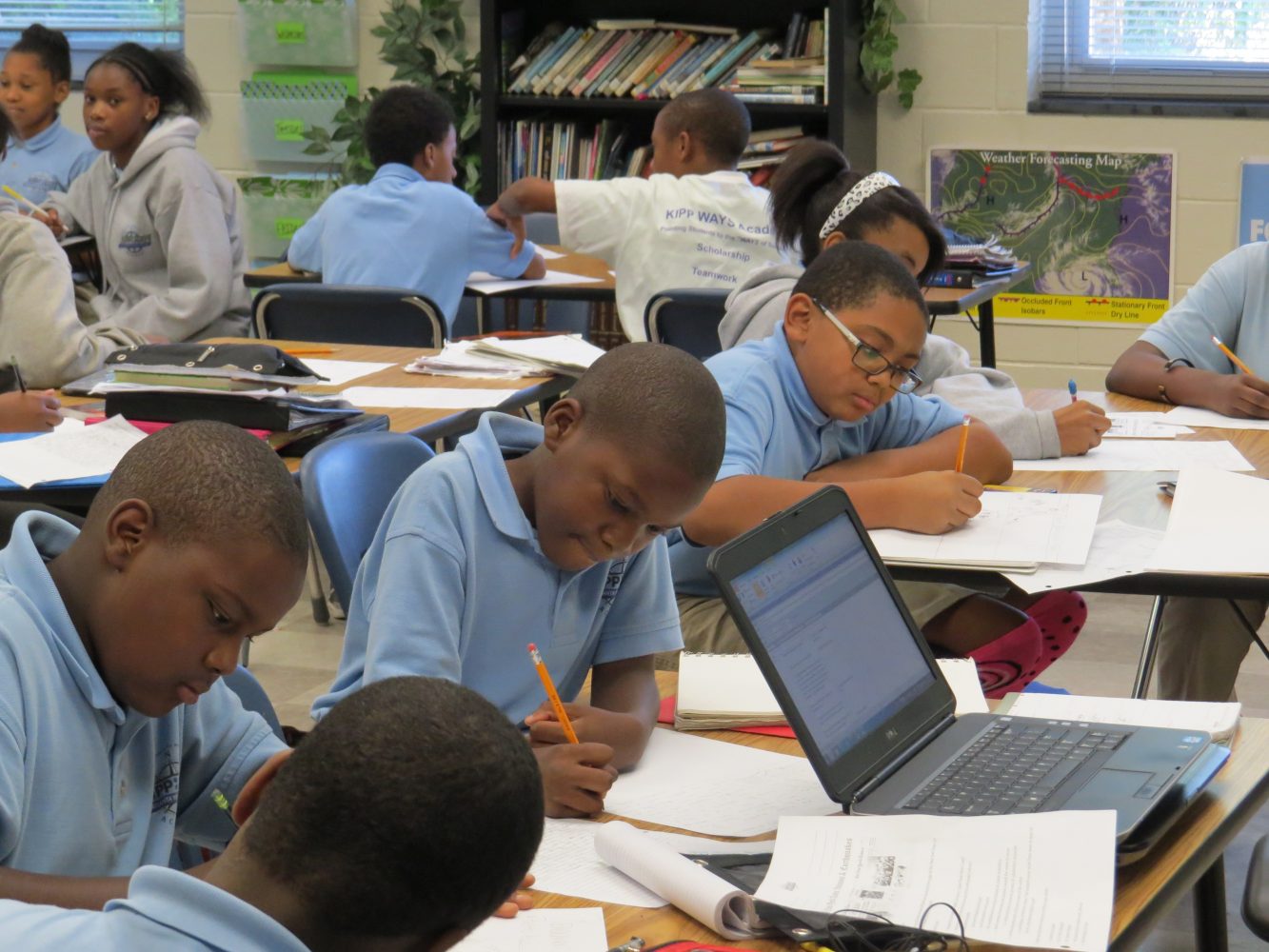

David Jernigan, the executive director of the Atlanta branch of KIPP, a national network of charter schools, believes that charter schools shouldn’t be asked to assume debt they did not have a hand in creating.

“Charter schools that were not around when this pension liability was created should not be expected to pay into that liability,” Jernigan said.

Mueller, however, insisted that it is unfair to force only traditional schools to help pay off APS’s pension obligations.

“While some might argue that it is unfair to ask all public schools in the district to pay this old debt, it is even less fair to ask only some schools to pay it,” Mueller wrote in the email.

APS Board Member Cecily Harsch-Kinnane, who represents Grady’s district, agrees, arguing that as more and more students transfer to charter schools that don’t have to help pay off the pension liabilities, traditional schools will have to pay more.

“The students left [in traditional public schools] will be paying a bigger and bigger price,” Harsch-Kinnane said.

Jernigan, however, argued that charter schools actually receive less per-student funding than traditional public schools.

“It’s been suggested in this whole Supreme Court case that somehow charter schools are getting more than APS traditional public school students, and that’s not the reality,” Jernigan said.

Robert Stockwell, who analyzes APS finances on his blog Financial Deconstruction, said, under the current budget, APS spends almost $4,000 more per student on traditional public schools than it spends on charter schools.

Jarod Apperson, however, who analyzes metro Atlanta education data, pointed out several reasons why this funding gap doesn’t reflect any inequity. First of all, Apperson argued, since the traditional public schools in APS have been around longer, they have accumulated a reserve fund to be spent during economic downturns. The reason APS spending on traditional public schools is higher, Apperson argued, is in part because the traditional schools are able to spend their reserve funds while the charter schools are too new to have reserve funds.

“The fact that the traditional schools saved some in the past, and they’re now spending it, that isn’t creating something unfair, necessarily,” Apperson said.

Apperson said another reason for the difference in funding is that the formula mandated by the Georgia Department of Education for how much funding traditional schools and charter schools receive depends on student characteristics that vary between the two types of schools. Mueller echoed this point.

“The funding a school receives may differ depending on the characteristics of the population they serve,” Mueller wrote in an email. “A charter school serving fewer children with special needs, or fewer gifted students, for example, may receive less per-pupil funding than a traditional school with similar enrollment numbers.”

Another factor—the experience of the faculty—further skews the comparison in favor of charter schools. Because charter schools are more likely to have younger, less experienced teachers, Apperson said, the teachers earn less income on average than teachers at traditional schools.

“It doesn’t necessarily mean that there’s an inequity, because if [charter schools] chose to hire the staff with more years of experience and more degrees, then they would get that extra money to pay those staff the higher salary that they earn for those experience and degrees,” Apperson said.

One aspect of funding in which Apperson did recognize an inequity is SPLOST funds, which charter schools can’t access. As a result, Apperson said, charter schools have to pay for such expenses as building repairs and new furniture out of the money allotted to them by APS.

Mueller acknowledged that charter schools don’t usually receive the same amount of funding for facilities as traditional schools do, though this disparity is offset by the fact that most APS charter schools use APS facilities rent-free. Apperson also said that the fact that charter schools don’t have to help APS pay off its pension debt obligations helps counteract the effects of not receiving SPLOST funds.

“If we wanted to create something that is really fair, the charters should participate in paying off the pension, but they should also earn a portion of the SPLOST dollars to help cover repair costs,” Apperson said.

Even so, Cadman said that she has “never run across [a funding scheme] where it was to the favor of the charter school.”

“[Charter schools] are more efficient, and they buckle down, and they cut administrative costs, and they share services and they’re creative and they operate on less most of the time,” Cadman said.

Jernigan said the KIPP charter schools in Atlanta that he oversees have to do a great deal of fundraising to pay for the expenses that APS doesn’t cover.

“We lean heavily on the philanthropic community to support our efforts here in Atlanta,” Jernigan said, “and they’ve been very generous and have really supported and invested in our growth here.”