Genetic tests reveal students’ DNA information

Students can buy kits from a variety of websites that allow them to test their DNA.

Less than 20 years ago, the human genome was fully sequenced for the first time in history. Now, in 2018, scientists have made so much progress in the field of genetics that for $99, practically anyone can have their DNA analyzed.

Services such as 23andMe, Ancestry, and MyHeritage offer “direct-to-consumer” genetic tests where users send in saliva samples and then, after six to eight weeks, receive a detailed report about their genetics. These services, which several Grady students have used, give users insight about the countries and ethnic groups their ancestors came from.

“Since I’m adopted, I never knew anything about my biological parents or biological family,” sophomore Tomas Bockman, son of Principal Dr. Betsy Bockman, said. “I wanted to learn at least what my ethnicity was.”

Like Bockman, junior Haley Henderson was curious about her ethnicity because she has never met her biological father.

“[My father] is Colombian, and my mother is white, so I wanted to know how that genetic breakdown worked and how much of my ancestry was what,” Henderson said.

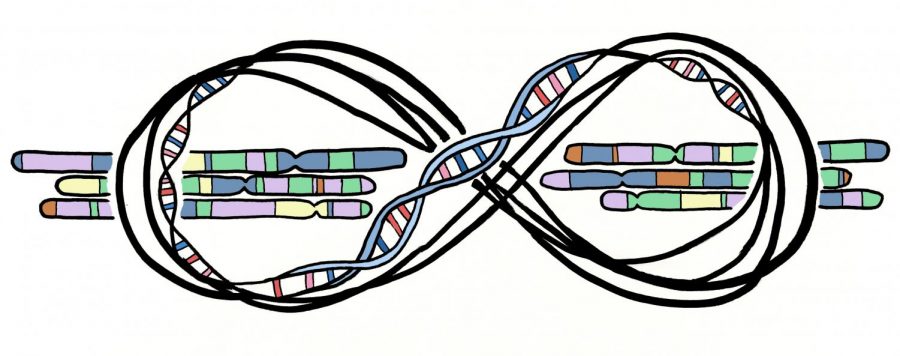

Genetic tests use single-nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs, to examine relationships between genes. SNPs are variations of a single genetic “letter” in the genome. They are passed from generation to generation, so each region studied in genetic tests has some SNPs that are more common in that ancestral population. Genealogy tests work by finding SNPs in specific locations on the genome to determine which populations the user descends from.

For some people, these tests can have a significant impact on their lives. Liza Crenshaw, communications manager at 23andMe, often hears stories like this from users. For example, a gene variant on chromosome number 13, known as BRCA2 has been shown to highly increase the risk of a person developing breast cancer.

“I talked to a customer recently who found she had the BRCA2 variant and, after undergoing confirmatory testing with her doctor, is now having a double mastectomy to reduce her risk of getting breast cancer,” Crenshaw said. “On the ancestry side, we frequently hear from customers who have found or been re-connected with family members.”

As it turns out, unexpected results are quite common. Junior Maddie Thorpe received a 23andMe kit as a Christmas gift, and her mother has tested herself as well.

“There’s this whole family legend that [my mom’s] great-great-grandmother was Native American, and when she took the test, there was nothing,” Thorpe said. “She was 100 percent European.”

Henderson’s results surprised her, too. She was 48 percent European and 40 percent native South American.

“I had no Spanish DNA, which meant that my ancestors somehow got through the Spanish showing up… without being affected,” Henderson said.

According to Crenshaw, the mission of 23andMe is “to help people access, understand and benefit from the human genome,” and at Grady, this mission is already underway. Genetic tests can reveal information about people’s background they would otherwise have no way of knowing, which students have personally experienced.

“I always felt vaguely nonwhite in my identity,” Henderson said. “Getting that test, it was interesting to realize how my racial breakdown actually works.”