Medical innovators ease life for patients with disabilities

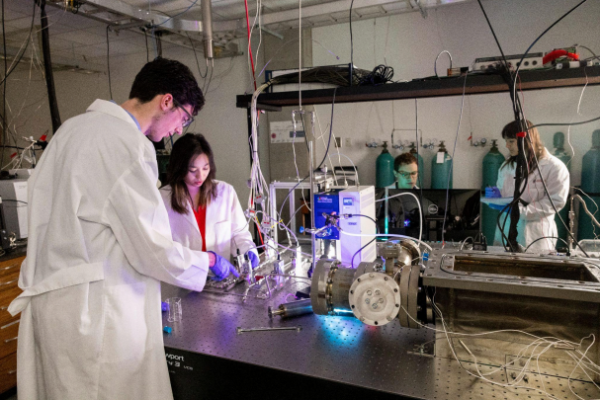

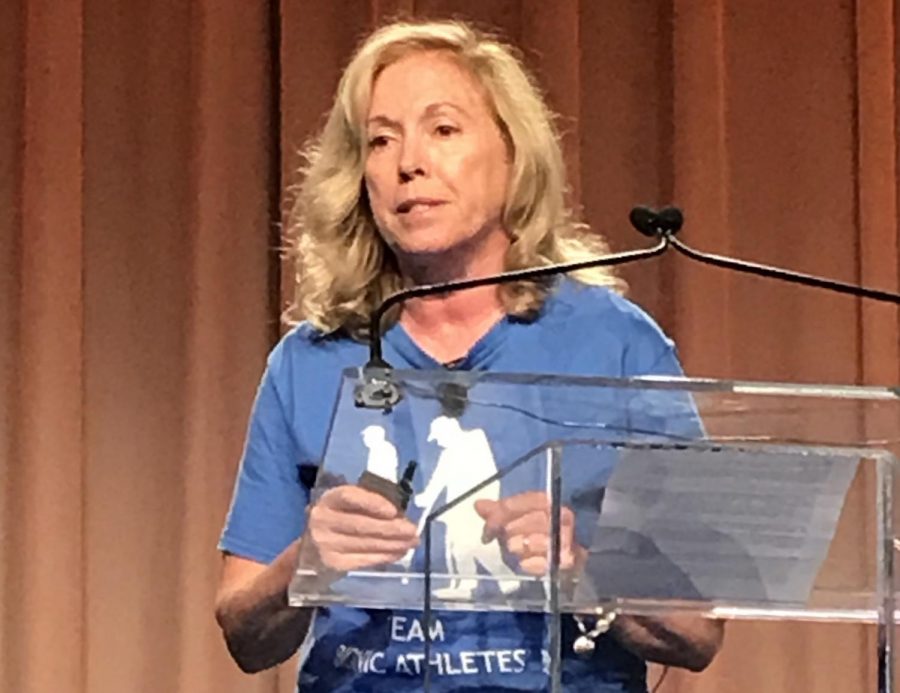

Dr. Ann Spungen, a spinal cord researcher at Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai University, speaks at a panel discussion about exoskeleton, robotic technology for paralysis patients at the No Barriers Summit in New York City on Oct. 5, 2018.

NEW YORK

Medical innovators presented their work on technological advances for people with physical disabilities at the No Barriers Summit in New York City in early October to expand their reach and inspire others to make advances in bioengineering.

Researchers shared the latest technologies in supportive exoskeletons for patients paralyzed as a result of spinal cord injuries, as well as functional 3D-printed prosthetics and other mobility aids. Five Grady students attended the summit, as the national high school winner, to present their winning project. The team created sensory-friendly events for kids with sensory processing disorder and their families. They won $5,000 and the opportunity to present to students and teachers at the global summit.

Most people think of bugs when they hear the word “exoskeleton,” but to Dr. Ann Spungen, they’re life-changing medical devices. These supportive metal frames make it possible for a select few patients with paralysis from the waist down to walk.

“Believe it or not, 50 percent of the population gets excluded solely due to bone density, because people with spinal cord injuries can lose as much as 40 to 69 percent of their bone mass within two years of injury,” Dr. Spungen, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai University, told summit attendees at the Intrepid Air, Sea & Space Museum on the Hudson River in lower Manhattan.

In spite of restrictions, exoskeletons are life-changing for those who qualify to use them, she said. Architect Robert Wu was paralyzed from the waist down in 2007 and was one of Dr. Spungen’s patients, who joined her to speak at the summit.

“Life was very devastating for me at the time,” said Wu. “But three years later, I was able to stand and walk using the exoskeleton … there’s just so much more I can do like this.”

Exoskeletons weren’t the only technologies presented at the No Barriers Life Panel. Jen Owen, co-founder of enablingthefuture.org, presented the 3D-printed prosthetic that led to an influx of free online prosthetic hand designs. She says it all began with a cosplay.

“My husband and I decided to go to a Steampunk convention,” said Owen. “And for his costume, he made this giant metal hand that actually functioned when he moved his fingers.”

Jen and her husband Ivan posted a video of the working hand on Facebook and forgot about it until four months later, when a carpenter from South Africa contacted them. He had lost four fingers in an accident. He wanted to work with Ivan Owen to design replacement fingers, because a prosthetic would have cost him roughly $10,000.

“They literally had to work together on Skype and email,” said Owen. “I don’t know if you’ve ever tried designing something for somebody without them there, but it doesn’t work very well.”

In the beginning, distance and cost forced Ivan Owen and the carpenter to get creative with supplies for their prototype prosthetic.

“Their first prototypes consisted of toilet paper tubes, rivets, leather, lots and lots of duct tape,” said Owen. “And after awhile, they starting stealing toys from the kids’ toy box and come up with a functioning prototype that could actually pick things up.”

Over time, more people contacted Owen with requests for prosthetics. To make design possible from a distance and accommodate the growing number of children who would soon outgrow their prosthetics, Owen began to collaborate with families using 3D printing.

After a video of Liam, a boy for whom Ivan Owen designed a prosthetic, went viral, people across the globe engaged in the project. Some offered to print the prosthetics with their 3D printers, others designed more prototypes, and families continued requesting prosthetics.

“I decided to take the original blog I had and turn it into a new one for a new kind of story,” said Owen. “I made it so I could share the stories that were coming in, and also media could find it.”

People began sending measurements of their kids’ hands to volunteers, and the project continues today. From their start at a cosplay convention, the Owens have turned one Steampunk hand into a global organization called E-Nable. While the hands aren’t as developed as more expensive prosthetics, they meet the needs of thousands.

“Things that we take for granted, these kids are excited about,” said Owen. “They want to hold onto their bike handles. They want to jump rope … it’s not really the function of the hand, it’s that they now feel like superheroes themselves.”