Overbearing parents create problems in school athletics

Parents who take an excessive interest in their children’s lives add pressure when it comes to school activities like sports.

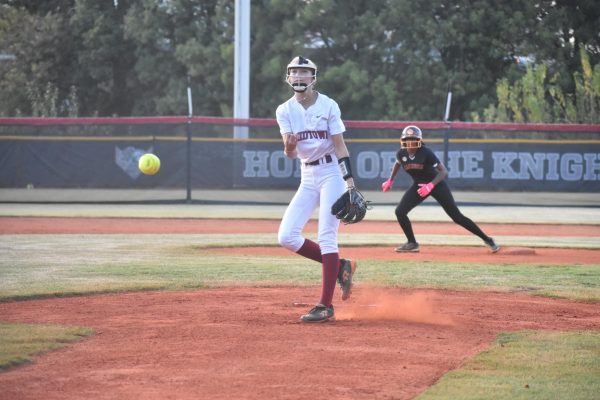

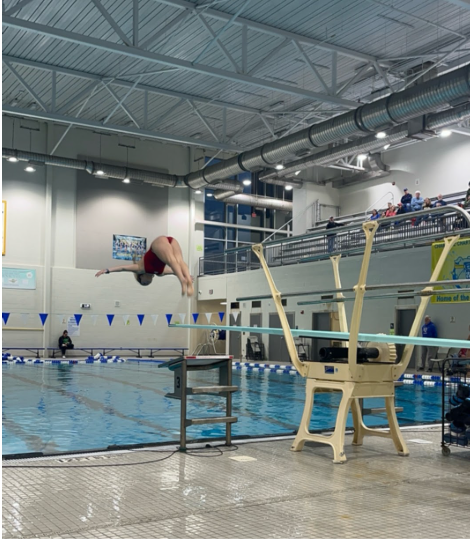

Parents: from carpooling, to washing smelly jerseys, to the loud cheering from the sidelines, find their way into almost every aspect of a child’s early athletic career.

Often, parents are the ones who choose which sport their child plays. As a child gets older, some parents have continued their controlling grip. At Grady, the issue of overbearing parents has found its way into almost every sport. This issue has resulted in the change of Atlanta Public School policy, and in some cases, caused coaches to quit.

When a parent has an issue with a coach there is a very strict set of guidelines they are supposed to follow in order to solve the problem at hand.

“The parents should speak with the coach, and if it’s not taken care of, then go to the athletic director, then from the athletic director to the assistant principal, Mr. [Rodney] Howard, who is over athletics, and then the principal,” Athletic Director John Lambert said. “At Grady, the process fails.”

Over the years, coaches have gotten progressively more frustrated with the lack of organization that the system has produced. In most situations, parents skip all of the steps and go to the last resorts. They go straight to Principal Dr. Betsy Bockman or take it one step further and go downtown to the APS headquarters.

“A lot of the times, they’ll just go to Dr. Bockman or even someone else downtown like the APS athletic director, which creates a fiasco and a negative image,” said a former coach, who chose to remain anonymous. “It has happened on a regular basis; there are a number of sports and athletic events and it has resulted in coaches saying, ‘I don’t want to be a part of this anymore.’”

The result of directly going to the APS headquarters has escalated situations that were once school-level problems into new APS policy.

“If a decision is made by someone beyond the coach, that decision becomes policy,” said an anonymous former coach. “Parents have to realize that when we make a decision about a kid, that it can affect all children.”

The participation of high school athletes outside of school competition has also skewed how parents view high school coaches.

“The culture of sports has changed a lot as student athletes have started to become specialized in sports earlier and earlier and they have multiple coaches,” health teacher and former cross country coach Tamara Aldridge said. “Parents aren’t valuing high school coaches as much as their club coaches. If their club coach says something different than the high school coach, they feel that the high school coach is wrong.”

Many of the coaches who step into these roles at the high school level do so simply for the love of the sport. The added bonus that a teacher receives for coaching is usually not much more than $2,000.

“We coach because we love coaching, it’s not about the money, because the money is a very small instrument in terms of time,” Lambert said.

When situations arise that challenge coaches unfairly, many simply feel it’s easier to step down than go through with the process of dealing with overbearing parents.

“Many times coaches feel like they are treated like second-class citizens; that’s not a good feeling,” said an anonymous former coach. “I just say ‘you know what?’ I don’t coach for the money, I coach because I care, and at certain points where I feel like you don’t really appreciate my time, I have other things I can do in my life.’”

For some athletes, this hovering parental style carries into the household.

“I have seen many examples of ‘helicopter’ parents during the cheer season at Grady,” said a cheerleader who also chose to remain anonymous. “Putting too much pressure could influence how the kid feels about the sport, and they end up not liking it as much to the point where it just feels like they do it to make the parents happy, instead of themselves.”

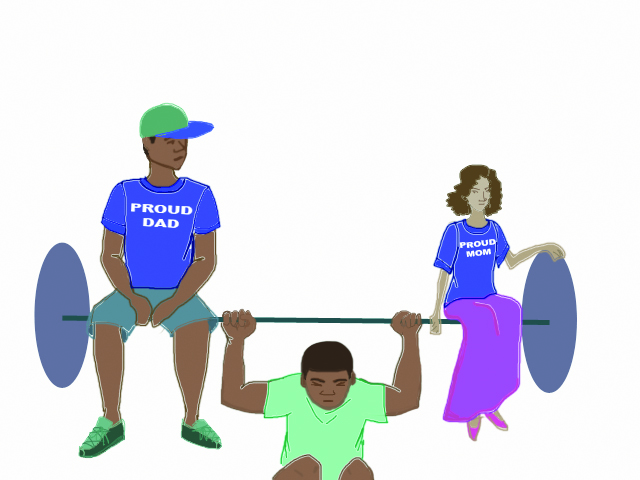

This intrusive style of parenting has taken many names. From “helicopter parents,” to “lawnmower parents,” all of them generally mean the same thing. These parents hover close to their children in many aspects, but in athletics, it is often viewed as parents trying to live vicariously through their children.

“Parents want their kids to live up to the parents’ dreams, and not the kid’s own dreams,” junior soccer player John Centner said. “They are expectant of their kids because that’s what they expected of themselves way back, but they failed to meet their goals.”

A parent’s constant hovering can have many negative effects on the child.

“It can lead to a lot of excess stress on the kid, not only do they feel the pressure from themselves to succeed, but also the pressure from their parents,” Centner said. “Pressure is not always a good thing when there’s too much.”

Many of these problems can be solved simply through the system that APS has put into place.

“I believe you can get more done if you just go to the coach first, a lot of the time, the coach does not even know the issues going on,” Lambert said. “They feel that our coaches will retaliate on the kids, which is not true.”

Anonymity was granted to sources to prevent retaliation.

Bram Mansbach is a senior and the sports section editor for the Southerner. When he is not working on pages he is across the street in Piedmont Park as...