Antisemitism remains prevalent in Atlanta

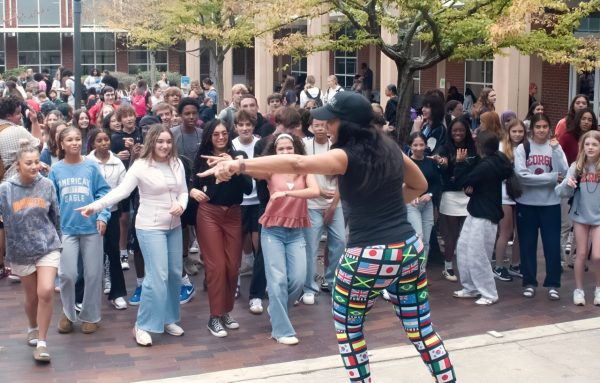

The main sanctuary of Congregation Shearith Israel in Virginia-Highland.

Robert Bowers, a 46-year-old man, walked into the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, PA, and opened fire into the weekly service. By the time Bowers was in custody, 11 people were killed and six were left injured.

In metropolitan Atlanta, there are approximately 40 synagogues and over 120,000 Jews. At Grady, there is a modest Jewish community ranging in levels of faith. This act of hate affected the entire community.

“I was more on edge and aware of everyone in the synagogue,” junior Mia Prausnitz-Weinbaum said after the attack this fall. “It was weird to have to think about that at synagogue.”

Anti-semitism, hostility or prejudice against Jews, is on the rise. According to the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), anti-semitic incidents rose by 57 percent in the United States this year. These incidents include anything from bomb threats to anti-semitic posters.

“It’s just like how my views about going to school changed after Parkland,” junior Amelia Kushner said. “It’s definitely going to be a bit scary when I go back for the first time. I feel like once something like this has happened, it may inspire others to copy it. It’s a scary thought that my congregation or any other could be targeted.”

Georgia has seen one of the largest jumps in anti-semitic acts with an increase of 262 percent, according to the ADL. Atlanta is no stranger to anti-semitism. On Oct. 12, 1958, the Temple, a reform synagogue, was bombed in an attack by anti-semites. Georgia is also known for its false lynching of Jew Leo Frank in 1915.

This hatred still exists in Atlanta today — even at the high school level. In April, five students from Milton High School in Milton, Ga, were arrested for vandalizing a Jewish student’s driveway with anti-semitic messages.

These students were charged with trespassing and vandalizing, as Georgia is one of five states without hate crime laws, despite the fact there are five neo-nazi groups reported in Georgia, according to the Southern Poverty and Law Center. In the United States, Georgia has the fourth highest amount of hate groups with a total of 40, a number which continues to grow.

“We’re living in a time where people’s loneliness and isolation can lead to extremist ideas,” said Rabbi Ari Kaiman, the rabbi at Shearith Israel in Virginia-Highland. “Our awareness that there are real people that hate us for being who we are should never be absent from our conscience.”

Shearith Israel, a conservative congregation, was founded in 1904. The congregation includes over 350 families and continues to expand. Its educational building, once the home of the Ku-Klux-Klan, now has classes for the bi-weekly religious school.

“We always have an armed security guard every Wednesday and Saturday, or at an event with more than 15 people,” said Nancy Gorod, director of the educational program at Sherith Israel. “I sense the presence of them [the security guards] more now.”

There are no standards for security in synagogues in the United States. Jewish homes of worship are responsible for hiring security, the cost of which is covered by a grant from the Department of Homeland Security for up to $10,000 per year. This grant does not cover the full paycheck for security personnel, resulting in the money mostly being spent on hardware like cameras or fences.

“When something like this happens you always have a heightened sense of awareness,” said Lieutenant Dawn Brown, the security guard at Shearith Israel. “You need to make sure you are not complacent. Make sure you’re going through the proper steps to tactically respond if need be.”

In other countries, synagogues hire private security and local police to protect their homes of worship.

“I think security is important in synagogues, but how we do security in synagogues is important too,” said Kaiman. “We strive to be welcoming first. There are people in the world that hate us, and there are not many, but they exist.”

Though many in the Jewish community fear the possibility of a similar attack at their local synagogue, these times are also bringing the community together.

“This Shabbat I expect our sanctuary to be overflowing,” Kaiman said of a recent upcoming service. “This Shabbat, people will show up. They know there is no way a person’s violence can scare us from our commitment to our identity.”

Bram Mansbach is a senior and the sports section editor for the Southerner. When he is not working on pages he is across the street in Piedmont Park as...