From her first day of high school to her commencement at the University of Michigan, Barbara Feinberg watched in awe as the world around her changed forever. In eight years, she witnessed the Civil Rights Movement that integrated schools across the nation transform into a nation full of young people with thoughts about movements they cared about. In Feinberg’s view, this “Revolution” all began with the March on Aug. 28, 1963; however, in the eyes of Feinberg and her fellow students at Grady High School, it was just another day with a quiz in English, maybe, or a test in math.

Although the significance of the March on Washington on the Civil Rights Movement remained to be seen at the time, Feinberg did notice the significance of the events around her. She remembered her freshman year of high school, watching the Ku Klux Klan march through downtown Atlanta in protest of the sit-ins of spring of 1960. At the time when Feinberg’s Jewish friends were stressing over their bar and bat mitzvahs, they also mentioned the Temple bombing of 1958.

“We didn’t know what it all meant,” Feinberg said.

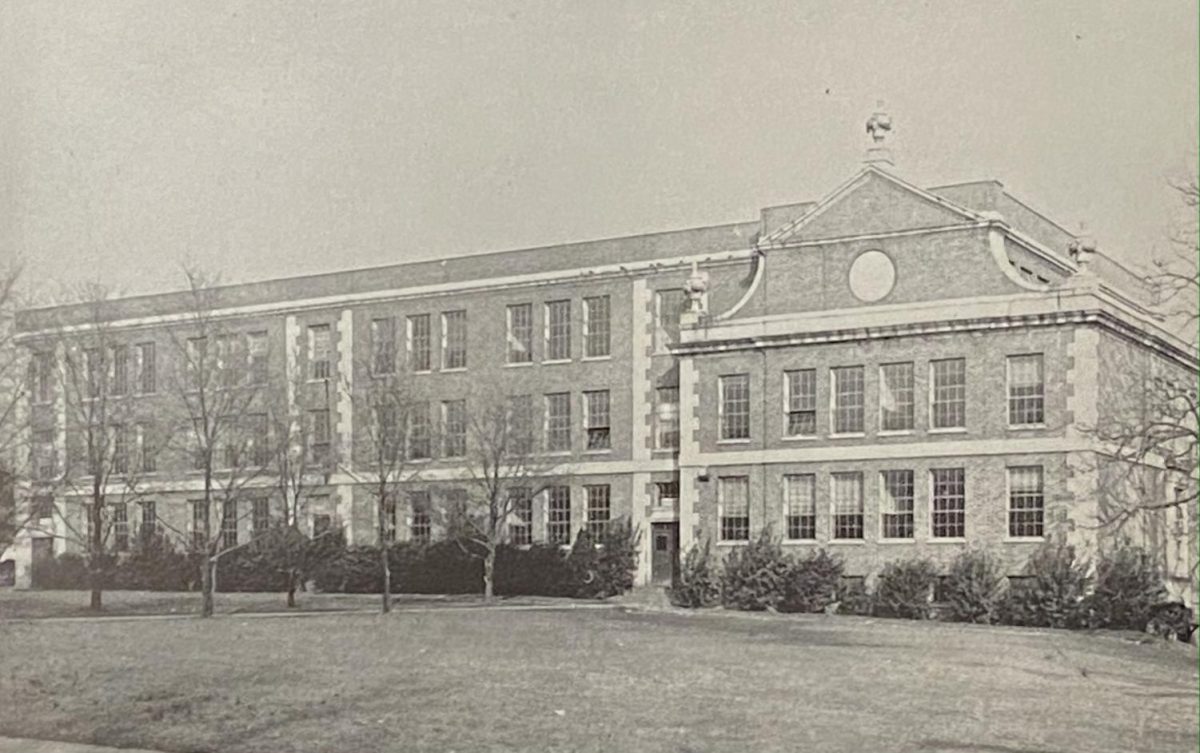

At that time, nothing seemed to be changing. Despite the official integration of Atlanta Public Schools in 1961, even the school demographics were stagnant from one decade to the next.

“There were no black students in my grade,” Feinberg said. “It was a bit of a known event.”

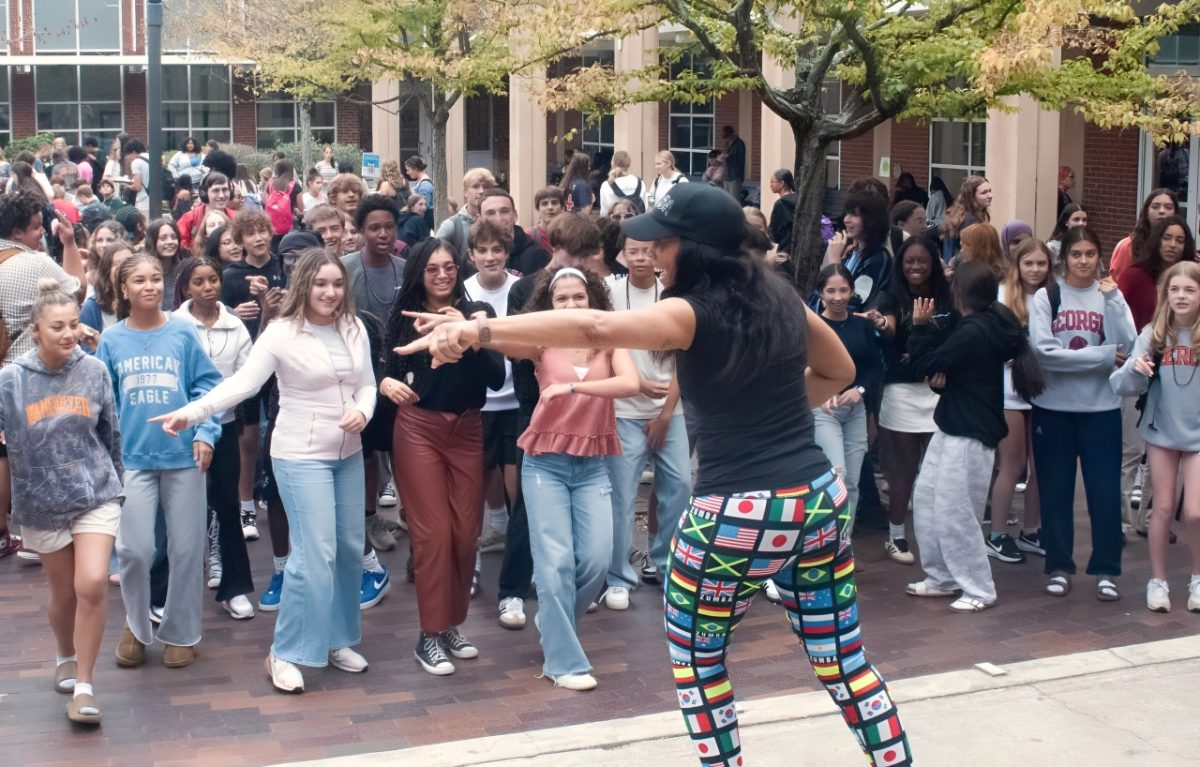

In the years between APS’ integration and the start of the Grady’s magnet program in the 1980s, more and more black students entered formally all-white schools and more and more white families moved to the suburbs or sent their children to private school.

“There was a big white flight movement,” Feinberg said.

After the start of the magnet program, which was created to draw students from across the district genuinely interested in education, many of the families that moved away in the 1960s sent their kids to APS. However, APS’ demographics are still not consistent with those of the surrounding neighborhoods.

In the 1960s, public schools were not the only public places that spirited integration policies. Across the country, civil rights legal action was happening, but most people did not seem to listen. New laws were created, but not implemented. That, according to Feinberg and other classmates like Dennis King, was why the March on Washington became so vital to the movement.

“[The March on Washington] was the beginning of the Revolution,” Feinberg said.

The civil rights leaders who attended the March on Washington also saw the power this event could have on the future. Speakers and listeners on the Mall that day relished the fact that what they were witnessing could change the world. One of those speakers was civil rights leader John Lewis, now a congressman who represents Georgia’s District 5.

In an interview with Smithsonian Magazine, Lewis mentioned that his job was to write a speech for the underground leaders of the movement: young people. Lewis was instructed to motivate the thousands of 20-somethings who were planning to attend the March on Washington into action.

“We cannot support the administration’s proposed civil rights bill,” Lewis said in Smithsonian Magazine. “It was too little, too late. It did not protect old women and young children in nonviolent protests run down by policemen on horseback and police dogs.”

Lewis later stated in the interview that these quotes were eventually taken out of his speech; nonetheless, the idea that people’s views would only change with radical action still came across in his words. After that Wednesday, Aug. 28, 1963 America’s course through history was forever altered. New laws were implemented, new followers joined the movement, and a general awareness of oppression everywhere spread across the world.

But Feinberg and her friends at Grady saw the day as ordinary: homeroom in the morning, a math test before lunch and a speckle of black students walking through the sea of white in the hallway.