Gentrification shifts demographics

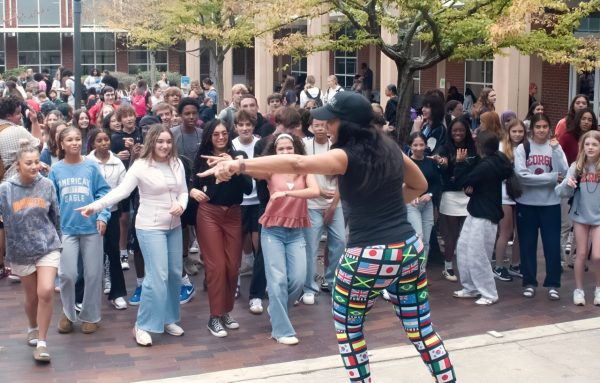

The recent phenomenon of Gentrification sweeping through Atlanta has caused a demographics shift unseen at Grady High School in decades.

In major cities such as New York, Los Angeles and Atlanta, the influx of wealth and development into historically-impoverished communities continues to force out thousands of lower income, primarily minority citizens.

Centered in Midtown Atlanta, Grady’s community is no exception. Gentrification, the process of transforming formerly economically-depressed areas into middle and upper middle class communities, has impacted Grady to such an extent that for the first time since the 1970s, black students are no longer a majority.

“It’s been dramatic,” said Mario Herrera, chair of Grady’s school governance “GO Team” and AP Seminar teacher. “Gentrification and just a booming economy have really changed the school’s demographic.”

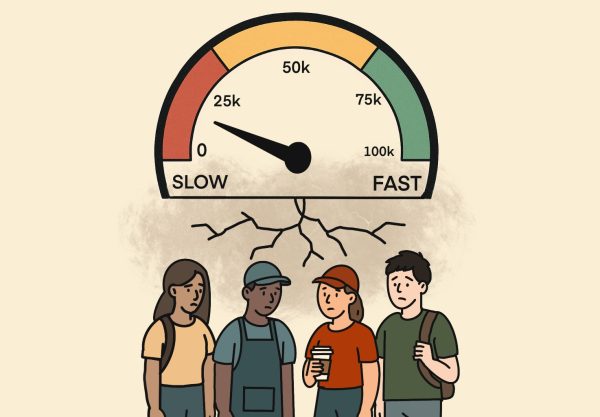

In 2009, Grady’s population included 977 black students, 367 white students and much smaller numbers of Asian and Hispanic students. Now, almost 10 years later, it includes 576 African-American students and 591 caucasian students along with a growing Hispanic population, as those with Hispanic ethnicities account for 8 percent of the student body according to Atlanta Public Schools demographics information.

Gentrification hasn’t been the only cause of this rapid shift. Two important district-made decisions helped influence the pool of Grady students. These were abolishing the communications magnet program and the APS’s rezoning.

“We used to pull from King Middle and now, of course, we are purely Inman,” school business manager Byron Barnes said. “Also, in the time that I have been here, we have phased out the magnet program, which allowed students from other parts of the district to attend Grady.”

Grady’s magnet program started in 1981 as the School of Communications and lasted until 2011 when the Gates Foundation donated money to open small learning communities. As the communications magnet for all of APS, Grady drew students from all over the district, which increased the school’s diversity.

“When the magnet ended, that seriously changed the socioeconomic demographics,” said AP Literature and Composition teacher Lisa Willoughby, who has taught at Grady for 34 years. “At that time, the magnet brought in students from all over the school system. We got students from all kinds of elementary schools, which brought in a lot of middle class African-American students.”

Because the magnet program drew from such extensive areas, it allowed for Grady to hold true to its motto of “Individually we are different, Together we are Grady” than it does today with clearer divisions in the student body.

“Part of the split that exists at Grady now exists because kids who are poor are largely African-American and the kids who are affluent are largely European-American, for the most part,” Willoughby said. “This means that the division is both class and race which exacerbated a lot of the divisions today and that didn’t exist when the magnet program was here because it brought in middle class African-American kids who helped blend the school.”

The trend of ethnic breakup, which started with rezoning and the termination of the magnet program, continues to be fueled by persisting gentrification and shows no sign of slowing down. The freshman class is the largest class in history at Grady and only 36 percent of this class are African-American an immense difference from prior years. This majority may seem like a small increment but Inman Middle is Grady’s sole feeder and has a 53.3 percent caucasian majority which will influence Grady in the future.

“I think people are going to continue to be priced out of living in Midtown,Virginia-Highland and Morningside,” said Herrera. “I think with the old Howard High School now becoming Howard Middle and Inman going over there, that gentrification of the Old 4th Ward is just going to continue to outpace itself and we will probably see that gentrification further impact our demography here at Grady.”

It isn’t just administrators and faculty that have noticed the demographics shifts in Grady over the past several years. Students have noticed, too, and they worry about how it will affect their school’s identity.

“The true shame in the changing demographics of Grady isn’t necessarily how the school looks from the outside,” said senior Harrison Gray. “This change which represents the issue of Gentrification poses the biggest threat to who Grady is.”

George is in his fourth year of the journalism pathway and has been a Southerner editor for three years now. Along with spending long hours at late nights,...

O4W Resident • Dec 29, 2019 at 9:03 am

The gentrification and demographic shift will eventually come to a stop.

1) The prices for many of the new homes in O4W are in the millions which is ridiculous. They are so overpriced for a number of reasons.

2) These gentrified areas are still mostly under black political control and that scares away many white gentrifiers that are leading the Atlanta demographic shift. Also it’s important to mention that whites are the slowest growing demographic in metro ATL just like it is in most major cities.

3) Many people who can purchase expensive homes prefer their children enroll in elite private schools. I know that admissions into these schools are competitive but I feel like that’s their first choice over Grady. Even if the educational value is about the same, with the upper middle class and 1%-ers a private school education is a heralded status symbol. Also I’m sure they prefer their children socialize with MOSTLY children that share their privilage which they won’t find at Grady. Grady will always have a large population of kids from economic disadvantaged backgrounds … which in my opinion make them more cool and interesting than those practically given everything on a silver platter but won’t get into that

4) There are many initiatives to stop gentrification in Atlanta. It has gotten so bad that even white people are complaining about it. For example, several white owned gay bars in Midtown have been shut down or been threatened to be shut down b/c of gentrification. White people are the highest earning group in Atlanta but that doesn’t mean most can afford to keep up with the crazy gentrification going on in so many area. These soulless corporate white gentrifiers are greedy individuals who will sell their own children if it will lead to an amazing profit … they don’t care about the well-being of ATL and will erase its rich history, culture, trees etc without blinking an eye.