Living in an LGBTQ “liberal bubble”

In Atlanta, the high concentration of liberal people gives the LGBTQ community a false sense of security.

May 3, 2019

Whenever I make new friends, there’s always a time when I have to come out to them as lesbian. The first time I ever did it — seventh grade — I told all my friends at once, hoping it would be the only time I’d have to do so.

I misjudged; coming out was not a single event, but a process which I would have to repeat over and over again, whether it was to people from outside my regular social group, from extracurriculars or from summer camp. Initially, I saw coming out as a huge milestone in those friendships, like sharing an intimate secret, and I’d often get very close with people before they had any idea of my sexuality.

Over time, things have gotten much easier for me. Now, I often feel comfortable just slipping something into a conversation about being gay and then continuing on as normal. At Grady, I’ve become accustomed to feeling shielded from hate and assuming that the whole student body is as accepting of the LGBTQ community as my closest friends are. Living in the middle of Atlanta has been like living inside of a “liberal bubble” to me, where myself and many of my peers can be open about our identities without hesitation.

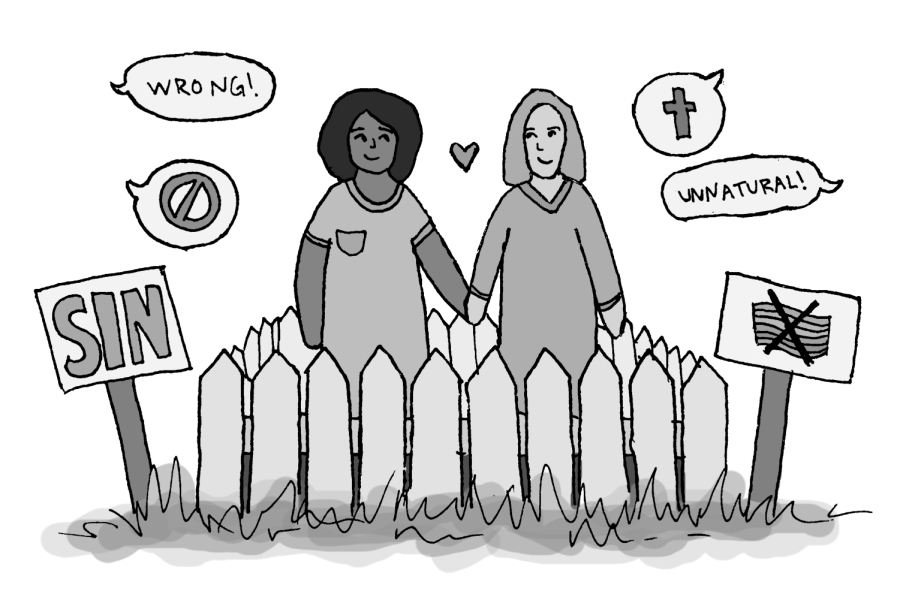

This idyllic situation, where the world is devoid of homophobia, is starkly different from reality. A 30-minute drive from Grady can take me to communities where letting strangers on about my sexuality could be dangerous. Thousands of LGBTQ people who don’t live in such tolerant neighborhoods have to keep their sexuality or gender identity a carefully-guarded secret; otherwise, they risk facing discrimination or violence.

My sexuality is easy for me to hide. I don’t dress masculine or give any other physical indication to strangers that I’m LGBTQ. That privilege is valuable; I get to determine who knows my identity and who doesn’t. However, people whose identity breaks traditional gender stereotypes have to choose between either repressing a vital part of themselves or potentially revealing their identity to anyone they meet, which opens up numerous alleys for them to be exposed to danger.

Coming out in a community that entirely rejects one’s identity takes immense audacity because LGBTQ people in those places face a heightened risk of violence. According to a New York Times analysis of FBI data, LGBTQ people face a greater risk of hate crimes than any other minority. Clearly, being open about one’s sexuality or gender identity in a resentful community presents a very real danger. Therefore, coming out is a radically different experience for people who anticipate that they’ll be accepted, like I did, versus people who might not be.

All this being said, I come from a family of progressive Democrats, and most of my friends are liberal as well. The liberal bubble I perceive is not infallible by any means; I know homophobic students and families right here at Grady, and it would be unrealistic to expect otherwise. Even in Atlanta, homophobia is still prevalent.

Nevertheless, I can’t express enough how lucky I am to live in the place I do, where I can talk openly about my sexuality and not be judged for it. Every so often, I have to remind myself not to take that for granted. This phenomenon is mostly unique to the metropolises of America, and the homophobia my LGBTQ friends and I feel so protected from will always be right around the corner. It’s important that LGBTQ people in liberal bubbles similar to mine are aware of their privilege; likewise, allies of the LGBTQ community shouldn’t underestimate how meaningful their support is, as they are instrumental to creating safe spaces like this one.