Swim team’s difficulty retaining African American girls: hair

Hair is a barrier to attracting and keeping some promising African-American girls on swim teams.

When Simone Manuel swam the 100-meter freestyle in 52.7 seconds at the 2016 Rio Olympics, she did more than just become the first African-American woman to win an individual gold medal in history. She exemplified what it meant to deconstruct cultural barriers: the disparity of African-American girls in competitive swimming.

According to USA Swimming, 64.2 percent of African Americans said they had no swimming ability or very limited ability, drawing connections to the racial inequalities prior to the Civil Rights movement.

“It has to go back to segregation,” girls swim coach Adrienne Wesley said. “Blacks were not able to learn how to swim; that was a privilege that was taken away, so I think that the connection for water and not having access to good public pools [perpetuates it].”

Disparities in the sport extend beyond the swimming pool’s murky history. Swimming is an expensive sport; from caps to suits, which can cost anywhere from $60-150, to the costs of pool memberships and lessons (and in areas without affordable fitness centers, like the YMCA, costs get even higher). However, despite the hurdles of access and affordability, many coaches and swimmers notice an unsung barrier for African-American girls: hair.

“It’s a huge factor,” said Melissa Wilborn, head coach at DeKalb Aquatics. “One of the things that people have tried to do is create swim caps that keep the hair dry; well, that doesn’t work. You find that a lot of the kids will step out of the sport for those reasons.”

Pools can have significant impacts on swimmers’ hair.

“Sometimes the chemicals in the pool mess with the chemicals in the hair,” Wesley said. “Braids can be too heavy; caps aren’t usually big enough. Large-sized caps are relatively new. It’s hard.”

Wesley finds that a lot of people are unaware of just how much time, money and effort goes into hair, and how much of a hindering factor it can be.

“For me to go home at the end of the night, wash my hair, twist my hair and prepare it for the next day is like a two-hour gap,” Wesley said.

While access to pools, cost and the disparities caused by segregation act as the main barriers to the sport, many people find a lack of awareness about the topic of hair.

“I think that people don’t think about it because it may not directly relate to them,” Wilborn said. “I don’t think people think about something that affects someone else until it’s either put in their forefront and it becomes an issue, or they’re living it.”

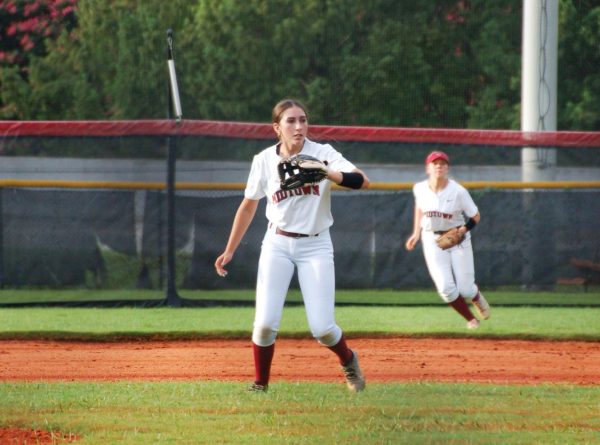

Coaches and swimmers find that representation within swim teams also leads to significant barriers in swimming.

“Swimming head coaches are predominantly caucasian males, so they don’t have an issue with their hair,” said Wilborn, who is African American. “They are not going to think of why this little African-American girl won’t stay in the sport of swimming.”

Issues of representation also exist on a larger scale.

“Growing up, thinking of sports you want to do, swimming is not really one of the sports black people think of first,” said junior Assata Nkosi, who swam with YMCA swimming programs when she was younger. “When you don’t see role models in the sport, it makes you feel worse about being in it. It’s harder to feel encouraged doing the sport.”

However, after the 2016 Rio Olympics, the narrative began to change.

“The first thing people said [about Simone Manuel] is ‘Oh, her hair,’” Wesley said. “Every time she got out, her hair was still slicked down, and I think people were like ‘Ok, you know she didn’t look bad after she got out of the water.’ And she didn’t. I think it gave a face that young girls could see.”

Wesley noticed swimmers seemed to be impacted by Manuel on her own team.

“We had one girl come to Grady and say that she wanted to swim like that,” Wilborn said. “I talk to her about what to do for her hair and how to prepare for swim meets, how to prepare for swim practice and all those things.”

Wilborn, also the head coach at nearby Paideia, observed a similar theme on her team.

“Even at Paideia, which is predominantly caucasian, I think that I’ve had more girls come out for the team because of me being a head coach there than they would have if I hadn’t been there,” said Wilborn. “It’s a comfort level.”

Despite disparities, athletes and coaches are working for progress on the issues of swimming.

“I just received a grant from ESPN Women’s Foundation where we can get minority swimmers back into the sport, and I was able to get several girls back into the sport and try to educate them on hair,” Wilborn said. “It remains an issue, especially when they are older. When they are younger they really don’t care, but when they get older, that’s when it becomes more of an issue.”

Wesley is working to address unsung problems in the sport.

“I have a blog I’m going to launch … called Swim Pretty and that blog is basically focusing on ways to stay pretty while still swimming, so like telling people about different hair products, certain things to do for your hair, how to prepare your hair for swimming,” Wesley said. “Just little things, so people won’t feel like hair is such a major issue and prevent them from actual swimming.”

In many cases, representation is one of the key factors.

“People can see someone they identify with,” Wesley said. “Equivalent to Barack Obama being president, most black people didn’t think they even had a chance to be in such a high office as that. The same happened with Simone. She is someone we can look at and identify with. When you find out her back story, it’s even more identifiable. It makes it more realistic and more tangible.”

The hope is that barriers can be overcome within the African-American community.

“I hope that people will be more opened minded,” Wesley said. “And I mean black people as well. They’re shocked when I say that I coach swimming, and there are so many questions, it’s like I’ve come from another planet.”

Swimmers and coaches agree that education on the topic of hair is one of the most significant ways to overcome the boundary.

“I think education is the critical part, educating people on what products to use, how to use it, when to use it, and then you can continue to be a successful swimmer,” Wilborn said. “You have to educate the people at the top, you have to educate the people in the middle, you have to have people that look like them or people that are conscious of what’s going on in the community to make that better.”

Tyler Jones is a senior in her fourth year writing for the Southerner. When she is not writing features on anything Atlanta, you can usually find her in...