Anyone who observed an APS school in late April and early May might have noticed something unusual: empty hallways, patrolling administrators and thousands of focused students filling in small bubbles on mass-produced answering documents. Across APS, April 23 to May 13 is the three-week period designated for students to stop learning, for teachers to stop teaching, and for standardized tests to be administered to measure student progress.

Anyone who observed an APS school in late April and early May might have noticed something unusual: empty hallways, patrolling administrators and thousands of focused students filling in small bubbles on mass-produced answering documents. Across APS, April 23 to May 13 is the three-week period designated for students to stop learning, for teachers to stop teaching, and for standardized tests to be administered to measure student progress.

Although APS has administered the Criterion-Referenced Competency Tests to third- through eighth-graders and the End of Course Tests to high schoolers since 2000, this year’s testing period was different. A month removed from the indictment of former Superintendent Beverly Hall, as well as 34 other APS educators, and two years removed from the investigation that found that 44 out of the 56 APS schools in the district had cheated on the CRCT, the implementation of the tests faced heightened scrutiny.

From Hall to Davis

One of Beverly Hall’s defining characteristics during her tenure as APS superintendent was her demand for improved test scores, with the threat of unemployment looming for those principals and administrators who failed to meet performance targets. In fact, according to The New York Times, during the 11 years of her tenure, 90 percent of APS principals were replaced.

During this time, Grady largely avoided major changes in testing protocol. AP World History and AP Comparative Government and Politics teacher James Campbell said that, over the course of his six years at Grady, he has noticed differences in testing procedures, but not in the testing environment.

“The test procedures have become a lot more formalized,” Campbell said. “In terms of standardized test pressure, I have never felt that here.”

Russell Plasczyk, Law and Leadership Academy leader, said the biggest change in testing procedures has been that the security of the administration of all tests is now a top priority.

“Everything now has to be locked up,” Plasczyk said.

According to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, APS has created double-locked “safe rooms,” accessible only by principals and testing coordinators, and monitored by video surveillance, to store test materials in every school.

Furthermore, according to an editorial by Superintendent Erroll Davis in The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, APS has “set trigger points that will result in automatic investigations of schools where test scores show larger-than-normal year-over-year changes.”

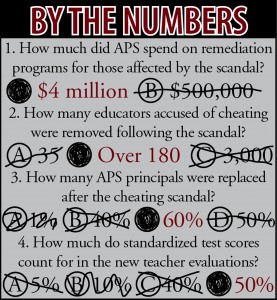

Other ways APS has tried to get back on track since the cheating scandal are remediation programs for those directly affected by the scandal, which have cost $4 million so far, according to the Associated Press, as well as mandatory ethics training for all APS employees. Furthermore, according to the Associated Press, every APS school now has an “ethics advocate” to help employees resolve ethical issues.

In a letter released to APS students, parents, employees, and partners released the day of the indictment of 35 APS educators, Davis said APS is “ready to put this troubling episode behind us.”

In the letter, Davis writes, “Over the past two years, we have taken action to renew our organization’s collective commitment to students, parents, employees, partners and community members. From requiring all employees to complete annual ethics training as a condition of employment to strengthening safeguards on test materials, we have done considerable work both to prevent and to punish cheating,” the letter said.

Teacher Keys=key to success?

Georgia was granted $400 million from Race to the Top, President Obama’s education initiative, to implement a new teacher evaluation system called the Teacher Keys Evaluation System. The system, which is expected to be implemented in every district by the 2014-2015 school year, will be based half on student performance on standardized tests and half on other things, like student surveys and classroom observations.

Business and Entrepreneurship Academy leader Willie Vincent said that, the Race to the Top funds required participating districts to “create some innovative way of assessing teaching and learning.”

“We’re trying to do something cutting edge,” Vincent said.

For the 26 districts, including APS, that have already adopted TKES, that cutting edge idea turned out to be the Student Learning Objectives assessments. The SLO assessments, which were first implemented at Grady and around the state this school year, aim to measure student growth by “value added,” or how much the student has improved throughout the school year, instead of purely by where the student was at the end of the year. The first round of SLO assessments was administered in October 2012, and the second round in March 2013.

State officials insist that standardized test scores should be factored into teacher evaluation. So does the educational reform organization and steadfast supporter of standardized tests StudentsFirst, which argues that the new evaluation system “gives teachers and principals the respect they deserve by recognizing those who are great and providing resources to those who may benefit from extra help.”

Not everyone agrees that the value-added approach is a step in the right direction. A study by Stanford professors Linda Darling-Hammond and Edward Haertel concluded that value-added models of teacher effectiveness, which the SLO assessments use, are flawed because they are “highly unstable,” “significantly affected by differences in the students who are assigned to them,” and “cannot disentangle the many influences on student progress.”

Furthermore, some critics point out that it is apparently very easy to get a positive evaluation under the system. According to the Associated Press, an initial review showed that about 84 percent of teachers in the first year of TKES received a “proficient” or “exemplary” rating.

The implementation of the SLO assessments at Grady also drew some criticism. World geography and American government teacher Susan Salvesen said many students took issue with the wording of certain questions on the World Geography SLO assessment, and the rubric she received to grade the assessments required her to grade as incorrect what should have been a correct answer.

Other teachers didn’t like the fact that they were required to grade the tests themselves.

“I think teachers are incredibly uncomfortable with being asked to grade a test that will then be a basis for their evaluation,” AP English Language and Composition teacher Lisa Willoughby said.

Vincent, however, is confident that the creators of the SLO assessments are “still working out the bugs.”

AP U.S. History teacher Lee Pope expanded on that sentiment, saying he doesn’t think that “right now is the time to overreact.”

Pope added that, in his seven years at Grady, he has observed that some policy changes are just ephemeral fads that are like “flavor of the week,” being implemented, and then, just as quickly, abandoned.

Educational reform: quid pro quo?

The massive cheating scandal, though it didn’t directly affect Grady, sparked a national debate about the use of high-stakes standardized testing. Some argued that these tests force teachers to teach only how to be a good test-taker, rather than challenging students to grapple with complex issues and use critical thinking. Others claimed the tests inherently lead to cheating, as they incentivize higher scores. Some argued, however, that standardized testing can reveal important trends and it was a failure of leadership, not the testing itself, that was to blame for the APS cheating scandal.

Two major educational initiatives, former President George W. Bush’s No Child Left Behind and President Obama’s Race to the Top, embraced standardized testing as a tool to measure student and teacher performance. As a result of these programs, Georgia schools were pressured to increase their CRCT scores, and faced sanctions if they failed to do so.

Some, however, complained that this educational reform movement seemed to be motivated by corporate interests, and it disproportionately hurt poor and minority students. Many more protested NCLB’s requirements, arguing that its goals, including 100 percent proficiency in math and science by 2014, were unrealistic and impossible to meet.

Some even claimed that these high goals were what led some Atlanta educators to change their students’ answers on the CRCT during the cheating scandal. Walt Haney, a professor of education at Boston College, told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2011 that, as the stakes for standardized testing increased, cheating grew more prevalent.

“It’s this idiotic pressure on schools and teachers regarding test results that I think is corrupting not just the test results, but education,” Haney said.

Willoughby agrees.

“I think that when you have monetary incentives attached to student achievement on tests that that incentivizes cheating and there’s a ton of empirical examples that that’s true,” Willoughby said.

President Obama’s Secretary of Education, Arne Duncan acknowledged that the Atlanta cheating scandal was disturbing, but insisted that standardized testing was not the cause of it.

“Lots of places are seeing tremendous reform, are moving forward, doing great and doing it the right way,” Duncan told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “The saddest thing here is the Atlanta public schools were making real progress. And now that’s buried in this story.”

Even so, in response to the protest, NCLB is currently undergoing revisions to deemphasize the harsh sanctions. In February 2012, Georgia and several other states were granted a waiver from certain NCLB requirements in return for agreeing to “raise standards, improve accountability, and undertake essential reforms to improve teacher effectiveness,” according to a White House statement.

Which came first: the test or the cheating?

Many journalists and education advocates, from David Brooks to Bill Gates, have come out against the use of high-stakes standardized testing since news of the APS cheating scandal first broke in 2009.

“It is time to acknowledge that the fashionable theory of school reform — requiring that pay and job security for teachers, principals and administrators depend on their students’ standardized test scores — is at best a well-intentioned mistake, and at worst nothing but a racket,” Eugune Robinson wrote in an op-ed for the Washington Post, referencing the racketeering charges brought against 35 APS educators in the March 29 indictment.

“The association between performance on these tests and teaching and/or learning behaviors is problematic,” Edmund Gordon, the John M. Musser Professor of Psychology at Yale University, wrote in an op-ed published on April 15. “There is little evidence that such use of test data influences student achievement.”

Campbell also disagrees with the increased use of standardized testing.

“I suppose there is inherently a flaw with asking any teacher or any student to be judged by one single day,” Campbell said.

Pope, however, thinks standardized tests are valuable because they reveal information about students’ knowledge and his teaching abilities.

“I think testing is important to judge the knowledge of a child,” Pope said. “I think that it is important to judge my ability as a teacher.”

Pope said that because of standardized test scores, he knows that he becomes “a less effective teacher by the fourth hour, by the third time I teach that class in a day.”

Michael J. Feuer, professor of education policy and the dean of the graduate school of education and human development at the George Washington University, also said standardized testing can be useful, arguing that educational policies that favor high-stakes testing shouldn’t take the blame for the APS cheating scandal.

“Tests can help gauge individual learning, give teachers additional information about their students’ progress, provide objective indicators of student achievement and expose inequalities in the allocation of educational resources,” Feuer wrote in an op-ed for Education Week.

Although the cheating scandal is now in the rearview mirror of APS (if not the 35 educators who were indicted), the question of the role of standardized testing in schools remains at the forefront. Although Campbell is willing to “accept the idea that a good test exists,” he said the way they are implemented now is problematic.

“The tests we have now are flawed,” Campbell said. “Perhaps all tests are flawed, but these are flawed in a way that not all tests are flawed.”